Old stereotypes die hard. Say “family business” and most people still think “father and son.” Yet several leading interior designers have followed their mothers into “the trade.” To us at Introspective, this is an intriguing development, especially since many of the designer offspring are men. We wondered: Is it nature or nurture that made these individuals pursue design as a profession? Has it changed significantly over a generation or two? Do professional children influence their mothers in their approach to design and style as much as their mothers influenced them?

For our informal survey, we interviewed London’s Rita Konig and her mother, the legendary interior designer Nina Campbell; Kendall Wilkinson and her mother, Alice Wiley, who both have their own decorating businesses in San Francisco; Gideon Mendelson and his now-retired mother and former business partner, Mimi, of the New York–based Mendelson Group; and, finally, Tommy Clements and his mom, Kathleen, the sole duo in our story who work together as business partners, in Los Angeles’s Clements Design.

Nina Campbell & Rita Konig

April 11, 2016Rita Konig came to interior decoration through her mother, Nina Campbell, who apprenticed with John Fowler before launching her own eponymous home shop and decor business in London. Photo courtesy of Rita Konig

Nina Campbell was just 19 when she started out in the mid-1960s as an apprentice to the late, great John Fowler at Colefax and Fowler, in London. Back then, “the business was extremely different, much more formal,” she says. “John was working for people who already had the house, who already had the furniture. You weren’t going out and shopping. You were only occasionally knocking down walls. It truly was interior decorating. . . . Today, you’re designing for people who are buying new houses all over the world, who have no furniture at all and need soup-to-nuts service.”

After being schooled by the master, the independent-minded Nina set out on her own and soon made waves by first designing the posh Berkeley Square nightclub Annabel’s for her friend the aristocratic entrepreneur Mark Birley. She and Birley then opened one of the first luxury-lifestyle shops on Pimlico Road, and she alone went on to establish her own eponymous line of fabrics and wallpapers, now produced by Osborne & Little. (It should be noted that such industry was unheard of among posh young women in London at the time.) To squeeze in as much time as she could with her eldest child, Rita, before the latter returned to boarding school after the Christmas holidays, Nina began taking her to Paris for the Maison & Objet fair.

Rita loved it. Today, she still recalls the marvel of shopping with her mother at the gourmet food shop Fauchon and “the magic of visiting D. Porthault, with all the prints, boxes and tissue paper and the ladies ironing in the shop.” These rarefied experiences, Rita believes, all contributed to her love of retail presentation and aided her when, just out of school, she ran her mother’s home decor shop in London’s Chelsea neighborhood.

“I loved selecting new things, updating the colors, making it younger,” Rita says. Yet she admits finding it a bit annoying that her mother got all the credit — a sign, she eventually realized, that, much like her mother, she needed to be her own brand. That is how she first started writing on decorating and design in 2000.

Reflecting on how she and her mother compare as tastemakers, Rita observes that their differences are more generational than stylistic. “Today, there are various degrees of interior design. Not everyone wants to buy into a decorator’s ‘look’ anymore. Maybe it’s the effect of Domino” — the much-loved American shelter magazine where she served as editor at large from 2005 to 2009, before it shuttered. “They want people who can facilitate what they want, who can shop for them.” And, of course, shopping is among the things Rita loves best. In fact, it’s why she launched her own retail line last year.

Nina, who calls her daughter “a terrific talent,” agrees that their styles are similar, although Rita is “slightly freer, especially with color.” To highlight this point, she recounts how a young Rita wanted her mother to paint the door of their new house pink rather than the chic Parisian dark green Nina had selected. Not wanting to offend her daughter’s budding aesthetic sense, Nina told her that as lovely as pink might be, that color paint was too expensive. Later, she learned this excuse had caused her child to worry terribly about the family’s finances. Today, Nina notes her daughter has a house with a bright yellow door.

