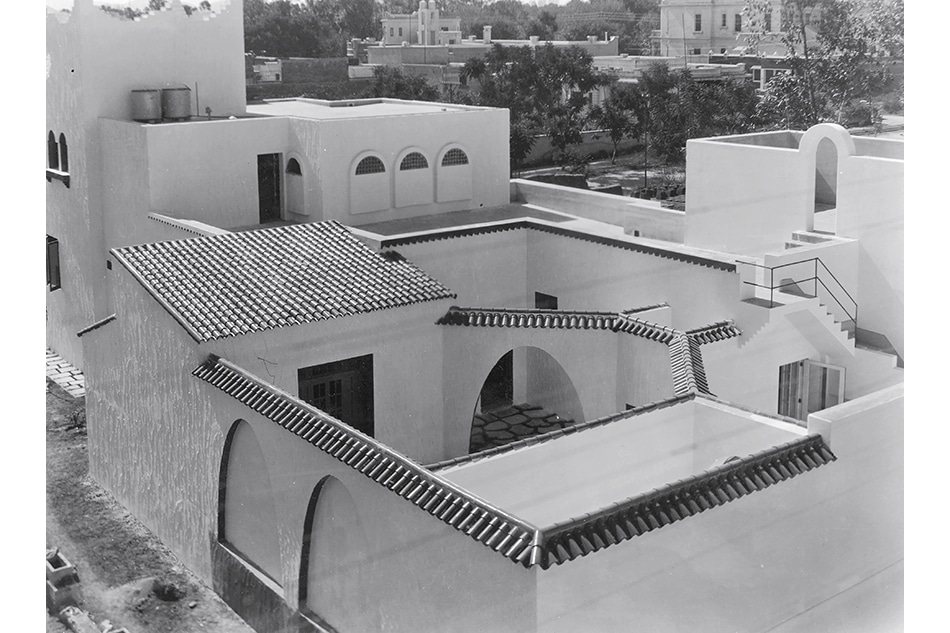

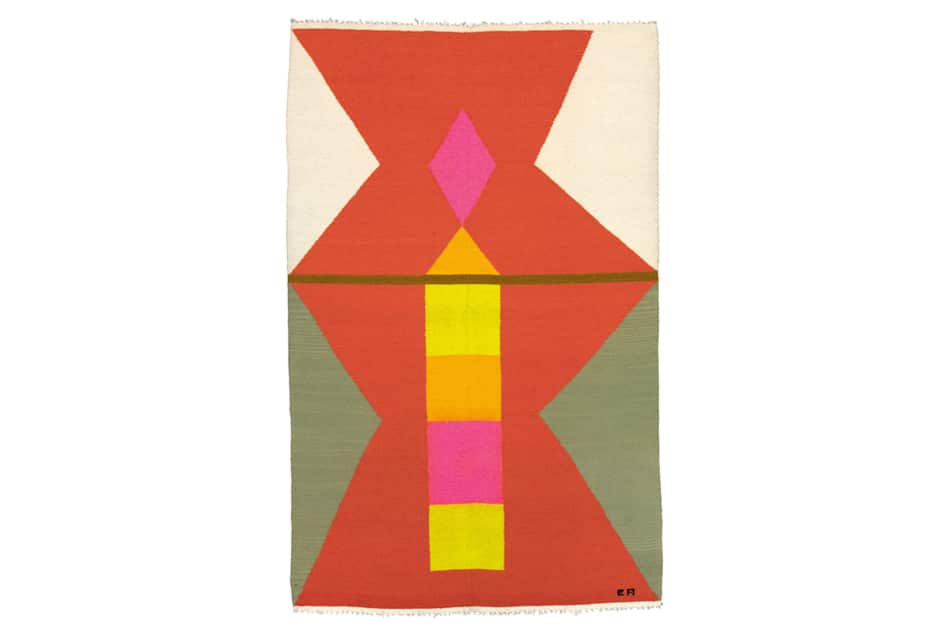

September 18, 2017Part of the second edition of “Pacific Standard Time” — a Southern California–wide collection of exhibitions — the Los Angeles County Museum of Art’s new “Found in Translation” celebrates the interplay between 20th-century designs created in Mexico and California, including Dora De Larios’s mid-1960s Warrior (photo by Robert Wedemeyer © Dora De Larios). Top: A mid-1960s Mexico City residence by Francisco Artigas, Francisco Luna and Roberto Luna. Photo © Roberto and Fernando Luna

The best museum exhibitions take something seemingly obvious, a subject we think we know, and surprise us by deepening and enriching it. Take the Museum of Modern Art’s Frank Lloyd Wright exhibition this year, which fleshed out our view of the iconic architect.

Opportunities for that kind of edification are thick on the ground this fall with “Pacific Standard Time: LA/LA,” the Southern California mega-show featuring some 70 exhibitions at institutions ranging from the Getty Center to the Hammer Museum at UCLA and the Museums of Contemporary Art Los Angeles, all looking at the region’s pervasive Latin influences. (Pacific Standard Time’s first edition, focusing on the development of the area’s modern and contemporary art scene, took place in 2011.)

