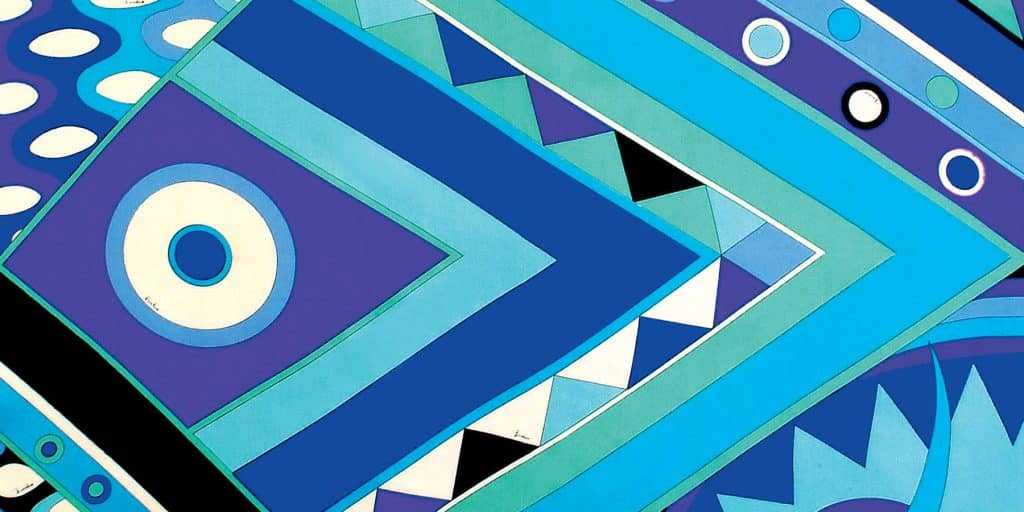

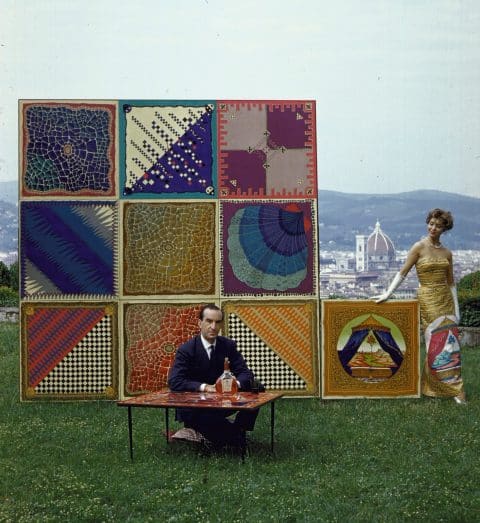

October 6, 2019The Prince of Prints, Emilio Pucci expanded his fashion business into a lifestyle powerhouse, as detailed in the new book Unexpected Pucci (Rizzoli). In this 1959 photo, the designer sits on the lawn of his palazzo in front of a display of scarves from his 1957 Patio and 1959 Botticelliana collections. The model is wearing a dress adorned with the Padiglione motif (photo by David Lees/The LIFE Images Collection via Getty Images/Getty Images). Top: Detail of a scarf in the Vivara pattern, which was introduced in 1965 and has become emblematic of the Pucci lifestyle. Photo courtesy Emilio Pucci Archive, Florence

My prints are ornamental designs worked in continuous motion; however they are placed, there is rhythm,” Emilio Pucci, once said. This should come as no surprise to sun lovers, for whom a slithery Pucci garment in sensuous psychedelic silk jersey is an imperative when sashaying along the beach after an Aperol spritz or two. But for those of us who are just as happy to remain prone indoors with a stiff martini, the lavishly illustrated Unexpected Pucci: Interiors: Furniture, Ceramics and Art Pieces (Rizzoli) is a welcome eye-opener.

