October 24, 2021Some of Lucas Bscher’s earliest memories involve running around art fairs with his sister, Isabelle, selling catalogues for the booths of their family’s modern-art-focused Galerie Gmurzynska. “We were happy to contribute to the business even back then,” says Bscher, today a partner in the gallery, which has spaces in New York City and in the Swiss cities of Zug and Zurich. (Isabelle is also a gallery partner and the director of North American operations.)

When their mother, Krystyna Gmurzynska — whose own mother, Antonia, founded the gallery in Cologne in 1965 — began letting her teenage son borrow from her art and furniture collection to decorate his bedroom, he hung a Sonia Delaunay painting on his wall. It was only many years later, says Bscher, now 32, that “I understood how special that was.”

Although born into an art-world family, Bscher didn’t begin his own collection until after graduating with a master’s degree in art business from Sotheby’s. When he got his first job, at Simon Lee Gallery, in New York, “I could finally afford to collect,” he says.

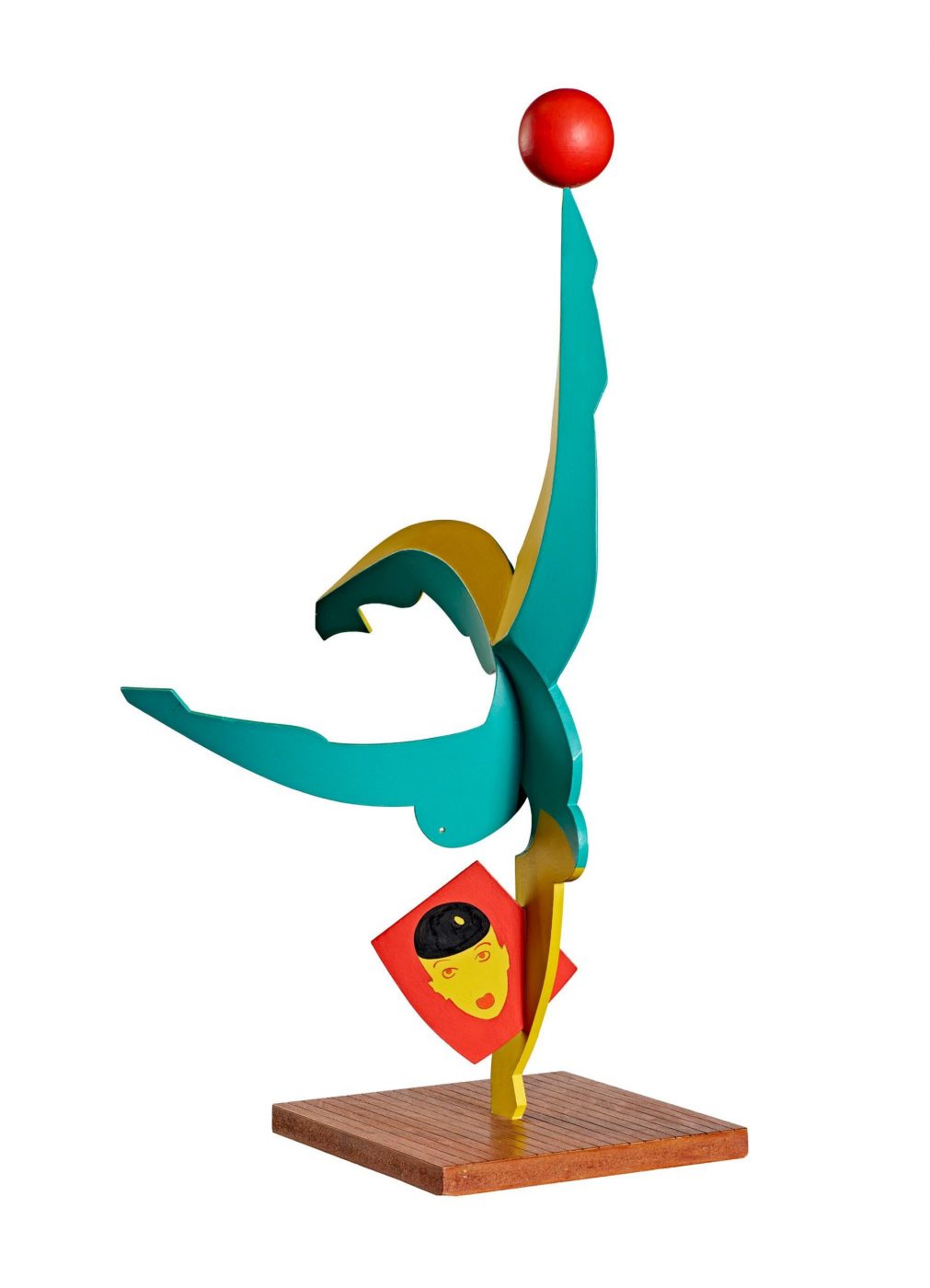

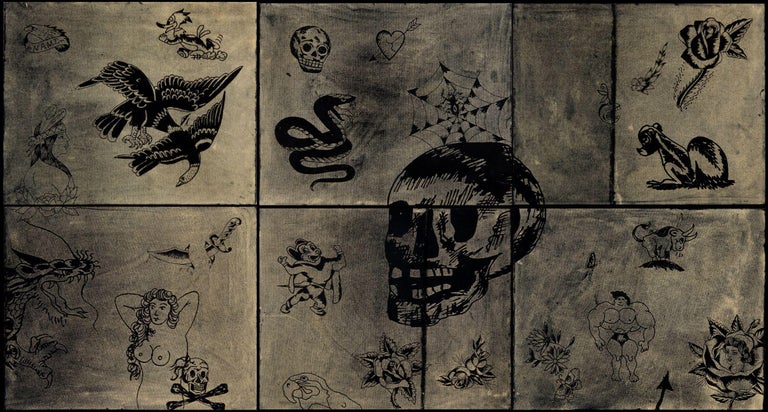

His still relatively limited budget at the time prompted him to steer away from the mainstream, searching instead for undiscovered, relatively inexpensive treasures. His very first acquisition was a collage by the late assemblage artist Dan Basen, who had an impressive career in the 1960s in New York but has been overlooked since his death, at age 31, in 1970. Another largely unsung name represented in his holdings is Pop artist Ronnie Cutrone, who was Andy Warhol’s assistant at the Factory. Bscher describes his collecting focus as “artists with realistic price points as well as substantial exhibition histories.”

