June 20, 2016The New York Botanical Garden’s latest exhibition, “Impressionism: American Gardens on Canvas,” features flower-inspired art by American Impressionists, including the William de Leftwich Dodge painting shown above, The Artist’s Garden, ca. 1916 (photo courtesy of the Neville-Strass Collection). Top: Accompanying the show is a greenhouse display that brings the artists’ works to life (© Robert Benson Photography).

This year marks the 125th anniversary of the New York Botanical Garden (NYBG), and not surprisingly, the garden is in celebration mode. Its latest crowd-pleasing exhibition, “Impressionism: American Gardens on Canvas” (on display until September 11), takes its inspiration from a small group of late-19th-century American artists working at about the time of the garden’s founding. Their loose brushstrokes, lush palettes and choice of subject matter were so clearly influenced by the work of European artists like Claude Monet and Edgar Degas that they became known as the American Impressionists.

The group included not only such well-known names as Childe Hassam, John Singer Sargent and William Merritt Chase but also less-familiar ones, like Matilda Browne, William De Leftwich Dodge, Maria Oakey Dewing and John Henry Twachtman. They were all painting at a time when interest in gardens and gardening was growing in the United States.

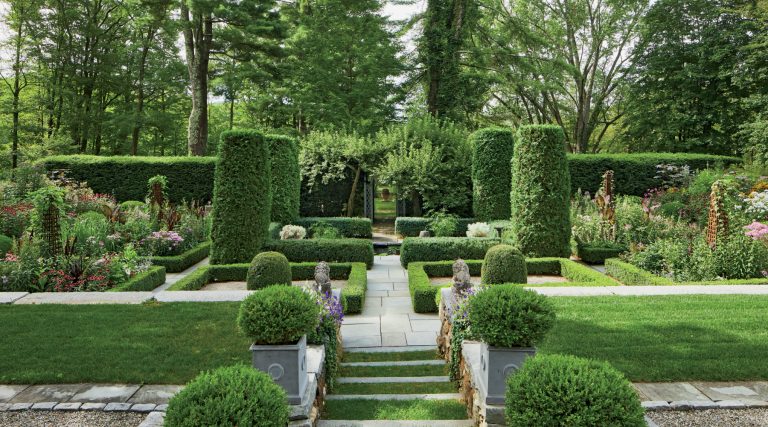

As it did in its previous summer shows (notably last year’s “Frida Kahlo: Art, Garden, Life”), NYBG presents landscapes sprouted both from the ground and on the canvas. Visitors can view a delightful selection of paintings, curated by Linda S. Ferber and shown in the garden’s Rondina and LoFaro Gallery. Standouts include Hassam’s Celia Thaxter’s Garden, Appledore, Isles of Shoals (ca. 1890), with its somewhat unruly flowers and moody sky, and Browne’s weighty post-bloom Peonies (ca. 1907). Then they can head to the Enid A. Haupt Conservatory to see how NYBG’s talented garden curator, Francisca Coelho, has re-created the painted scenes in a live botanical setting.

Coelho has designed and planted two long herbaceous-style beds profusely planted with sunflowers, peonies, poppies, cosmos, clematis, columbine, larkspur, hollyhocks, delphinium, irises, sweet peas, lilies, lupins and phlox. These lead to a re-creation of a rustic New England summer house, with weathered cedar siding and a vine-covered porch. In crafting this imaginary garden, Coehlo studied historical accounts and examined the plant records of poet Celia Thaxter’s garden on Appledore Island, off the coast of Maine, a gathering point for many of the artists represented in the show.

Protected from the vagaries of drafts, winds and pests, this Impressionist garden is all delicious fantasy.

The house-like structure is immersed in blooms that would have been found in poet Celia Thaxter’s garden on Appledore Island, Maine, a gathering place for many of the Impressionists in the show. Photo © Robert Benson Photography

The plants selected by Coelho and her team were carefully propagated to bloom simultaneously rather than sequentially, and when a flower withers or fades, it is whisked away to be discreetly replaced by another glorious specimen. Protected from the vagaries of drafts, winds and pests, this Impressionist garden is all delicious fantasy. The colors and scents of the profusion of flowers make it easy to see why they were such an inspiration to the artists in the show.