By the mid-1960s, the international fashion press had dubbed the Florentine designer the Prince of Prints. Less well known is that, starting in the early 1950s, Pucci applied his colorful, abstract patterns to static angular mediums such as ceramics, floors and furniture, imbuing them with movement, not to mention glamour. He was the first fashion designer to enter the lifestyle market, founding the successful brand that exists today.

Pucci lithographs, from left: Night Flower, Sensitivity and Mystery of Womanhood, all from 1974, Photos by Lapo Quagli

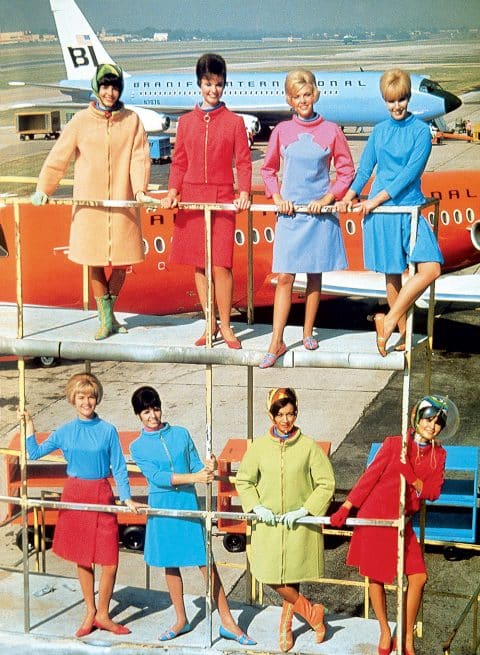

Emilio Pucci designed these hostess uniforms for Braniff Airlines in 1966. Photo by D.R.

Unexpected Pucci is a kaleidoscopic guide to the company’s unique heritage and iconography. It was authored by his daughter Laudomia, who inherited the business at her father’s death in 1992. Today, she is vice president and image director of the company, which is part-owned by LVMH Moët Hennessy Louis Vuitton and now based in Milan, after decades occupying the family’s 13th-century Florentine palazzo.

With an introduction by Suzy Menkes, editor of Vogue International, and pithy contributions from such notables as architect and designer Piero Lissoni and fashion writer Angelo Flaccavento, the book celebrates Pucci’s pioneering artistic journey. Drawing on material from the Pucci archives, it reveals the not-so-well-known partnerships forged with luminaries of art and design that turned the fashion company into a lifestyle brand. From the airline uniforms he created for Braniff in the 1960s to the emblem he crafted for the Apollo XV space mission in 1971, Pucci’s designs were visionary. He was also the first to build an empire without selling out, pointing the way to marketing plans of the future without crafting an actual marketing plan himself.

Left: The bedroom of illustrious design couple Delphine and Reed Krakoff’s daughter Maude features a Pucci rug in the Occhi motif. Photo by Sheila Metzner/Trunk Archive. Right: A 2014 partnership between Emilio Pucci and Kartell resulted in Philippe Starck’s Madame chair, shown here upholstered in Shanghai and Avenue Montaigne prints from the Cities of the World collection. Photo by Lapo Quagli

Yacht maker Wally’s 2003 18-meter Wallyño featured a hand-painted Vivara-print sail. Photo by Carlo Borlenghi

Born in 1914 to one of Italy’s oldest families (the Borgias were their enemies), Emilio Pucci, Marchese Pucci di Barsento, was a member of the postwar international jet set, hopping from beach to mountain to city. His fashion career began unexpectedly in 1947, when he created a revolutionary stretch ski outfit that was photographed on the Swiss slopes for Harper’s Bazaar. Eschewing a life of aristocratic glamour, the self-taught designer opened a boutique on Capri dedicated to simple resort clothing (think capri pants) that evoked the Mediterranean’s undulating waves and refreshingly bright colors. At the time, luxury fashion was as constricted as a Dior cocktail dress, but the Swinging Sixties were on the horizon. Signed with what Menkes calls a “handwritten ‘Emilio’ flourish” — a concept, she points out, as novel as that of designer ready-to-wear — his designs were soon seen on celebrities like Jackie Kennedy and Marilyn Monroe.