When he officially joined Gmurzynska, six years ago, his inaugural sale was of a work by the bluest of blue-chip modern artists: a porcelain sculpture from Pablo Picasso’s “Tête de femme couronnée de fleurs” series, which a local collector bought at an art fair in Hong Kong.

At the gallery, Bscher brings his own particular eye for the cutting edge to his family’s longtime mission of championing modernist movements, especially the Russian avant-garde, and representing such iconoclastic contemporary artist-designers as Christo and starchitect Zaha Hadid.

He has helped direct Gmurzynska toward some talents who were relatively undiscovered. These include the late South American artists Wifredo Lam and Roberto Matta, whose markets have skyrocketed in recent years. “Their works have not been as appreciated as they deserve to be,” he notes, “but their legacies are finally reaching elevated positions.”

The gallery launched its New York location, on the Upper East Side, in late 2018 with a Lam survey. Since then, Bscher has been splitting his time among the Manhattan and Swiss outposts.

“The core principles on which the gallery was founded are reflected across all of our locations,” he says, noting that first and foremost among these principles is operating as an art gallery not an art dealer. This is a lesson he learned from his mother. “We always have a museum approach to exhibitions, from their curatorial organization to their publications,” he explains.

The American and Swiss spaces do, however, have different characteristics that dictate the specifics of the shows each puts on.

