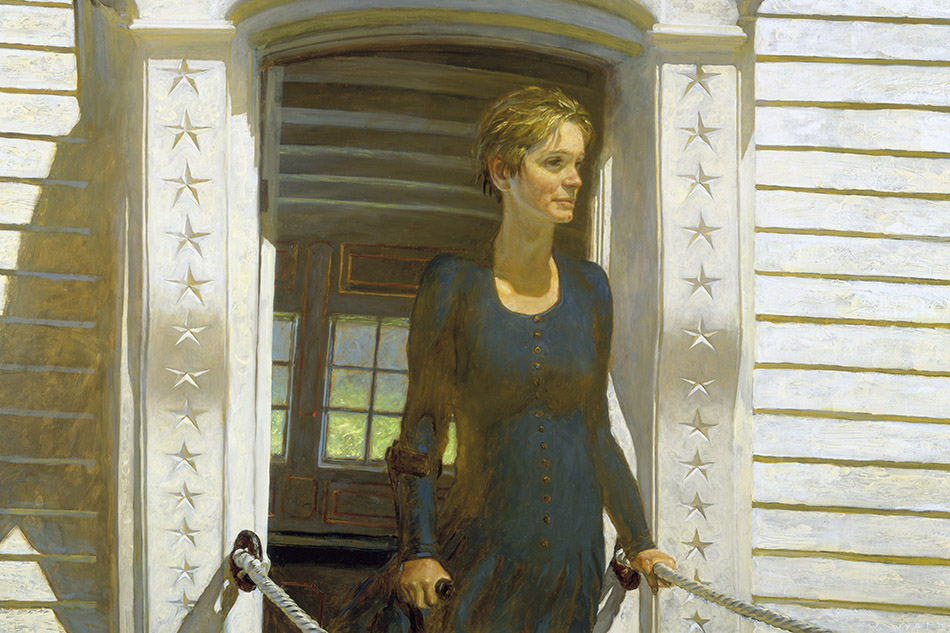

July 16, 2014Jamie Wyeth’s intimate portraits and virtuosic landscapes are the subject of a new retrospective, his first, at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (portrait by Scott Hewitt). Top: The Islander, 1975. All images © Jamie Wyeth, unless otherwise noted, and courtesy of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

When Jamie Wyeth was 11, he convinced his father, the famous realist painter Andrew Wyeth, to let him leave school so he could devote more time to his art. On the family’s farm in Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania — the landscape often depicted in the work of his father and his grandfather, N.C. Wyeth, a prominent painter and illustrator of more than 100 classic novels including Treasure Island — Jamie trained with his aunt Carolyn in the studio of his grandfather, who had died in 1945, the year before Jamie’s birth. At 17, Jamie received his first formal commission: Johns Hopkins asked him to paint Helen Taussig, a pioneering pediatric cardiologist. Capturing the intensity of her gaze and unflinching intellectualism, the vividly realistic portrait unsettled her colleagues, who shunted it to the medical school’s archives in favor of a more sentimentalizing official likeness.

