May 6, 2018Photographer Jade Doskow‘s “Lost Utopias,” on view at Front Room Gallery, in New York, looks at former world’s fair sites in their present-day condition. Works on display include Seattle 1962 World’s Fair, “Century 21 Exposition,” Science Center Arches at Night, 2014 (above), and Montreal 1967 World’s Fair, “Man and His World,” Buckminster Fuller’s Geodesic Dome with Solar Experimental House, 2012 (top).

The past hasn’t been kind to the future.

Or so Jade Doskow learned in 2007 while on a family vacation in Seville. Doskow stumbled upon the abandoned site of the 1992 Seville World Expo, which was focused on the promise of the 21st century. What she discovered was a series of gardens going to seed and buildings locked rather than loaded. This, says Doskow, sparked the idea for a project that would bring architecture, design, culture, preservation, politics and other disciplines into her work as a photographer: She would find the sites of past world expos (also called world’s fairs) and document them in their current state, usually disrepair.

She is now in year 11 of that project, having photographed more than 30 world’s fair sites — ranging in size from 4 to more than 1,000 acres — in North America and Europe. (The project continues, she says, with trips to Asia still to come.) And she has just opened her first New York City gallery show of the photographs. “Lost Utopias,” on view at Front Room Gallery through May 20, features a small selection of the thousands of images she has taken, printed for the exhibition at up to 40 by 50 inches.

Doskow’s photos are not celebrations of what was built but explorations of what has happened to what was built. Indeed, she says she wouldn’t have wanted to photograph happy crowds visiting the fairs; she is more interested in aftermaths and implications. Hers “is a very contemporary view, filled with the modern sense of detachment and irony,” Richard Pare writes in the book Lost Utopias (Black Dog Publishing), which accompanies the exhibition. (Pare’s famous photos of Russian constructivist buildings in their dotage were an important point of reference for Doskow.)

One of Doskow’s shots from the Seville trip is particularly ironic: The environmental pavilion appears about to be overtaken by weeds; entropy, it seems to say, is an environmental hazard. In another Seville photo, a once-bustling entrance courtyard “becomes a secret garden, awaiting rediscovery,” writes urban planner Jennifer Minner in the book’s other essay.

But Doskow, a New Yorker who studied photography at the School of Visual Arts and now teaches there (as well as at the International Center of Photography), found one of her best subjects close to home: Philip Johnson’s New York State Pavilion, left over from the city’s 1964–65 World’s Fair in Queens’s Flushing Meadows–Corona Park, has spent more than half a century deteriorating in full view of drivers on the Grand Central Parkway. Doskow’s photos reposition Johnson’s pavilion and other once-glittering attractions — including the Atomium (Brussels 1958), the Sunsphere (Knoxville 1982) and the Tower of the Americas (San Antonio 1968) — as odd and even menacing structures.

The decrepitude of expo sites is generally the result of lack of planning — getting a fair built is hard enough, and organizers rarely think about what happens after. Cities end up mothballing attractions that were meant to be temporary. In other cases, important structures are neutered: Buckminster Fuller’s gigantic dome in Montreal, a remnant of Expo ’67, stands as a lackluster environmental museum. Many are torn down, although occasionally surrounding fountains and flower beds remain, as if awaiting (rather than recalling) glory days.

And some have been erased entirely. Perhaps the bleakest photo depicts a parking lot, ghostly at night. The caption identifies it as the site of the Japanese Village at the Pan Am Exposition (Buffalo 1901).