Take the recent Zaha Hadid exhibition, “Abstracting the Landscape,” at Gmurzynska’s Paradeplatz location in Zurich. Hadid herself designed the space in 2016, as one of her final commissions before her death that year, taking her inspiration from German Constructivist Kurt Schwitters. It’s hard to imagine a more fitting place for a show celebrating the fascination with the Russian avant-garde shared by Gmurzynska and the late architect.

Introspective spoke with Bscher recently about the gallery’s program and philosophy, as well as its contemporary collecting strategies and surprising successes.

Can you discuss the gallery’s interdisciplinary approach to art and design? For example, your recent Zaha Hadid show presented the seminal architect as an artist and furniture designer. And you have a Donald Judd chair on 1stDibs.

The history of the Russian avant-garde is a cross between art, design and architecture. Many artists planned cities and made furniture — Delaunay did fabrics. Art and design are inherently intertwined. Hadid’s sketches, in my opinion, are geometric abstractions. She would always deny that she was an artist and insisted that those were architectural renderings, but they were art pieces.

As a dealer who represents artists known for both their paintings and their sculptures, what would you advise collectors who are torn between works by the same artist in two different mediums?

They should follow their personal tastes based on what medium they’d like to live with, but I’d also recommend that they look at which medium has helped the artist make a bigger impact. If they’re only getting one piece by the artist, they should stick with that creator’s signature medium. On the other hand, it’s quite interesting when artists try out a new direction. In most cases, you can still see their traditional iconography in another medium.

Who is a recent discovery in your roster? Is there an artist whose career is making a comeback?

Rediscovery is something we thrive on, because it’s exciting. Since we took over the Matta and Lam estates, there has been an immense resurgence in interest in both artists, with multiple auction records and still much room for growth. Lam’s language is unique both for its representation of the twentieth-century aesthetic and for the personal iconography of his Afro-Cuban Chinese heritage. Matta was decades ahead of his time with his Cubist science-fiction references. His training in architecture allowed him to see space differently — so much so that Marcel Duchamp said no one conveyed space the way Matta did. He was a huge fan and called Matta the most gifted painter.

Have you ever been surprised by the success of an exhibition you’ve mounted?