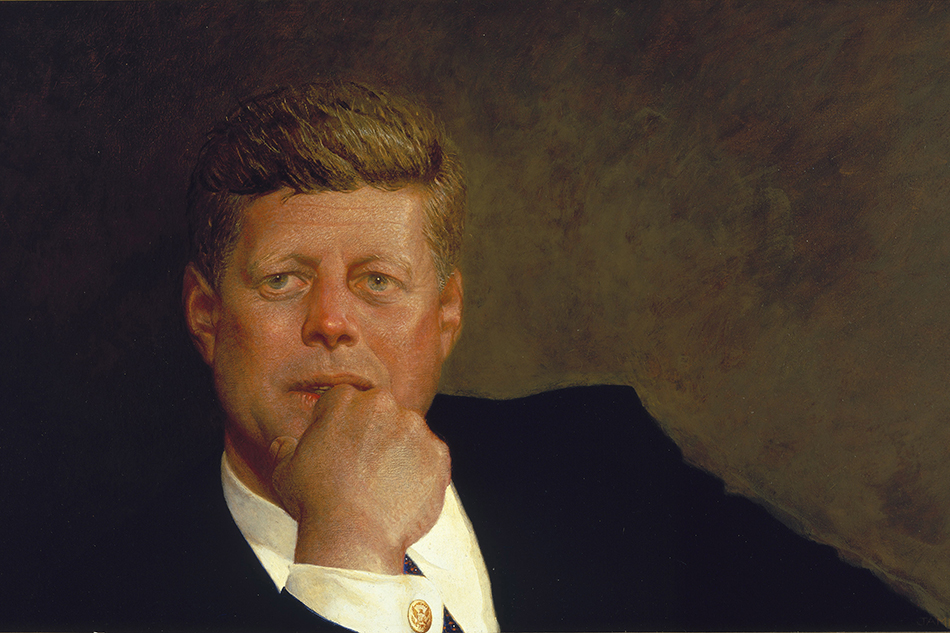

The Taussig portrait will finally be aired in the first comprehensive retrospective of Jamie Wyeth, now 68, on view at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, which opens today and runs through December 28. Flouting the typical presentation of his work within the multi-generational context of his family, the exhibition spotlights Wyeth’s individual achievements. It includes a selection of his precocious childhood drawings (culled from some 1,100 saved by his mother) and focuses on his virtuoso portraits of high-profile figures, from John F. Kennedy to Andy Warhol, as well as his more surrealistic landscapes and seascapes painted in rural Pennsylvania and coastal Maine, two distinct worlds that have been deeply sustaining to him and his family.

The exhibition includes Wyeth’s first commissioned portrait, in 1963, of famous doctor Helen Taussig, which Johns Hopkins asked the young artist to paint when he was only 17.

While anchored in his studios in the Brandywine River Valley near Chadds Ford and on Monhegan Island, in Maine, Wyeth has spent extended periods over the years working in New York. In 1965, he lived in the spare bedroom of his father’s friend Lincoln Kirstein while painting the cultural impresario’s portrait based on copious hours of close observation. A decade later, Wyeth continued his immersive approach to portraiture — which he’s compared to “having a love affair with the person” — during a residency at Warhol’s Factory. The startlingly intimate quality of his portraits extends to his landscapes, which bristle with both beauty and foreboding and are often populated by seemingly sentient animals who eye the viewer. Elliot Bostwick Davis, chair of the art of the Americas department at the MFA, Boston, organized “Jamie Wyeth,” which will travel to the Brandywine River Museum, the San Antonio Museum of Art and Crystal Bridges Museum of Art, in Arkansas. She recently spoke with 1stdibs about Wyeth, an artist many may feel familiar with because of his family’s name even if they do not — yet — know his work.

DO YOU THINK THE WYETH LEGACY HAS BEEN A COMPLICATED ONE FOR JAMIE WYETH?

It’s clearly a double-edged sword. It opened doors early in his career to things, including, when he was 21, painting a posthumous portrait of President John F. Kennedy commissioned by the family. He was a known quantity being a member of the Wyeth family. He describes it himself as allowing him a certain mask — in our exhibition, we show him painting his self-portrait behind a jack-o’-lantern mask in 1972. The show is a chance for Jamie to break out from under the umbrella of generations of Wyeths, to have artists and critics reassess him and to let viewers make up their own minds.

Two landscapes — rural Pennsylvania and coastal Maine, as seen in Berg, 2012 — play a central role in Wyeth’s painting, like in those of his father, Andrew Wyeth, and his grandfather N.C. Wyeth.

IN WHAT WAYS IS JAMIE’S WORK IN LINE WITH HIS FATHER’S AND GRANDFATHER’S, AND WHERE DOES HE STRIKE OUT INTO HIS OWN TERRITORY?