Left: Emilio Pucci for Rosenthal Studio-Line coffee set in the Quadratini motif, 1961. Photo courtesy Emilio Pucci Archive, Florence. Right: Set of Emilio Pucci for Rosenthal Studio-Line Vivara-motif vases, 1960s. Photo by Thomas Dell’Agnello – Studio Quagli

Model Veruschka with her body painted in a Vivara motif. Photo by Franco Rubertelli/Vogue ©Conde Nast

“My involvement is not just to sniff at the fashions bearing my signature. Designs must be created by me, and that’s what I have done with everything,” Pucci explained in one of his many quotes in the book. His clearly defined aesthetic system enabled him to venture into the “unfamiliar territories” of designer and collector objects, Laudomia writes in her chapter, “Wrapped in a Scarf.” Most of his work began with a new scarf design. Take the Vivara print, from the 1960s. Inspired by the crescent shape of Ischia, an island in the Gulf of Naples, the motif was used for a groundbreaking partnership with luxury German porcelain company Rosenthal. Pucci literally wrapped a Vivera scarf around the hard ceramics while experimenting with scale and curves, ensuring rhythmic flow “like an engineer,” explains Laudomia. Vivara — like such other designs as Emilio, Lamborghini and Ovali — appears as well on towels, pillows and, most recently, a hand-painted sail on a Wally yacht. Vivara is also the name of the first Pucci fragrance, which was launched in 1965. Pucci rugs, first presented in 1970 at the National Museum of Decorative Arts in Buenos Aires, have been reissued in historic prints like Occhi, which is shown in the book on the bedroom floors of illustrious design couple Delphine and Reed Krakoff’s children. Although the rugs are woven vertically, like a tapestry, Pucci didn’t want them hung on walls, saying, “It’s a bit like having a girl you’ve asked to lunch sit at a different table from you. How can you get to know her?”

“It was his love of storytelling that inspired him to produce works where the figurative and the abstract would meet — reimagining a world colored in his favorite hues and signed off with his name,” writes Laudomia Pucci, Emilio’s daughter, pictured in a Gaetano Pesce Up armchair upholstered in a Pucci print. Photo by Lapo Quagli

Emilio Pucci stands in front of a model of the lunar excursion module at the NASA Space Center, in Houston, on September 30, 1969. Photo courtesy of NASA

Lissoni, by his own account a minimalist designer, recalls being initially overawed by the endless array of Pucci colors and patterns when he began collaborating with the brand. He wound up creating a system of modular cubes, with the fabric serving as a common denominator among the elements. Other modern collaborations established by Laudomia include the Madame chair designed by Philippe Starck for Kartell, the Cities of the World coffee cups by Matteo Thun for the Illy Art Collection and Patrick Norguet‘s Rive Droite swivel armchair for Cappellini, to name just a few. “My problem is not to honor history but to give it wings and project it into the future,” says Laudomia, expressing something one can imagine her father saying. In 2014, almost 60 years after he designed his Battistero scarf, in 1957, she had the design scaled up to literally wrap the Florence Baptistry (battistero) for an art installation titled Monumental Pucci.

Drawing for Duomo panel, 1974. Photo courtesy Emilio Pucci Archive, Florence

Items from the company archives and contemporary Pucci objects can be seen at the Heritage Hub — as the Palazzo Pucci, redesigned to include displays and shops linking the company’s past, present and future, is now known, as well as in Unexpected Pucci. This visual compendium reveals a universe of design for which Pucci is not so well known today. We see that, in spite of his traditional roots (or because of them), the Prince of Prints was forward thinking and outward looking. Pucci put his signature flourish on patterns that were flexible — first for fashion, then for furnishings and objects. Whether on fabric or foam, shelves or sails, as he first explained some 70 years ago, the ornamental designs work in “continuous motion.” Venturing into nontraditional design partnerships, he laid the groundwork for a future brand, a classic legacy Laudomia Pucci continues today. It is, perhaps, only to be expected.