Mimi and Gideon Mendelson

When New York–based Gideon Mendelson launched his own design studio, after working with Steven Gambrel, he tapped his mother, Mimi, to join him. Although she’d been easing into retiring from her own interiors business, she jumped at the opportunity. Photo courtesy of Mendelson Group

Mimi and Gideon Mendelson partnered up seven years after he graduated from Columbia University with a degree in architecture. He’d minored in film studies at college and after graduating had a brief stint at the talent agency William Morris before working at Steven Gambrel’s design studio. If it took him a few years to home in on interior design as the right profession, the same could be said for his mother. But when she realized her calling, in 1974, she was already a mother and a working stockbroker, which made her a trailblazer back then. Ever the professional, she went back to school to get a degree in interior design before opening her own design studio in tony Scarsdale, New York.

When her son joined the business, he was already well-versed in the basics. So, from the start, they did most things together, including project management and accounting. But he also played the role of apprentice. “I took over the technical drawing — we were still using ink and Mylar,” he says, “and I did all the schlepping!”

Growing up, Gideon remembers evenings spent watching TV with his mother while leafing through Architectural Digest and House Beautiful during commercial breaks. Together they’d comment on the balance of the furnishings, the palettes and the layering of patterns in the rooms.

Were these shared pastimes what turned her son into a designer? Mimi isn’t so sure. “Children show you who they are. When he was a toddler, he would comment on the architecture in the neighborhood. ‘Nice shutters,’ he would say, or ‘Big window!’ ”

Yet her son feels that his early life with his parents — “doing a lot of drawing and talking about color, form and proportion; traveling and visiting museums; and meeting lots of people” — had an important influence on his career choice.It has been his architectural training, however, that has determined the way he approaches projects. “I start my work thinking about function and circulation rather than rugs or fabrics,” he says. That said, his years working with his mother have dramatically altered his process: “When I started, I was very concerned about how everything looked. Now I’m more concerned about how it feels. I’m more focused on telling stories and creating atmospheres for living.” This concern for “mood and drama” also derives, he thinks, from his college film studies.

Mimi, in turn, has been greatly influenced by her son in regard to the evolution of her taste. “His academic experience certainly enlightened me, and his love of mid-century design proved contagious,” she says, adding, “I’m much happier with gray than I used to be.”

Alice Wiley & Kendall Wilkinson

San Francisco’s Kendall Wilkinson, left, followed her mother, Alice Wiley, into the world of interiors, and, today, each continues to learn much from the other. Photo by Peter Hall

Alice Wiley is another mother who credits her child, Kendall Wilkinson, with updating her style. Calling her daughter “an icon,” Alice says, “Watching Kendall’s work evolve has helped me to integrate my ‘old’ tastes for the warmth of color and lovely wood with the new. Just the other day, a manager in a showroom I frequent suggested a piece of furniture for a client, and I responded, ‘It’s not contemporary enough.’ He was astounded. As design is ever changing, so am I.”

In 1965, when Alice launched her design business, she didn’t have what her daughter calls “the luxury” of professional training; she had to depend solely on “her amazing eye for color and scale,” Kendall says. When Kendall later decided to follow in her mother’s footsteps, Alice insisted that she get a design degree. She wanted her daughter to have the confidence of that training and the skills it hones, so that the younger woman would be able to offer a wider suite of services, including interior architecture. It was sage counsel: Today, Kendall’s studio is known not only for being aesthetically adventurous and full service but also for taking on a wide range of residential and commercial projects.

Calling herself “blessed” when discussing her mother, Kendall acknowledges that her own work has “evolved into a more modern aesthetic,” a development she attributes partly to “generational differences and partly to the changing design landscape in San Francisco. When I started out, my clients used to be mainly confined to two affluent zip codes; now they’re throughout the city and Silicon Valley and beyond.”