In another nod to the garden’s anniversary, a fully revised and much-expanded version of the classic tome The New York Botanical Garden is being released. Edited by NYBG president and CEO Gregory Long and Todd Forrest, the institution’s vice president for horticulture and living collections, it includes new photographs by Larry Lederman (including an amazing aerial shot of the conservatory) and essays by many members of the garden’s staff on different aspects of its work today.

The cascading stream in NYBG’s outdoor rock garden was restored in 2014. © Larry Lederman, courtesy of Abrams

The book recounts how the garden came into being and how it has become one of New York’s foremost cultural institutions. (Last year, it attracted more than a million visitors.) This fascinating history begins with a trip to England in 1888 by native New Yorker Nathaniel Lord Britton, a well-educated botanist, and his young wife, Elizabeth, also a trained botanist. Having visited the Royal Botanic Gardens in Kew, they returned to New York fired up with the idea that their city should have a botanical garden to equal the great ones of Europe.

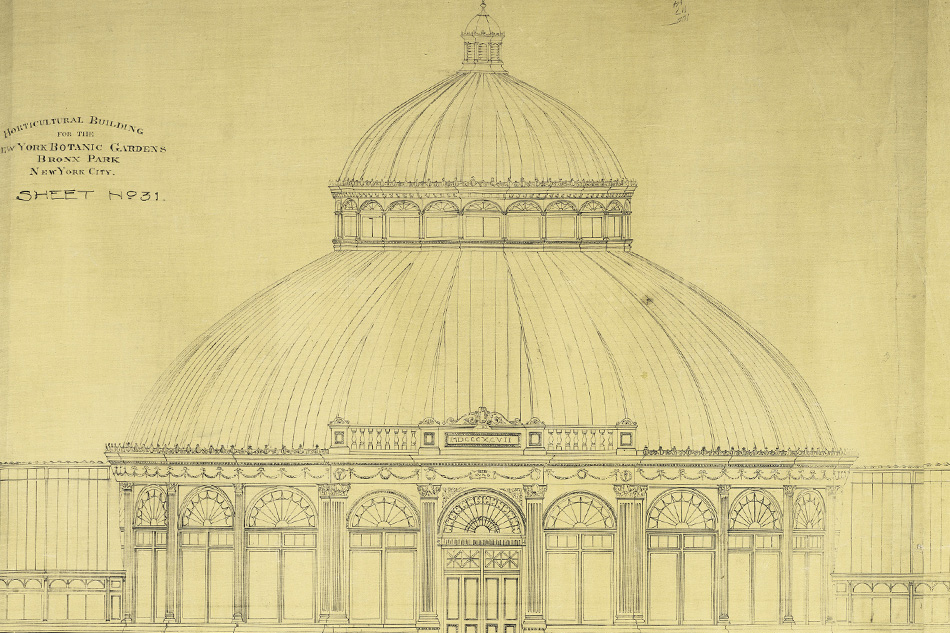

After three years of tireless campaigning by the Brittons, the state of New York set aside 250 acres of forest land in the northernmost part of the Bronx “for the collection and culture of plants, flowers, shrubs and trees” and “the advancement of botanical science and knowledge,” as NYBG’s original charter from the state reads. Planning for the landscaping and architecture got under way under the direction of Calvert Vaux, who’d earlier collaborated with Frederick Law Olmsted on Central Park.

There would be forests, meadows and garden displays, as well as a monumental library (today a priceless repository of rare garden books) and a crystal-palace conservatory inspired by the famous Palm House at Kew. Botanical research would go hand in hand with horticultural displays and public lecture programs. There would also be an herbarium and rotating exhibitions, the latest of which, of course, celebrates those American Impressionists, who were producing vital work at the same time that the Brittons were busy with an important project of their own.