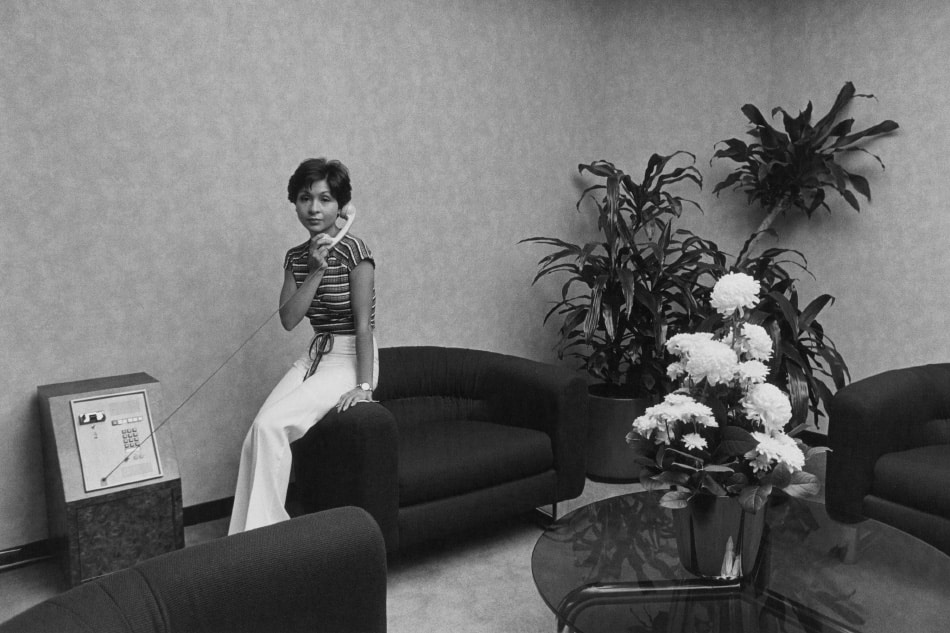

April 22, 2018Photographer Susan Ressler embarked between 1977 and 1980 on a project documenting office interiors and employees, as in Jet Propelled, above. Top: The Capital Group (from the Los Angeles Documentary Project, 1979–80) features a pair of T.H. Robsjohn-Gibbings for Widdicomb benches. All photos © Susan Ressler from the book Executive Order: Images of 1970’s Corporate America (Daylight Books)

The American office has long served as an incubator for modern and contemporary domestic design. In the economic boom following World War II, such manufacturers as Herman Miller, Knoll and Steelcase built their reputations on efficient modular work stations for the clerical class and sleek, high-end furnishings that exuded prestige for power lobbies and executive suites — designs that would often find their way into newly built suburban homes. By the end of the 1970s, the forms and materials of both contemporary commercial and residential design had morphed into a more space-age sensibility, with rounded edges, glistening glass, mirror-polished metal, shiny marble and burnished leather. It is that era — between the mid-century modern depicted in Mad Men and the greed-is-good ostentation of the 1987 film Wall Street — that acclaimed documentary photographer Susan Ressler captured and has now, four decades later, published in the evocative Executive Order: Images of 1970’s Corporate America (Daylight Books).

“I chose the spaces I photographed from 1977 to 1980 for the futuristic flair of that look,” the Taos, New Mexico–based Ressler says, “focusing on form and making it cool and impossibly clean.” She characterizes the resulting images of banks and corporate headquarters in Southern California, Denver and Albuquerque as a critique of corporate culture. “One can never see power, only its effects,” she says, explaining her experience photographing these environments. “It gave me a strange feeling of awe with a simultaneous chilling effect. I imagined that once I had gone, a vacuum cleaner would suck up every footprint, and a butler would dust off any residue of human presence.”

