November 1, 2020The disappearance of birdsong is surely one of the most poignant signifiers of our fragile planet’s environmental peril. “Birdsongs are a backdrop to daily life,” writes the celebrated sculptor Elizabeth Turk in a catalogue essay for the exhibition “Tipping Point: Echoes of Extinction,” at Manhattan’s Hirschl & Adler Modern gallery.

Turk, best known until now for her intricate hand-carved marble sculptures, began brainstorming the ambitious project several years ago, as recurring wildfires in her native California decimated bird populations.

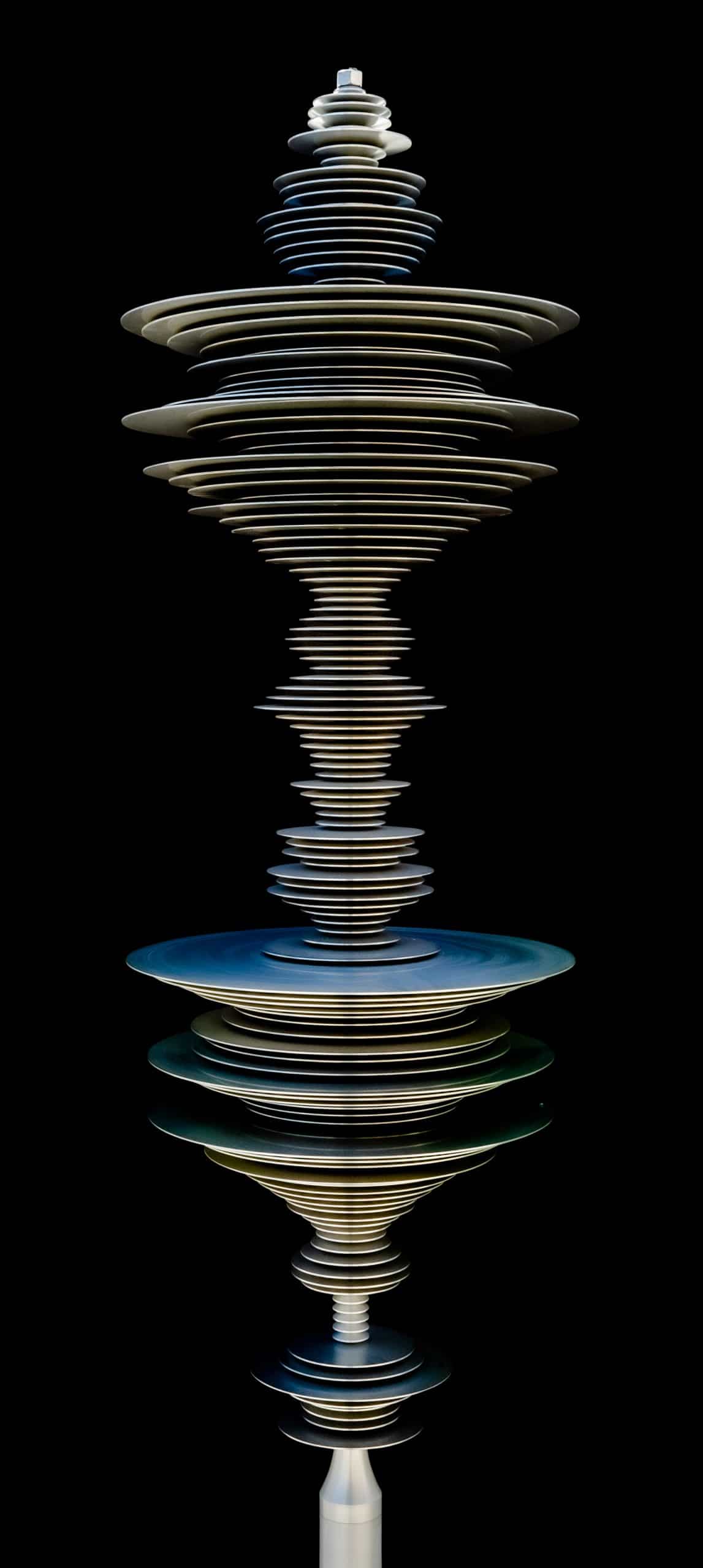

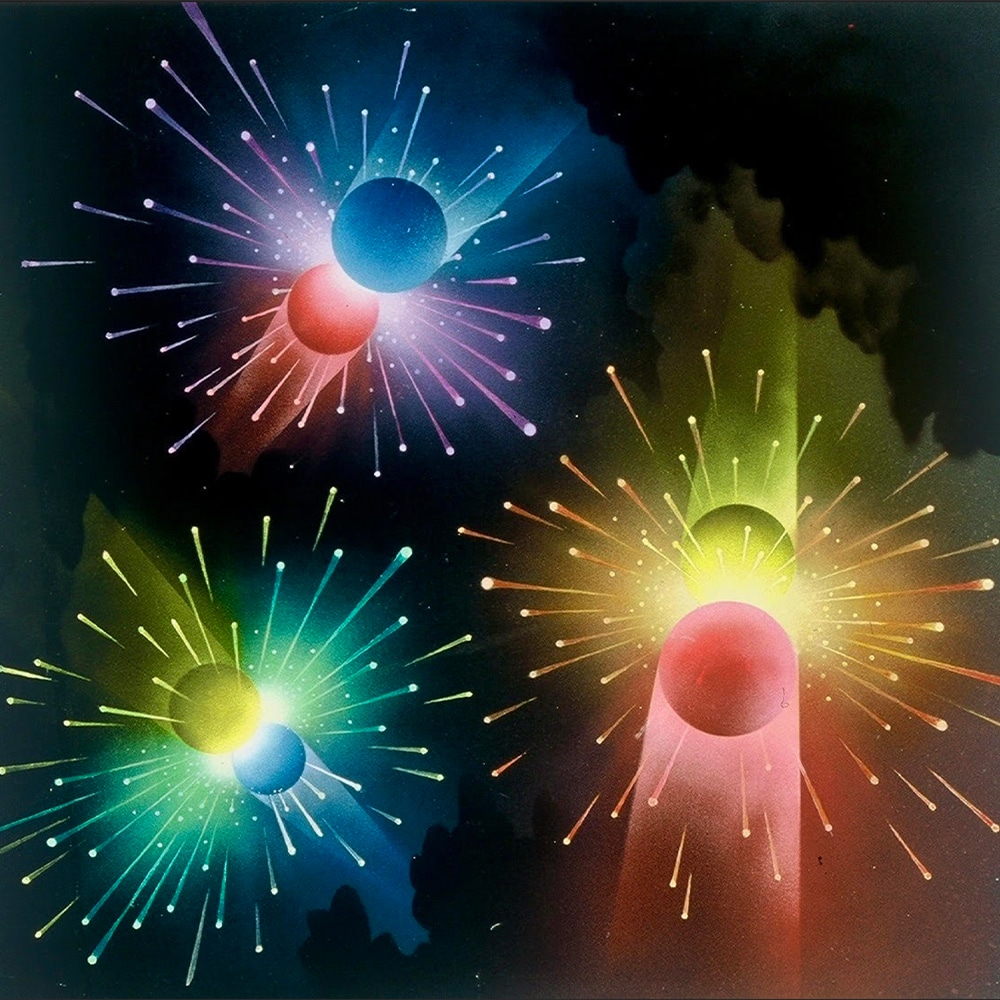

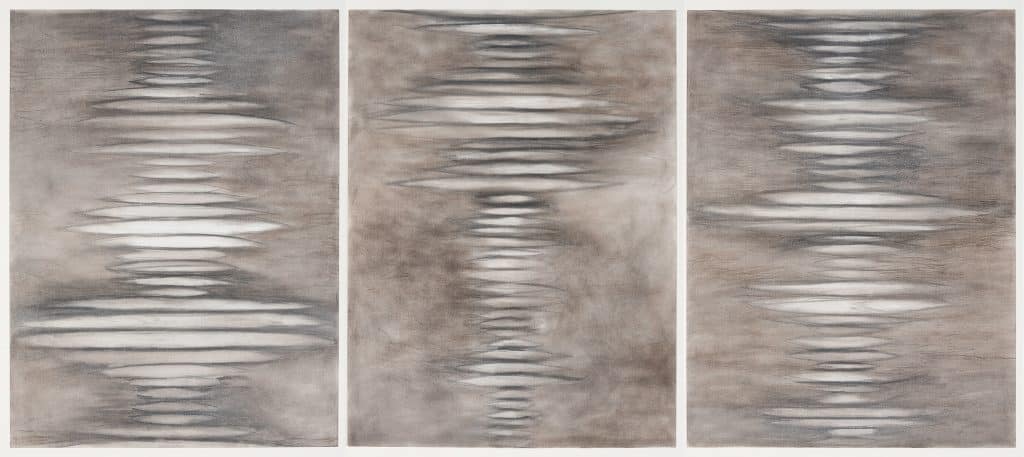

“Tipping Point” comprises 27 totemic Sound Columns — elegant sculptural visualizations of the lost voices of endangered and extinct birds like the ivory-billed woodpecker and hyacinth macaw, as well as such sea mammals as the sei whale and vaquita porpoise — along with a number of related drawings made from the ash and charcoal of forest fires. The concept is poetic and the installation startlingly beautiful, heartbreaking yet not without hope.

