July 15, 2018The late Robert Indiana found his distinctive artistic voice in brilliantly colorful, text-based Pop works (portrait by Dennis and Diana Griggs). Top: Installation view of “Robert Indiana: Hard Edge,” 2008 (photo © Morgan Art Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York and courtesy of Paul Kasmin Gallery)

One of the most significant careers in Pop art came to a close when Robert Indiana died, this past May, at age 89.

Although his last decades were personally and professionally rough and he fell off the art world’s radar for a time, Indiana’s work of the 1960s and ’70s remains an influential touchstone for both art lovers and the public, some of whom encountered his pieces daily on city streets. We see the world differently because of him.

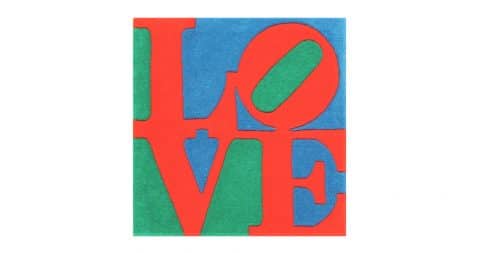

Using text and color in ways that influenced generations of artists, Indiana found a resonant nexus between emotion and graphic punch — a sweet spot that came with its own subtle, and sometimes intriguingly bitter, side note. His “LOVE” series became perhaps the most famous art of the late 20th century, the American Gothic of its time, and its popularity across mediums, from sculpture to posters to postage stamps, demonstrated that it had a life of its own.

“He was an incredible artist, who created his own language,” says Paul Kasmin, Indiana’s last primary dealer, although he hadn’t seen the artist in years at the time of his death. (Indiana’s late works are the subject of a messy legal dispute.)

Love figures prominently on 6th Avenue in Manhattan. Photo by Amanda Hall/robertharding

In 2013, the Whitney Museum of American Art mounted the retrospective “Robert Indiana: Beyond Love,” a persuasive effort that enriched our view of his entire career. I went to see Indiana that year. Getting to him was a journey: For decades, he lived in a decrepit Victorian mansion on Vinalhaven, a remote Maine island accessible only by ferry. There, surrounded by thousands of old copies of the New York Times and quite a few cats, Indiana bitterly nursed various grudges — most prominently about his payment from the U.S. government for creating the LOVE postage stamp, which he said was just $1,000. The scene had a last-reel-of-Citizen Kane quality.

He told me I exhibited “gross negligence” in being underprepared for the interview because I hadn’t seen a nearby billboard he’d designed — true, perhaps, but an odd conversational gambit. He also had fleeting moments of self-awareness. “I’m rather given to melodrama,” he told me. And then he made another revealing statement: “I’m a word person.”

By that, he meant not only his use of text in art but also his ability — and need — to write his own narrative. He was born Robert Clark in New Castle, Indiana, in 1928, later taking the name of his home state as his own. He created a mythology about his family that came to fuel his art, claiming connections to John Dillinger and saying that some of his relatives had shot one another. It wasn’t clear whether these things were true, but in the context of his artistic narrative, it didn’t much matter.

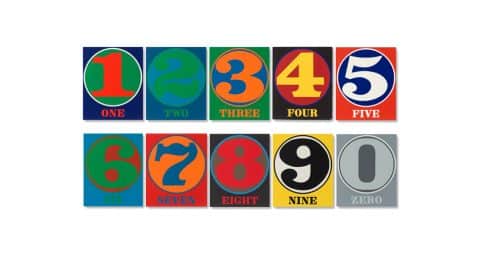

Indiana moved to New York in the 1950s and settled in Lower Manhattan, in the artist hotbed Coenties Slip, becoming one of a handful of young talents who would change the face of art, among them Agnes Martin, James Rosenquist, Cy Twombly, Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns. Ellsworth Kelly, another future titan in the group, was Indiana’s lover, and his hard-edged style became a huge influence on the Midwesterner, as Indiana confirmed to me (noting sadly that he didn’t think the influence had gone both ways). But it was a much older work, Charles Demuth’s 1928 masterpiece I Saw the Figure 5 in Gold, in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, that really set his course, right down to the fonts of the letters and numbers. “It’s my favorite painting,” he told me.

Robert Indiana surrounded by work in his Spring Street, New York, studio, 1966. Photo by Basil Langton

Early on in the movement, it was Indiana who was the great Pop art hope. “If you had asked around then [who the leading figure was], it wouldn’t have been Warhol,” says Barbara Haskell, the curator who organized the Whitney’s retrospective. “Indiana was the guy who was called in a review ‘the pacesetter of the 1960s.’ ” (It’s interesting to imagine a world where Indiana, not Warhol, became the Pop icon.)

When the artist first introduced his “LOVE” series, in 1966, it happened to “coincide perfectly with the counterculture, and it came with a huge marketing blitz,” says Haskell. The bright stacked letters were everywhere. But that very ubiquity led critics to turn on him as early as 1972. Did his success make people resentful? Indiana seemed to think so. And, as Kasmin notes, “he was his own worst enemy” in some of the ways he handled the negativity.

What the critics and the public missed, Haskell explains, was the depth of Indiana’s work over time: “He brought a lot of layering.” Because of the “LOVE” series, she says, many people assumed the artist was some kind of sunny optimist, but in truth, the tilting O was visual evidence that he saw cracks in the facade of everything.

Both Haskell and Indiana himself have argued that his “American Dream” painting series was his most artistically significant body of work. The American Dream, 1, from 1961, now in the collection of New York’s Museum of Modern Art, features four target-like shapes arrayed with numbers and letters, including the phrase “TAKE ALL”; subsequent works proclaimed “EAT” and “DIE.” As Indiana reminded me, “Eat was my mother’s last word before she died.” In other words, there was always a complicated undercurrent in his clean-lined Pop works.

“He tapped into something about the dark side of the American story,” Haskell says. “He did it in the high-keyed color of advertising, the cheerful language. That was brilliant. It had an emotional resonance.”

For collectors, a market condition that was perilous to Indiana’s reputation in his lifetime is now something of a boon: There’s a lot of work out there. On 1stdibs, the offerings range from relatively inexpensive prints and posters to unique pieces, including the sculpture LOVE Red Outside Blue Inside, 1966–95, priced at $425,000. Right now there’s a great place to see more of an under-appreciated side of his work:

“Robert Indiana: A Sculpture Retrospective,” on view at the Albright Knox in Buffalo through September 23.

Whether painting or sculpture, Indiana proves again and again what his dealer Paul Kasmin believes about him: “He had a vision and an absolute clarity that made him a truly great artist.”