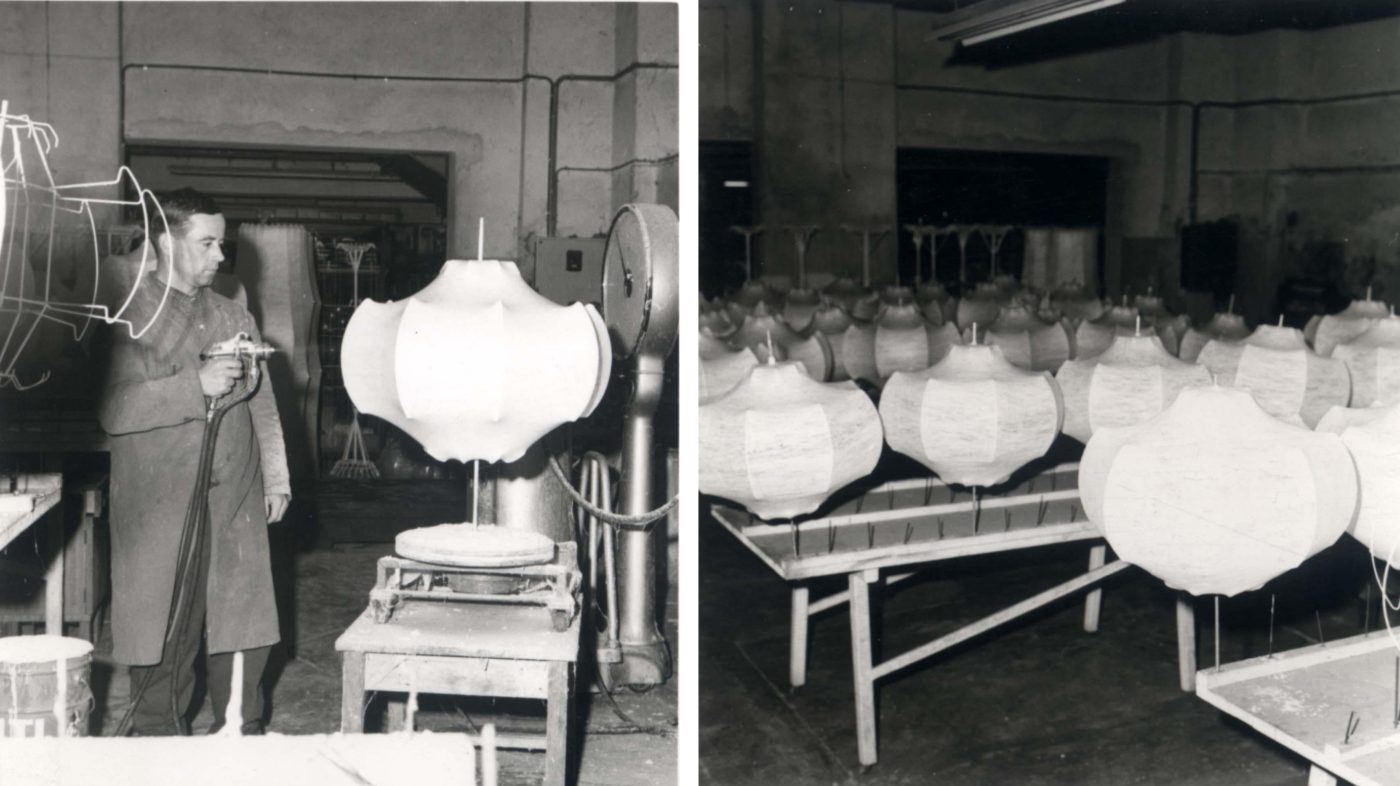

February 16, 2020More than sixty years ago, an Italian inventor/entrepreneur named Arturo Eisenkeil imported a new spray-on polymer from the United States to a factory in Merano, Italy. It had originally been used to protect packages for the U.S. military during World War II. A few Italian designers, including the great Achille Castiglioni, were invited to make light fixtures from the polymer. Castiglioni, one of a generation of designers who helped revive the Italian economy during the postwar period, and an inveterate tinkerer, was intrigued by the novel material — which, when shot from a spray gun at a spinning object, encased it in a kind of shroud.

Castiglioni and his brother Pier Giacomo created a series of metal frames that, wrapped in the polymer, became floor lamps (Gatto) or pendant lights (Viscontea and Taraxacum), all released in 1960. Around the same time, the designer Tobia Scarpa (son of the famed Italian architect Carlo Scarpa) created a floor lamp called Fantasma (1961) using the technique.