“The exhibit opens with the bald eagle. It’s a suspended piece in the very center of the first room and kind of leads the way,” Turk says. Although many of the works are attached to more sobering outcomes, “the bald eagle is an optimistic story,” she says. “In Southern California, they were almost eradicated, but with effort they brought it back. So the tipping point can go in both directions.”

The towering forest of vertical forms, many on pedestals and some more than eight feet high, are dramatically arrayed and spot-lit in Hirschl & Adler Modern’s ninth floor gallery at 41 East 57th Street. Their kinetic shapes — many of them vibrate gently — were derived from printouts of sound waves representing vanished and vanishing creatures’ calls.

Working with recordings archived by the Macaulay Library of the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Turk upended and enlarged the sound-wave images and painstakingly reproduced the resulting shapes in a variety of materials, from wood and bronze to anodized aluminum and 3-D-printed plastic.

“It’s really a very simple idea,” the sculptor says. “I’m trying to give an absence — the huge number of extinctions in the natural world — physical form, fleshing out a conversation around extinction and using art as a vehicle.”

The aural component of the exhibition is key to its emotional impact. Turk wants the installation to hit viewers “like a bomb exploding, not like a narrative.” Each piece is accompanied by a scannable QR code, allowing gallerygoers to access a recording of a lost or endangered creature’s voice. Those viewing the show remotely can access the same recordings via the exhibition catalogue on the Hirshl & Adler website, which opens in the ISSUU reader; the exhibition checklist, on pages 14 through 15, contains live links that take the viewer to the relevant birdsongs in the Macaulay Library.

For those animals that went extinct before the advent of sound recording, like the many Amazonian birds lost to the 19th-century fashion for brilliant plumes on women’s millinery, Turk used recordings of living relatives in the same genus.

“Conceptually, it’s similar to how I was approaching marble,” says the artist, who has received high honors for her work in that medium, including a MacArthur “Genius Grant,” an award from the Barnett Newman Foundation and a Smithsonian Artist Research Fellowship. Her swirling, elaborately worked sculptures have been acquired by the Jewish Museum in New York; the National Museum of Women in the Arts, in Washington, D.C.; the Los Angeles County Museum of Art; and the Mint Museum, in Charlotte, North Carolina, among other institutions.