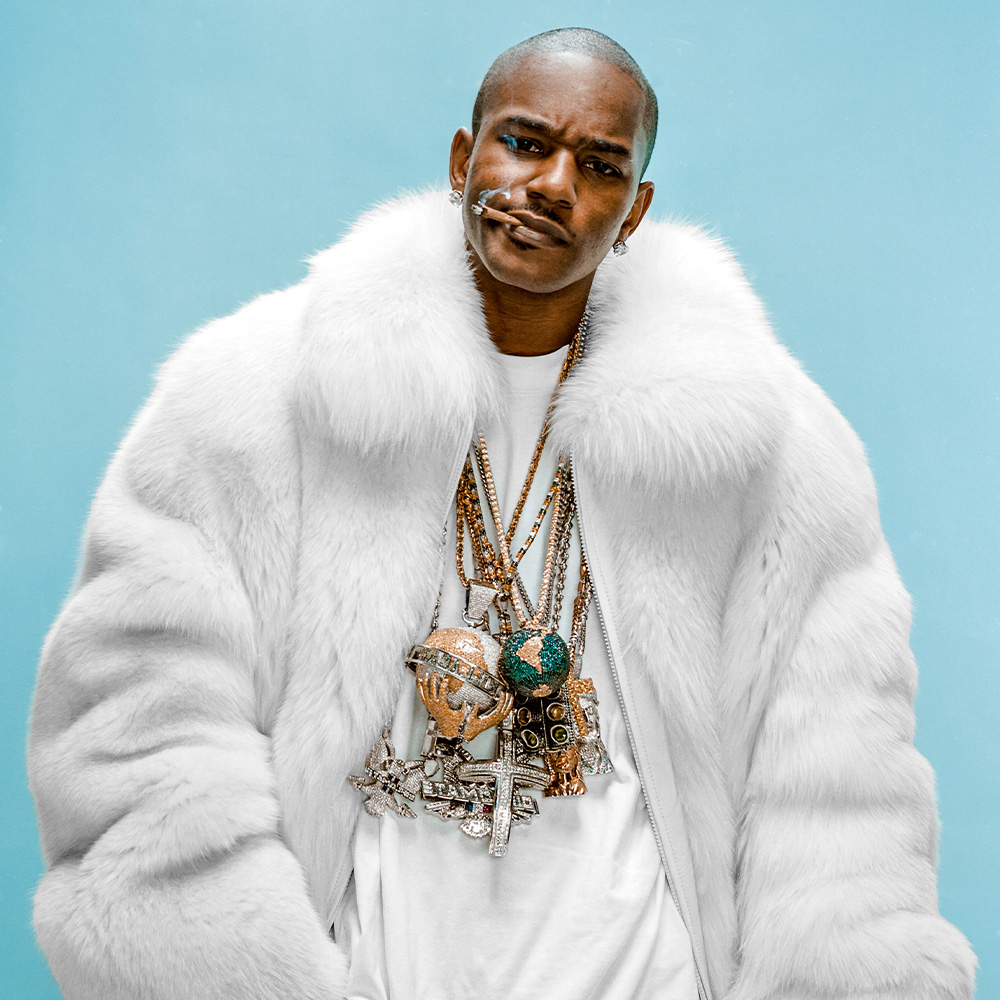

Kathleen & Tommy Clements

Son-and-mother team Tommy and Kathleen Clements run their interior design studio from Los Angeles. Photo by Sam Frost

When Tommy Clements was growing up, he remembers watching his mother renovate or furnish new houses for the family again and again, as they moved every few years. That was because his dad — and namesake — is an NFL coach (currently for the Green Bay Packers). “I was keenly aware that each home had a very distinct feeling when it was complete, and I tried to understand why,” he says. “I think this is when I started to absorb the importance of scale, layout and palette, as well as to appreciate how the architecture of a house informs how its rooms are composed.”

All this decorating prompted his mother to open Sister Agnes, a small antiques shop in New Orleans, in the late 1990s, when her husband was with the Saints and her son was already a teenager. It was only then, Kathleen Clements says, that she “made a full-time commitment to design.”

As close as mother and son are, Tommy says they have very different design approaches, which he attributes to temperament. “I can really get obsessed with the minutiae and all of the small design details, which of course are hugely important,” he says. “My mom is a bit more macro, more visceral. No matter how perfectly planned and thought out every detail is, there still has to be something unexplainable, even magical, to give a home its character and soul. My mom is super-conscious of that feeling, and she forces me to . . . consider the big picture” — a role most mothers could relate too.

As for Kathleen, focusing on the differences between her and her son doesn’t interest her much. “From the moment Tommy and I began working together, we have always collaborated. We have a very similar sense of style, but each of us expresses our style in a unique way. . . . That’s not to say we don’t disagree, but generally the disagreements ramp up the creativity.” What are the they about? Kathleen is too diplomatic a mother to say, which may be exactly why she and her son work together so well.