November 13, 2017MoMA’s “Items: Is Fashion Modern?” focuses on 111 iconic items, including the white T-shirt, “the ultimate sartorial and psychological blank canvas,” according to the show catalogue (image courtesy of Shutterstock/SFIO CRACHO). Top: A detail of an Aran sweater (photos courtesy of MoMA).

The Museum of Modern Art has no clothes, Paola Antonelli discovered upon joining the New York institution in 1994. In the vast design collection, she found every chair imaginable, as well as appliances, tableware, textiles, posters, and, of course, a bug-eyed Bell-47D1 helicopter, but just one garment: a Grecian-style Fortuny gown, donated in 1987.

“I felt that it was missing not your typical kind of fashion but some basics,” recalls Antonelli, now senior curator in the department of architecture and design, as well as director of research and development at the museum. “The equivalent in fashion of the famous Sven Wingquist–designed Self-Aligning Ball Bearing would be the white T-shirt, or the equivalent of the Sacco beanbag chair would be a piece by Rei Kawakubo.” So, she started a list. Titled “Garments That Changed the World,” the handwritten document evolved into the exhibition “Items: Is Fashion Modern?,” which fills the museum’s sixth floor through January 28.

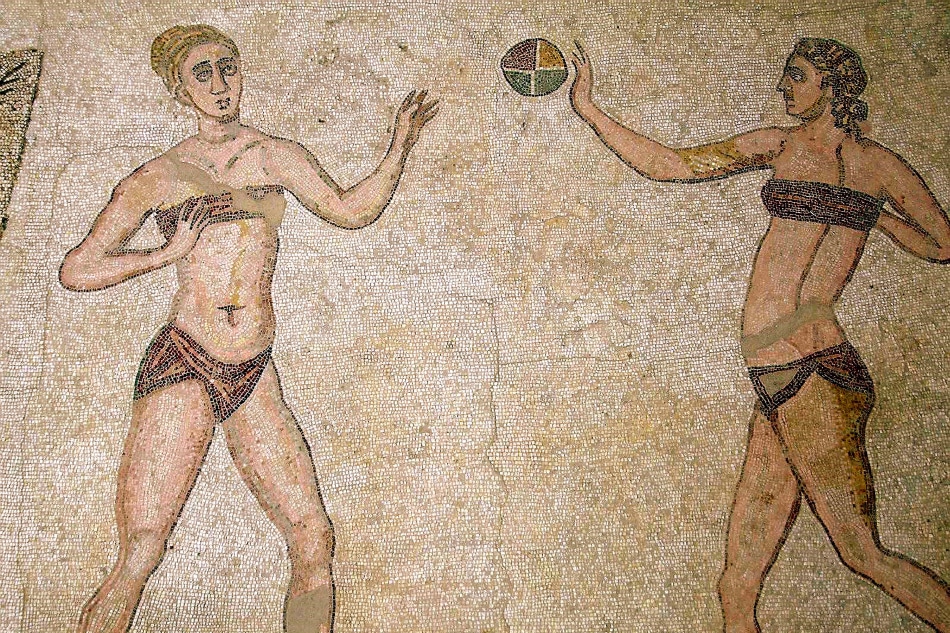

The name nods to MoMA’s only other real foray into fashion: the 1944 exhibition “Are Clothes Modern?” Organized by architect and curator Bernard Rudofsky, that show questioned fashion’s constantly changing styles and body-contorting silhouettes, designed for the masses rather than the individual. It was the work of a bold and whimsical curmudgeon.

Aran sweaters were traditionally knitted using sheep’s wool, whose lanolin made the garments water resistant and thus useful to the fisherman of the isles off the coast of Ireland. Photo © National Museum of Ireland

“With today’s know-how, we are no doubt able to cultivate peanuts on Mars, but nobody knows, or cares to know, how to make shoes for human feet,” Rudofsky once declared. He later took up the task himself, designing Bernardo sandals.

Antonelli credits MoMA director Glenn Lowry with the idea of turning her ambitious list — commenced as “an attempt to see whether our collection might accommodate garments and accessories that would chart the history of modern and contemporary design” — into an exhibition. Narrowing down the document, which had ballooned to more than 500 entries, was a challenge.

Antonelli and her curatorial team arrived at the show’s final set of 111 “typologies” the old-fashioned way: “Lots of arguments! And I’m only slightly joking,” she says. Among the world-altering items represented are Adidas Superstars, the burkini, flip-flops, the Mao jacket, the polo shirt, red lipstick, the safety pin, sunscreen and the Wonderbra. Those that didn’t make the cut include the wedding dress, the hazmat suit and, much to the dismay of Lowry (a connoisseur of foot coverings), socks.

“One of the things that this exhibition does is invite the public to continue the list: So, here are the first 111 to consider, but there are hundreds, if not thousands, more,” said Lowry, wearing Merlot-hued socks, during a conversation with Antonelli staged at the museum to mark the opening. “This is an invitation to think about the way in which fashion is constructed. There is a dimension of trying to understand how something enters into our consciousness as an item of importance.”