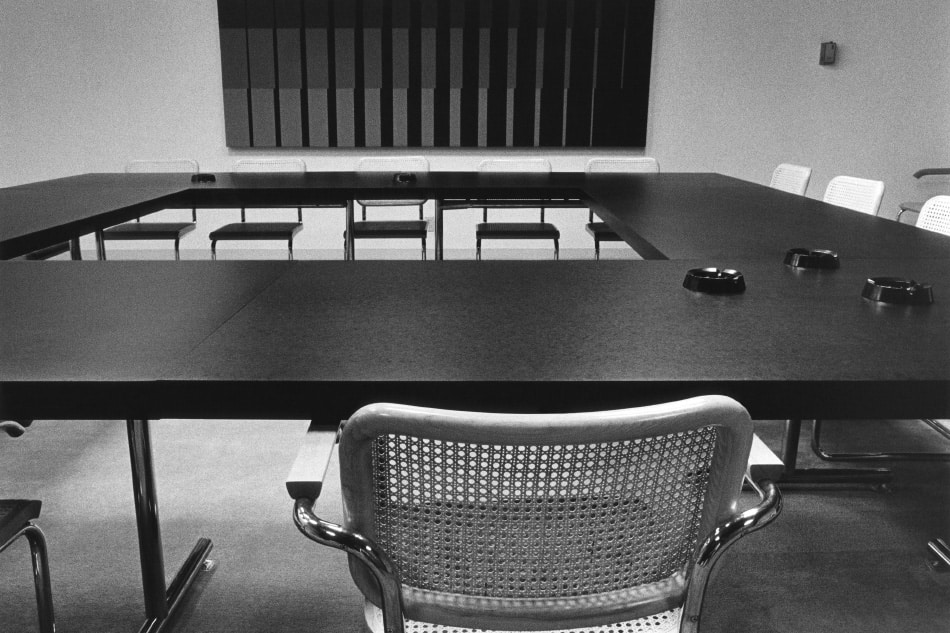

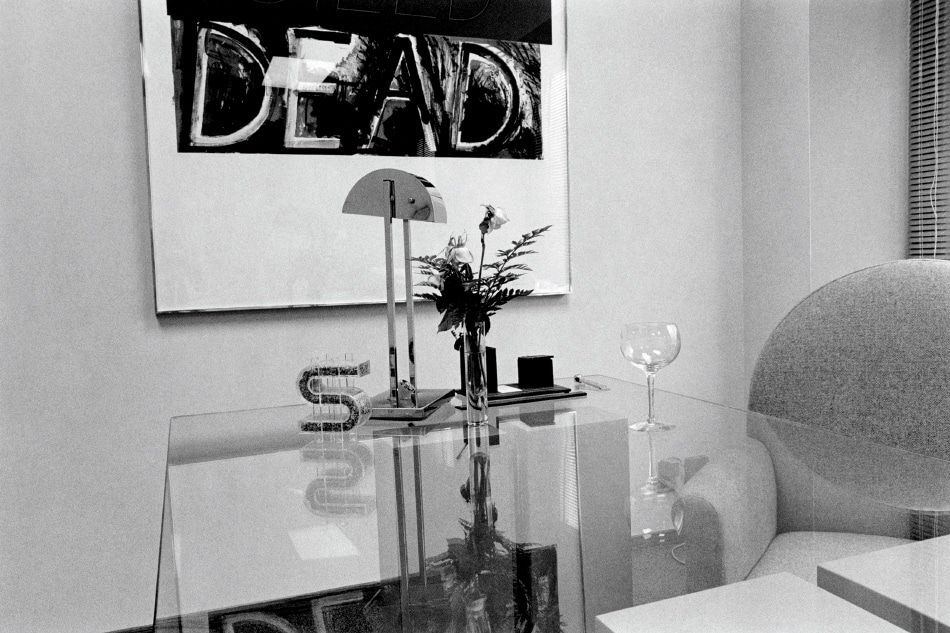

Design aficionados will delight in the details of the book’s time-capsule interiors: supergraphic wall murals, geometric and abstract art, Edward Fields–style rugs, macho trophies (mounted aircraft, diving helmets, globes) and, most notably, classic and still-desirable furniture by the likes of T.H. Robsjohn-Gibbings, Charles and Ray Eames, Marcel Breuer and Hans Wegner, along with the iconic de Sede Non Stop sofa.

Atlantic Richfield Company (ARCO) is Ressler’s “most geometrically complex photograph,” Mark Rice says in the book’s epilogue. Of the space, which includes an Alexander Calder mobile, Ressler says, “The artifice of this interior, no matter how tasteful, is ultimately hollow.”

Ressler once wrote that she used “formal geometry to construct arenas of financial power as sterile, isolating spaces . . . emblematic of consumer capitalism.” Above, Tapes features Hans Wegner Round chairs with cane seats.

These totems of success, writes Mark Rice, professor and chair of American studies at St. John Fisher College, in the epilogue to Executive Order, “shows us what some of the power elites in the 1970s once thought with great confidence or arrogance their future would be.”

Few might have imagined that interiors from the disco and polyester era would still resonate today. “These images feel very current, and many of the pieces and trends have come back into vogue,” notes Los Angeles–based interior designer Oliver M. Furth. “In the world of Instagram and Pinterest focusing on a single picture, a book like this brings the context into focus as well.”

Furth points to 1970s designers like Joe D’Urso, Ward Bennett and Bray-Schaible as again relevant today. “Wall-to-wall carpeting, polished chrome, smoked glass, rounded corners on furniture and large expanses of marble or plain wood paneling are also being looked at with fresh eyes,” he adds. “And the de Sede sofa couldn’t be more in fashion than it is now.”

“Chrome and glass have stood the test of time,” says Atlanta interior designer Stan Topol. “And contemporary furnishings opened the doors to the finest art the world had seen since the Impressionist movement.” Indeed, the interiors captured in Executive Order made abstract art by Alexander Calder, Gene Davis, Bruce Nauman and the like a focal point.

The art project that begat Executive Order began with a simple errand. “I walked into a bank and walked out with photographs of it,” says the Philadelphia-born Ressler, who cites Dorothea Lange as an early influence. Ressler began her career documenting an impoverished First Nations reserve in northern Quebec, Canada. “I had a crisis of conscience about exhibiting such private images,” she recalls, “so it was imperative for me to turn my lens not on poverty but on the ‘upper crust.’ ”

Her photographs of business interiors led to an invitation to participate in the Los Angeles Documentary Project (1979-80), a National Endowment for the Arts photographic survey of the city. Her goal, she says, was to “document the familiar world of finance in a new way. I recently read a somewhat amusing classification system: ‘Office buildings can range in style from caviar to Spam.’ I would have to say that I chose caviar.”

Ressler is pleasantly surprised that, 40 years on, the images in Executive Order not only read as a socioeconomic history but also constitute a period-design sourcebook. “I knew I had gained entry to very rarefied venues, and that few would have access to them,” she says. “I hope the viewer is seduced but pulls back in the end, wondering where they stand.”

Or Support Your Local Bookstore