The Cocoon series, as it came to be known, served as the basis of a new company, FLOS, which was founded in 1962 by Cesare Cassina and Dino Gavina in Merano. Sergio Gandini joined the company’s board and became the firm’s CEO shortly thereafter, moving the headquarters to Brescia, where he and his wife, Piera, owned an influential furniture store. By the mid-1960s, FLOS — meaning “flower” in Latin — was one of the companies making Italy a “dominant product design force in the world,” in the words of Emilio Ambasz, the architect and design curator at New York’s Museum of Modern Art from 1969 to 1976.

The Castiglionis’ contributions to FLOS — and to lighting — go beyond the Cocoon series. Among the firm’s most famous products is the Arco floor lamp, whose long steel arm curves overhead from a Carrara marble base to a chrome ball shade. (In its obituary for Achille Castiglioni, the New York Times described the light as “a sly solution to hanging a lamp in a room without making a hole in the ceiling.”) The Arco has been in continuous production since 1962.

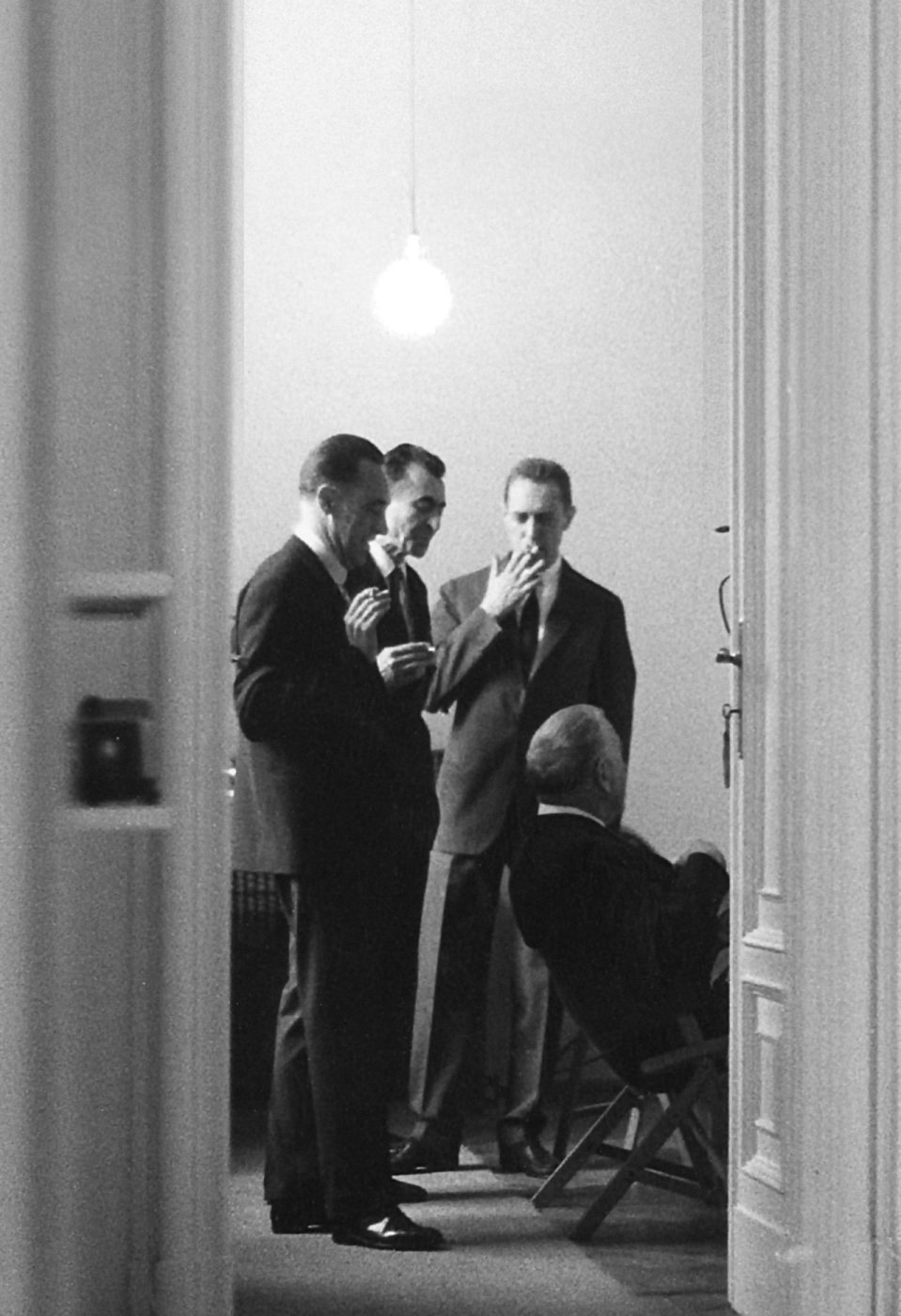

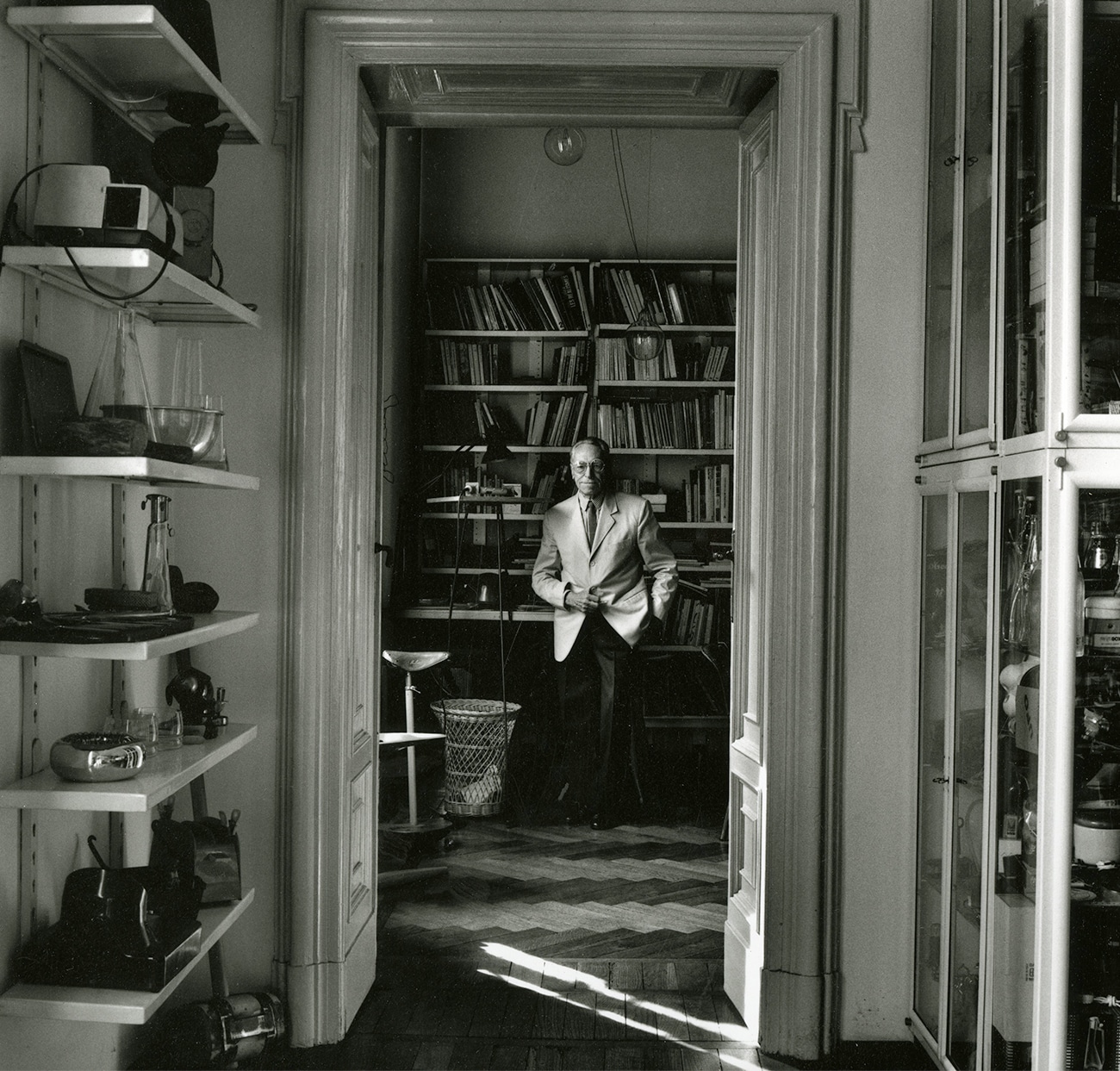

Achille Castiglioni also helped Gandini determine FLOS’s products, communication strategy and image (as did Scarpa). “FLOS was like a family to him,” says his daughter Giovanna Castiglioni. His involvement helped the firm attract attention globally. Paola Antonelli, the senior curator of the architecture and design department of New York’s Museum of Modern Art, who was taught by Castiglioni at the Politecnico di Milano in the 1980s, has described him as “like a comedian from the silent movie era, nervous, chain-smoking, always in motion, playful, and quite mischievous.”