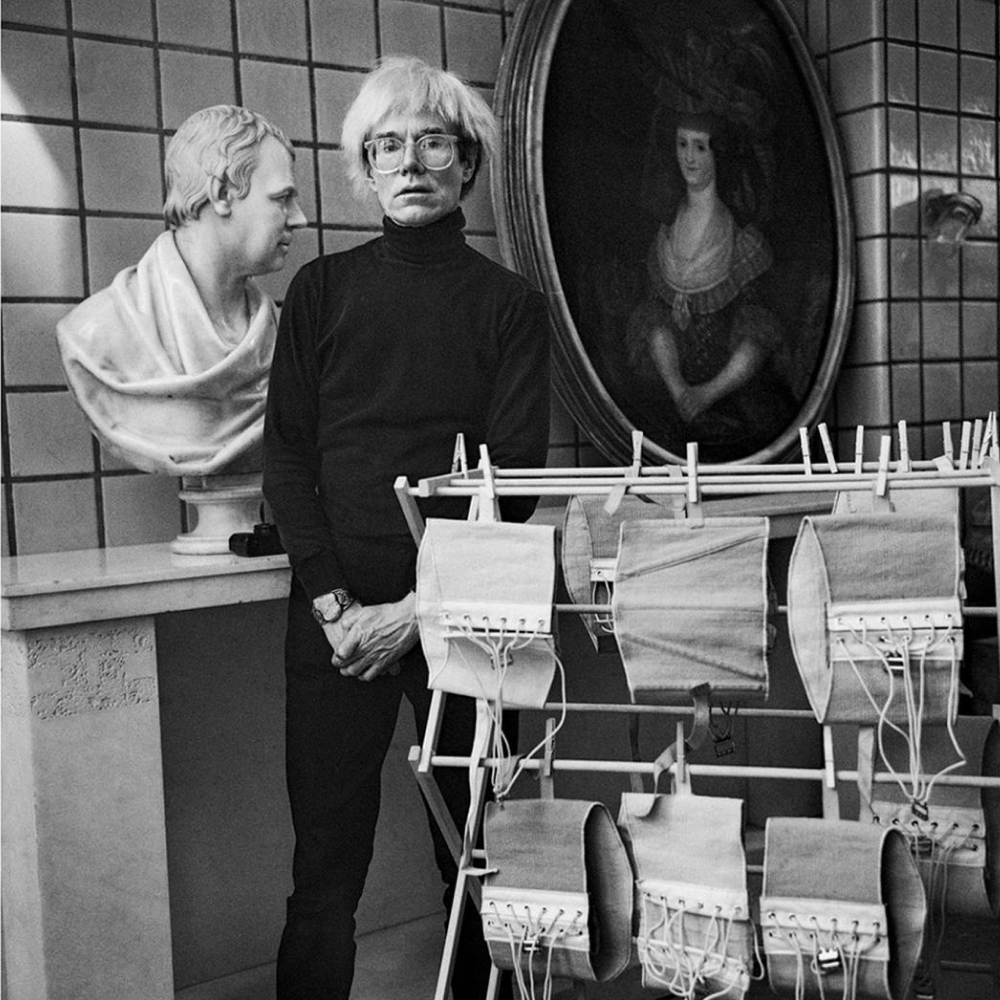

Doskow with her trusty sidekick, an Arca Swiss 4×5 view camera. Photo by Lambert Fernando

There are exceptions. The ersatz Parthenon built for the Nashville fair in 1897 proved so popular it was rebuilt after the expo using more durable materials. And, of course, the Eiffel Tower, erected for an 1889 expo and surrounded by structures from a 1937 expo, is the nonpareil symbol of Paris.

Optimism leading to comeuppance is always a good story line. And it pretty much defines world’s fairs, which have themes like “A Century of Progress” (Chicago 1933), “Peace Through Understanding” (New York 1964–65) and, almost comically, “Celebrating Tomorrow’s Fresh New Environment” (Spokane 1974) but often end in bankruptcy and finger-pointing.

A surprising 25-plus North American cities have hosted world’s fairs, although, tellingly, the last U.S. fair was more than 30 years ago (New Orleans 1984). Doskow has visited all the sites, some many times, with her Arca Swiss technical rail 4×5 view camera (“I carry about fifty pounds of gear on average,” she says).

Her technique accentuates the sense of time passing. As she explains in the book — via a Q&A with critic Vladimir Belogolovsky — she uses “longer-than-normal exposure times to capture smears of movement, such as branches blowing or water flowing, the world in motion around these silent and still structures.”

Doskow says what makes some photographs rise to the level of art is that they are not just “seductive and compelling” but also “multilayered and conceptual.” On those terms, these “Lost Utopias” succeed.

All photos © 2018 Jade Doskow/Front Room Gallery