He considered his father, who died in 2009, his closest friend — and he certainly considered him to be a very trusted critic. But aesthetically he is much more like his grandfather. His aunt Carolyn began formally teaching Jamie as an 11-year-old in her studio, which had actually been N.C.’s studio. Jamie talks about having access to all the props that were in the studio — the cutlasses and muskets and costumes — and N.C.’s paintings that were stacked up there. In terms of Jamie’s dynamism of poses and certainly the love of oil paint, that all follows his grandfather.

Two landscapes — Chadds Ford, in Pennsylvania, and parts of Maine — have been a central part of all their work, but how they approach those landscapes is quite different. Carolyn had a surrealist edge, and I think Jamie, probably from her, has the most of it. Jamie does step into the contemporary world far more than Andrew, forcefully pushing himself out of the cocoons of Chadds Ford and Maine into places like the Watergate hearings, where he became something of the court artist, or certainly working with Warhol at the Factory in 1976. That is a big distinction.

Flouting the typical presentation of his work within a multi-generational context, the show highlights Jamie’s individual achievements.

Wyeth painted his Portrait of Andy Warhol in 1976, during his residency at Warhol’s Factory, when the two artists agreed to do a portrait exchange.

ANDREW WYETH ALWAYS STRUGGLED FOR CRITICAL ACCEPTANCE, EVEN AS HE ACHIEVED FAME AND POPULARITY. HAS JAMIE’S WORK SUFFERED FROM SOME OF THE SAME CRITICISM THAT ANDREW’S DID?

When Jamie had his first show at Knoedler, when he was 20, Lincoln Kirstein, an important mentor, wrote the exhibition preface and described him as the greatest portraitist since John Singer Sargent. That may have rankled the critics. Andrew got flogged by the critics, who favored Abstract Expressionism or conceptual art, and I do think Jamie has suffered from some of the same criticism.

HOW WOULD YOU DESCRIBE JAMIE’S IMMERSIVE APPROACH TO PORTRAITURE?

It’s a long-distilling process that a number of artists have used. Lincoln Kirstein posed for him for 165 hours. Jamie said the Kennedy portrait scared the hell out of him because he didn’t have the sitter. So he asked for access to his brothers as a way to discern the family gestures and to inject some life into what he was gathering on the basis of photographs and newsreels of the late president. It was Teddy Kennedy who displayed that gesture of thinking with his head on his fist, one eye focused on the middle distance, one on the far distance, and weighing out his options. When the portrait was finished, Jackie thought it was wonderful and a great likeness of her husband, but it reminded Bobby too much of his brother struggling through the Bay of Pigs crisis. So Jamie kept the portrait.

In the exhibition, we’ll have several studies he did for the Kennedy portrait, as well as some of the many sketches leading up to the creation of the 1976 Warhol portrait. He portrays Warhol again from memory, in 2005 and then in 2009, based on the immersive experience that occurred earlier. After the Factory portrait exchange between Jamie and Warhol, Jamie worked with Rudolf Nureyev, who agreed to let him follow him around for 18 months. With Nureyev, too, Jamie came back and portrayed him after his death in 1993.

Profile with Black Wash (Study #23), of dancer Rudolf Nureyev, 1977

THE SHOW BRINGS TOGETHER THREE RECENT PANORAMIC CANVASES THAT SHOW FIGURES STANDING ON THE HEADLANDS OF MAINE’S MONHEGAN ISLAND, FACING OUT TO THE TURBULENT SEA.

After his father died in 2009, Jamie had this recurring dream of his artistic mentors on Monhegan. On the far left is Warhol, in the middle is Winslow Homer and then N.C. and Andrew are to the right looking out. The next one in the series is minus Homer, and the next one just has the Wyeths. That, for me, is very cinemagraphic. Those three works have never been seen together.

HOW MIGHT YOU INTERPRET THE DREAM?

It feels like a little bit of closure. He’s put the father and the grandfather in a greater context, as though to say, “Now I’m the one stretching out the seascape in front of you. Now it’s my time.”