“The aha moment in a lot of the marble pieces is when you realize the emptiness, how much is not there,” Turk explains. “It’s the same here, though I’m constructing positive forms out of absence.”

Turk’s interest in birdsong began in the early 1990s when, needing an “ominous sound” for her final MFA project at the Maryland Institute College of Art, she sought a recording of a mass of starlings and discovered the Cornell Lab as a resource.

She began paying more attention to birdsong in her daily life. “At first, I was thinking how beautiful it was, and how other sounds were overwhelming it,” she says. “But gradually, I realized that birdsongs weren’t just being covered up, but eradicated.”

The show at Hirschl & Adler Modern sprang directly from a 2018 installation at Southern California’s Catalina Island Museum, which included some of Turk’s earliest Sound Columns as well as an event at which attendees were given light-up wands to write in the air the names of things that have gone missing, including birds and birdsong.

“Almost all my work has an environmental edge to it,” Turk says. “Long ago, I jumped into marble to make nature memorials — I was thinking about monuments to nature, to a river or stream or pond. We now think of water as a bottle or a brand. I was reflecting on that change.”

“Tipping Point” (on view through November 20) is the first “live and in-person” show at Hirschl & Adler Modern since it shut down last March because of Covid-19. “We just decided to go ahead and do it,” says Elizabeth Feld, the gallery’s managing director.

“What’s going on in California is worse than expected. Birds are dropping dead every day,” Feld continues. “It may not be the ultimate moment commercially, but it’s the ultimate moment in terms of message.”

Intense protocols are in place for the exhibition, including a full-body thermal scan for all visitors in the lobby of the historic Fuller Building, where the gallery is located; a form to fill out for contact tracing; a limit of six visitors at a time during the gallery’s regular opening hours (individual appointments are available as well); and, of course, proper masking.

Hirschl & Adler Modern, which has represented Turk since 2000, staged her last major show, “Tensions” — featuring works of intricately carved marble combined with wood and stone — in 2015. The gallery staff played no small part in helping to realize her vision for “Tipping Point,” as many of the pieces were shipped from her Santa Ana studio in sections and had to be put together “like adult Lego,” Feld says.

“The bronze sculptures representing bush wrens from New Zealand are smaller tabletop sculptures that were cast as a single piece,” she adds. “But others, like the silver aluminum mammal sculptures, came as boxes of disks with graceful little lips that we threaded onto a strong steel rod. Elizabeth spent two years figuring out the engineering of these works before she even shared the idea. And when she brought it to us, our mouths were on the floor.”

The materials palette for Turk’s new sculptures is wide-ranging. Some are made of natural woods — cherry, for instance, for the brown pelican and walnut for the ivory-billed woodpecker. Many are anodized aluminum, colored light blue, dark blue, gold and green for representations of endangered species — like the North Pacific right whale, banded cotinga and red-browed parrot — or black for extinct ones, like the Jamaican macaw. The Carolina parakeet and bush wren are rendered in 3-D-printed ABS filament coated with a graphene paint that imparts a surface roughness.

Turk tried out varied media because, she says, “I wasn’t sure how the voices of these birds would feel in the different materials. The three-D-printed pieces were the original experiment, because I was doing so much work on the computer. Wood feels like the spaces where the birds lived — that was something I had to explore. The machine-made aluminum pieces played into the conversation because that’s the more abrasive side of the human experience, what comes of not living side by side in an empathetic exchange with nature.”

Turk sees the works in “Tipping Point” as contributing to a necessary conversation about humanity’s place in nature.

“How we came out on top of the pyramid, constantly trying to dominate nature, using it for our selfish purposes, is incomprehensible to me,” she says. “With this show, I’m trying to put us back inside the totality of it all. Environmental issues are so overwhelming that people stick their heads in the sand. But when you play, you come up with solutions. And that’s when change — change that is hopefully positive — starts to happen.”