The same description nearly fits Philippe Starck, another designer who has made hugely successful products for FLOS, starting with his first piece, the Ará lamp, from the late 1980s, which is no longer in production. His association with the company continued with a deliberate cliché. “What everybody subconsciously thinks a lamp is” is how Starck described his plastic table lamp, molded to resemble a ceramic base and fabric shade.

Designed for Manhattan’s Paramount Hotel in 1991, the Miss Sissi lamp was extraordinarily popular — FLOS sold 100,000 in the first year — bringing Starck, and the company, freedom to experiment. (In 2012, a concept was developed for a version of Miss Sissi made of polyhydroxyalkanoate, a water-biodegradable biopolymer manufactured from the waste of sugar beet and cane production.) Starck continues to design for the company; his most daring products include floor and table lamps with guns as bases (2005). His latest FLOS creation is La Plus Belle, a full-length oval mirror with LEDs incorporated into its frame, which is set to make its North American debut in April.

These days, top designers are free agents. Like Starck, Jasper Morrison, Piero Lissoni, Antonio Citterio, Marc Newson, Konstantin Grcic, Marcel Wanders and Sebastian Wrong have all collaborated with FLOS. Wanders helped extend the Cocoon series with Zeppelin (2005), in which, it seems, an entire chandelier had been wrapped in the polymer, and Chrysalis (2011), a standing lamp that may be the most restrained item in the line.

The newest member of the Cocoon family is by London-based Michael Anastassiades, whose other clients include Herman Miller, Cassina and Bang & Olufsen.

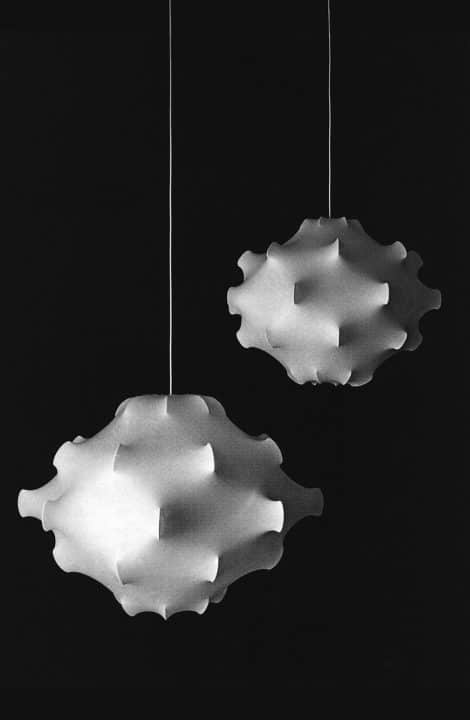

When FLOS invited him to work with the spray-on polymer, he was a bit concerned that there were already too many Cocoon lamps. “It was so saturated it was almost like it had been exhausted,” he says, noting that he remained intrigued by the material. “It produces this beautiful quality of light,” he continues, while the glowing space it encases “is like a metaphor for the bulb inside.” He decided to try to do something new with the technique.

Anastassiades noticed that previous Cocoon lamps were all radially symmetrical — variants on cylinders or spheres that would look essentially the same from any angle. He went for asymmetry: “I wanted to break the mold of having repeated segments spun around.”

One of his many experiments involved a pair of metal rings interlocking at 90 degrees, one extending down below the other. Without access to a polymer sprayer in his London studio, Anastassiades did the next best thing, covering the rings with spandex. He was encouraged by the result.

But there’s nothing like the real thing. In Brescia, Anastassiades watched the first Overlap lights being made. “As the frame is spun around,” he says, “the fiber attaches itself to the frame, but every now and then the person making the piece stops the spinning and attaches the fibers that are loose.” For that reason, no two fixtures are precisely the same, he notes: “Every piece is unique.”

“It’s a new direction — different from the existing fixtures,” Anastassiades says, summing up his Cocoon adventure. “But it’s very much in line with my usual pared-down aesthetic.”

FLOS, meanwhile, continues building on the work of its original designers, rereleasing pieces by the Castiglionis in new colors and finishes (including the brothers’ Toio floor lamp in matte black, a 1stdibs exclusive) and incorporating lighting technology not available half a century or more ago. The Castiglionis’ Bulbo57 was updated last year with an LED element that mimics the original tungsten filament. Giovanna Castiglioni is grateful. “This allows us to keep Achilles’s heritage and philosophy alive for a new generation of consumers,” she says.

Her father is also alive to a new generation of designers. “Achille did not leave just a single heir to design, but many of them,” Giovanna says.