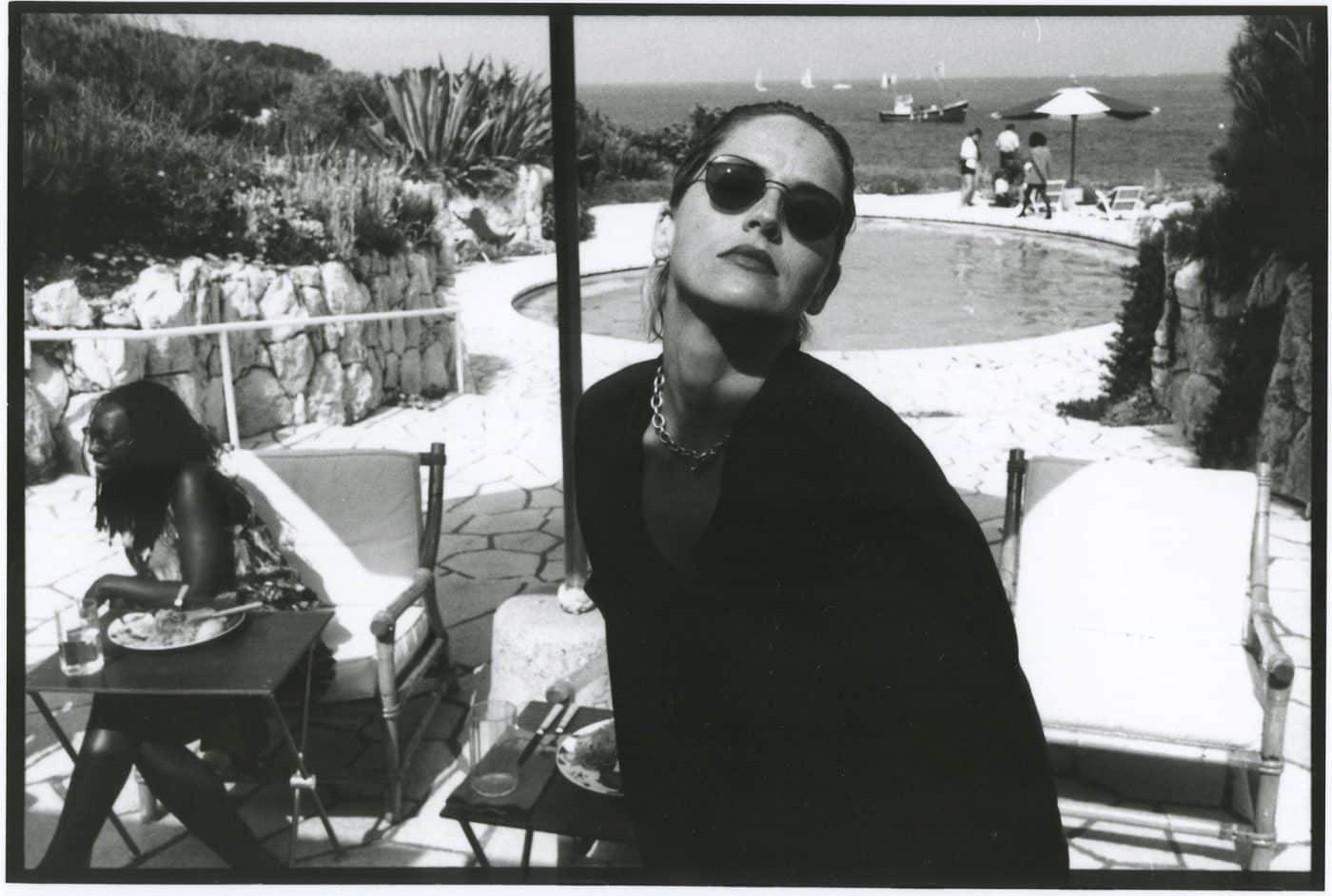

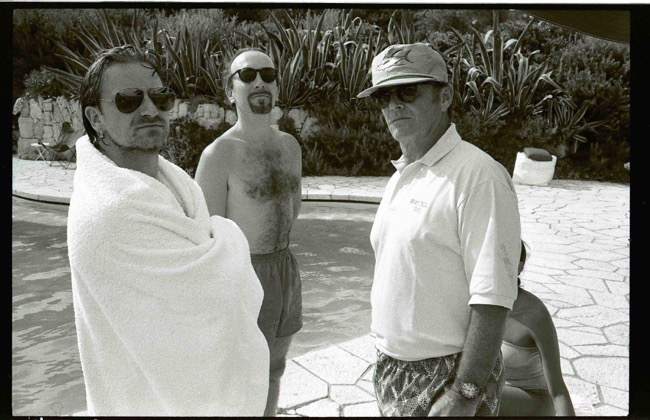

Our observation is that shows of living artists always receive higher demand, while modern art is less fast paced. When we opened our Jean Pigozzi show, “Pool Party in the Snow,” in Saint Moritz in 2017, calls kept flooding in. Our current Zurich show, with the French-Vietnamese-Spanish painter Anh Duong, has been receiving tremendous attention as well.

Is there a piece of art you’ve sold that was particularly hard to part with — that you wish you’d kept?

Almost all of them! I love the early twentieth century, so it’s particularly hard to let go of pieces from that era. But this is our job. Once we had a Picasso painting from his Rose Period. Those works are so rare in the market that I knew we would most likely never sell one of them again.

Is there a cost to following your taste rather than market trends?

My biggest tip is buy what you like. At the gallery, we’ve observed that the collectors who buy out of passion and enthusiasm are also those who end up making smart financial decisions in the long run. Their intuition pays off.