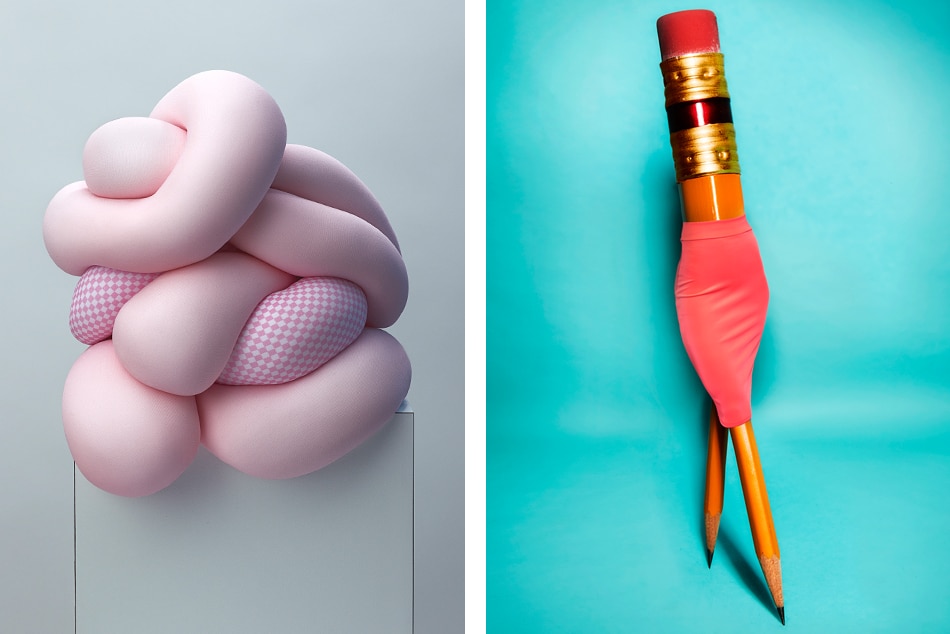

When and in what form it did so was equally important for Antonelli and curatorial assistant Michelle Millar Fisher. Should fleece be represented by a well-worn Patagonia zip-up from the 1980s? Joseph Altuzarra’s equally fuzzy high-fashion version from fall 2014? Both? “The way design is represented at MoMA is ideally in Bauhausian terms — in the representation that made it influential to the world,” explains Antonelli. “To do that for fashion, for each item, we wanted to find the stereotype.” They relied on a simple exercise to make their selections: “Close your eyes, and if you think of that item, what do you see?”

Beloved by rockers, rebels and outsiders, the original biker jacket was introduced by the Schott Brothers, in Manhattan, in 1928. Because of its association with motorcycle club riots, U.S. schools banned the jackets for a time “as an incitement to hooliganism,” according to the catalogue. Photo courtesy of Schott NYC

The biker jacket is embodied by the black cowhide classic Schott Perfecto from the 1950s; the loafer by a 1970s pair of Bass Weejuns; and the shirtdress by a circa 1974 Halston special in buttery Ultrasuede. Icons abound, such as the Birkin bag (represented by Jane Birkin’s Hermès original) and 501 jeans (a much-patched 1947 pair from the Levi’s archive). The turtleneck on display is, of course, black: a 1980 Issey Miyake design accompanied by a video compilation of archival footage (turtleneck-wearing beatniks, artists, Steve Jobs) that provides historical context.

Organized loosely according to such themes as reshaping the body, future and technology, athleticism and power, the items are often represented by multiple variations, bringing the total number of objects to around 350. A procession of platform shoes (Elton John’s among them) chronicles changing materials, while a constellation of lapel pins (an AIDS ribbon, a remembrance poppy) highlights their role in advocacy and self-expression.

The show opens with nearly a century’s worth of little black dresses. Ten standing mannequins clad in creations by designers ranging from Chanel and Dior to Thierry Mugler, Rick Owens and Philippe Starck (who knew Starck devised an LBD for Wolford?) are accompanied by a supine one wearing Pia Interlandi’s 2017 Little Black (Death) Dress, a funeral shroud overdyed with thermochromic ink that can visually register the handprints of mourners. The grave-bound garment is one of the exhibition’s approximately 30 prototypes, “commissioned — and, in a few cases, also loaned — works from emerging and established designers and artists who take the typologies into the future in some profound way,” says Antonelli.

“This is an invitation to think about the way in which fashion is constructed.”

In 1873, Levi Strauss and Jacob Davis patented a process for using copper rivets to strengthen the corners of pants pockets. Their “waist overalls,” like this 1890 pair, were worn by California gold miners and laborers. Image courtesy of MoMA

“Items” is equally in tune with the present and its politics. The hoodie looms large, represented by a wall-mounted cherry-red Champion pullover from the 1980s. In the catalogue that accompanies the show, Fisher charts the garment’s associations with such figures as Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg and Trayvon Martin, shot dead in 2012 by a neighborhood-watch volunteer who suspected the African-American teenager wearing a “dark hoodie” of being “up to no good.” Among four sports jerseys on display is that of San Francisco 49ers quarterback Colin Kaepernick, who famously refused to stand for the national anthem.

Dedicated fans of fashion will find much to admire, including a gleaming Stephen Burrows jumpsuit, space-age creations from Pierre Cardin’s 1964 Cosmos collection and an original Yves Saint Laurent Le Smoking. But the emphasis is on objects — not styles or names — that stand for entire eras and issues. “I hope that visitors recognize the beauty in the everyday,” Antonelli says, “because that is what we have foregrounded rather than the fashion spectacle.”

As for the future of fashion at MoMA, stay tuned. And be patient. “Every seventy years, please come back for a major fashion statement from the Museum of Modern Art,” joked Lowry at the opening, adding, “I hope the next one will happen much more rapidly.”