Consummate collector Hubert Zandberg — born in South Africa and based in London — brings a maximalist sensibility to the art- and objet-filled homes he designs for clients, many of whom are as acquisitive as he is (portrait by Boyd Alexander). Top: Using finds from Paris’s Clignancourt flea market and Istanbul’s Grand Bazaar, plus custom pieces, Zandberg created a flamboyant French take on old Hollywood glamour for a petite pied-à-terre in the City of Light’s 8th arrondissement. Photo by Nicolas Mathéus

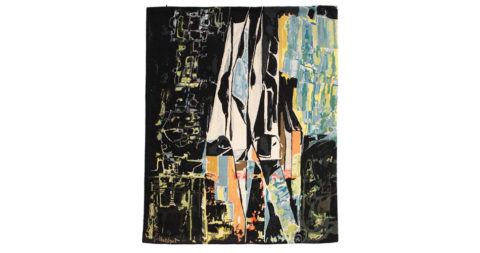

One way to make a tiny apartment seem expansive is to keep the number of pieces in it to a minimum. That’s not an approach Hubert Zandberg ever considered for his own 300-square-foot Paris pied-à-terre. Zandberg, who is based in London, picked nearly 50 artworks, ranging from a painting of a young Dustin Hoffman by Dawn Mellor to an abstract by South African artist Nicholas Hlobo, and hung them “salon style” (read: covering every surface). But his placement of the works eased disparate objects into compelling compositions. In Zandberg’s view, “A mass choir can sing as harmoniously as a duo or trio — it just takes a better conductor.”

Moving the 50 artworks and hundreds more objects to Paris barely made a dent in Zandberg’s collections. They fill his homes, including a former canal keeper’s house in London, a cottage in his native South Africa and an apartment in Berlin, bought specifically to hold his trove of mid-century Brazilian furniture. Plus, he has a storage space full of everything from contemporary art to ships-in-bottles to African textiles to contemporary ceramics to dice (yes, dice, a collection begun in Las Vegas).

And he continues collecting at flea markets at a furious pace. (Zandberg also buys online once he has established direct contact with a dealer and has made his requirements clear.) A constant shopper, and former retailer himself, he believes in keeping the wheels of commerce turning. When a dealer won’t give him a good price, Zandberg responds by saying, “You’re not playing the game properly. You need to set a price that turns the wheel.”

Zandberg custom designed not only the rosewood bedside table but also the linens in the bedroom of this London home, a three-story structure located near the canals of Little Venice. In lieu of artwork, he framed a series of antique needlepoint fabric squares and placed the collaged swatches above the nightstand. Photo by Simon Upton

“I would love to only design and collect for myself,” says Zandberg, whose office is around the corner from London’s Portobello Road, which bills itself as “the world’s largest antiques market.” “But for better or worse, I have to have clients.” Luckily, he adds, “I choose my clients carefully.”

The ones he chooses indulge — even encourage — his compulsion to collect. For the owners of a house on the Black Sea, he acquired more than 100 1970s-era blue-glass vases — some aqua, some turquoise, some midnight blue — and organized them on custom-built shelves. Individually, each may be kitsch, but together they’re a kind of art installation. The idea that, when seen in multiples, the ordinary can become compelling is Zandberg’s excuse to acquire in quantity. When he walks through stores or flea markets, the junk becomes a haze, he says, and the objects worth having “present themselves clearly.”

Zandberg explains that he doesn’t buy objects for their intrinsic value but for the “conversations” they will have with pieces he already owns. “The fun, for me, lies in creating dialogues,” he says. “The best moment is when I place the object. Sometimes, I buy a piece and I’m not ready to place it — I get to keep the excitement for another day.”

Zandberg traces his collecting compulsion to his childhood in the Karoo, the semi-arid region of south-central South Africa. “There’s a very particular light and a very particular kind of nothingness,” he says of the environment. “The emptiness may explain my desire to surround myself with lots of things. Who knows?”

During his Karoo upbringing, Zandberg recalls, there wasn’t much to do except run around picking up natural objects, like stones and feathers and skulls. He filled his first cabinet of curiosities at the age of four and by seven had given his whole room over to his collections. And he hasn’t stopped.

The idea that, when seen in multiples, the ordinary can become compelling is Zandberg’s excuse to acquire in quantity.

In the little Venice kitchen, Sol & Luna leather chairs surround a classic marble-topped Tulip table by Eero Saarinen. The sofa is a vintage Danish piece. Photo by Simon Upton

At South Africa’s Stellenbosch University, Zandberg studied law and administration, hoping to become a diplomat, but political changes in South Africa made that career impractical. Instead, he took a job at a lifestyle concept store near the university while continuing his studies. In 1996, he moved to London, where he helped renowned designer David Champion run a posh shop and eventually partnered with him on interiors projects. “That taught me design is a pragmatic field — you have to think on your feet,” he says.

In 2002, Zandberg founded his own firm. All his clients are collectors, many of museum-quality pieces. Zandberg says the trick is taking those precious objects and working them into environments that don’t feel museum-like, to “show them in a contemporary, casual way while reflecting their gravitas.” In the case of a client with a world-class trove of Islamic and pre-Islamic art, Zandberg injected contemporary paintings and sculptures, modernist furniture and African artifacts into the mix, to create a home where the important antiquities “are presented with dignity, but without being overbearing.”

Another client hired Zandberg to turn an apartment in Paris into a crash pad for visiting friends and family. Since no one would live there, the client told him to “go as wild as you possibly can.” So Zandberg created an homage to Tony Duquette, the Los Angeles designer who spent much of the 20th century seeing how many colors and patterns he could use in one room. “The apartment is pure theater, almost tongue-in-cheek,” he explains. “We wanted to see how outrageous we could be and still vaguely make it work.”

Much of what he used in that apartment, he says, is kitsch. Kitsch is usually thought of as bad, but Zandberg has a more nuanced view. The bad can be divided into the bad-bad and the good-bad, he notes. Of course it’s the good-bad he searches for.

And how can he tell the difference?

“It’s my job to know,” says Zandberg.

Hubert Zandberg’s Quick Picks on 1stdibs