Architecture and design fans have a bounty to explore, in particular “Found in Translation: Design in California and Mexico, 1915–1985,” which just opened at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) and will be on view through April 1.

“It seems so obvious that there would be connections, with two places sharing borders, sharing climate, sharing population, but what’s surprising is how deeply the influence is felt,” says Wendy Kaplan, one of the show’s curators and head of the museum’s decorative arts and design department.

It’s big topic, as Kaplan and her cocurator, Staci Steinberger, found out. “Initially, we thought we’d do a more modest show, just about Mexican influence in California, because that was at least marginally within my comfort zone,” recalls Kaplan.

But Joan Weinstein, of the Getty Foundation, the primary funder of the PST initiative, suggested that it would be a lot more interesting if the show would go in both directions. Kaplan — a design historian who doesn’t specialize in architecture and notes the strong presence of that field in the show — had to stretch.

“I gulped and said, ‘Truly, I don’t know anything really about how California influenced Mexico.’ It just wasn’t in our purview,” she relates. “And Joan said, ‘Well, why don’t you check it out?’ ” Kaplan and Steinberger did just that, heading off to Mexico City to start their research.

A 1933 watercolor of the Wallace Neff– and Carl Oscar Borg–designed Arthur K. Bourne House, in Palm Springs, illustrates the ways in which Southern Californian architects adopted and adapted the look of Mexico’s tile-roofed adobe buildings. Photo courtesy of The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens, San Marino, California, archNeff

“Found in Translation” grew to encompass more than 250 works, from Carleton E. Watkins’s haunting and spare circa 1877 photograph Mission Santa Barbara to Pedro Friedeberg and José González’s mahogany Hand chair, from the mid-1960s, evocative of the groovy Pop era.

Fashion, jewelry and pottery are also in the mix, grouped into four categories: Spanish Colonial Inspiration, Pre-Hispanic Revivals, Folk Art and Craft Traditions, and Modernism.

As the curators discovered and have made clear here, the ideas that traveled between Mexico and California didn’t make one-way trips — they bounced back and forth, refracted and took on new forms. Kaplan points to the architectural hybrid Colonial Californiano, essentially what Mexicans took from Californians’ version of their original style.

“It went back to them in a very specific way — Hollywood glamour meets upper-middle-class Mexican aspirational,” she says. By the time composite mission-style architecture reached David Klein’s 1966 poster for TWA, in which Los Angeles is represented by an arched bell tower under an Aztec-like pattern, it was hard to tell who contributed what. The aesthetic evolved and grew richer in transit.

Modernism flourished in both places. The architect Richard Neutra, renowned for his ultra-modern Los Angeles residences, had deep ties to Mexico. After lecturing there in the 1930s, he became well published in the country, and one of the designers from his studio, German-born Max Cetto, would go on to have a very successful career in Mexico, working with some of the country’s top architects.

“Mexico embraced Neutra’s notion of what we’re calling a vernacular modernism — one that really pays attention to integration with the landscape, the local conditions, as opposed to the cliché of the International style, where you have a vocabulary that’s supposed to be suitable anywhere,” says Kaplan.

David Klein‘s 1966 TWA poster advertising the airline’s Los Angeles service reveals the extent to which Aztec and mission-style motifs had become intrinsic to Southern California’s aesthetic. Photo © Museum Associates/LACMA

Luis Barragán, easily Mexico’s most famous modern architect, was a Neutra fan. “One of our little icons in the show is Barragán’s own copy of Neutra’s book Survival through Design, translated into Spanish and annotated all over in Barragán’s handwriting,” says Kaplan. (It was borrowed from the Barragán Foundation.) Also on view is a beautiful conte crayon drawing that Neutra did of Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo when he traveled with them to visit pre-Hispanic sites.

The influence of émigré artisans is another subtheme of “Found in Translation.” The American silver designer William Spratling established a workshop in Taxco, Mexico, turning out designs that riffed on the region’s rich craft traditions. Antonio Piñeda, born and raised in that area, apprenticed with Spratling (as well as with craftspeople in Mexico City) and eventually got his own line at Gump’s department store in the United States; his 1952 jade and silver necklace is in “Found in Translation.”

Although the Olympics are often thought of only in the context of sports, the show sees many design connections between the games’ 1968 edition in Mexico City and its 1984 outing in Los Angeles. “You have these two cities that are very similar in terms of low-rise sprawl,” says Kaplan. “It was urgent to have a graphic identity to get people around and, especially, one that could communicate with people who spoke many different languages.”

The show includes a dress-and-cape ensemble designed by British-born, Mexico-based Julia Johnson-Marshall for the 1968 Olympics’ hosts, who helped direct visitors through the city. Incorporating the games’ logo, designed by Lance Wyman, the outfit’s eye-popping, almost hypnotic black-and-white lines presage the bold wayfinding and other graphics created by Deborah Sussman and Debra Valencia for the 1984 L.A. games.

Kaplan enjoyed pushing into unfamiliar territory with the show. “I think if you are going to grow as a scholar, or even as a human being, you have to do things once in a while that scare you,” she says.

The results of her efforts are anything but scary. Indeed, they’ll keep design audiences enthralled this fall.