April 17, 2022When journalists and vintage dealers started calling François Touret back in 2015, he was surprised. They were inquiring about the furniture created by the collective Les Artisans de Marolles (the Craftsmen of Marolles), founded by his father, Jean, in 1950 and named for the small village in France’s Loire Valley where it was based.

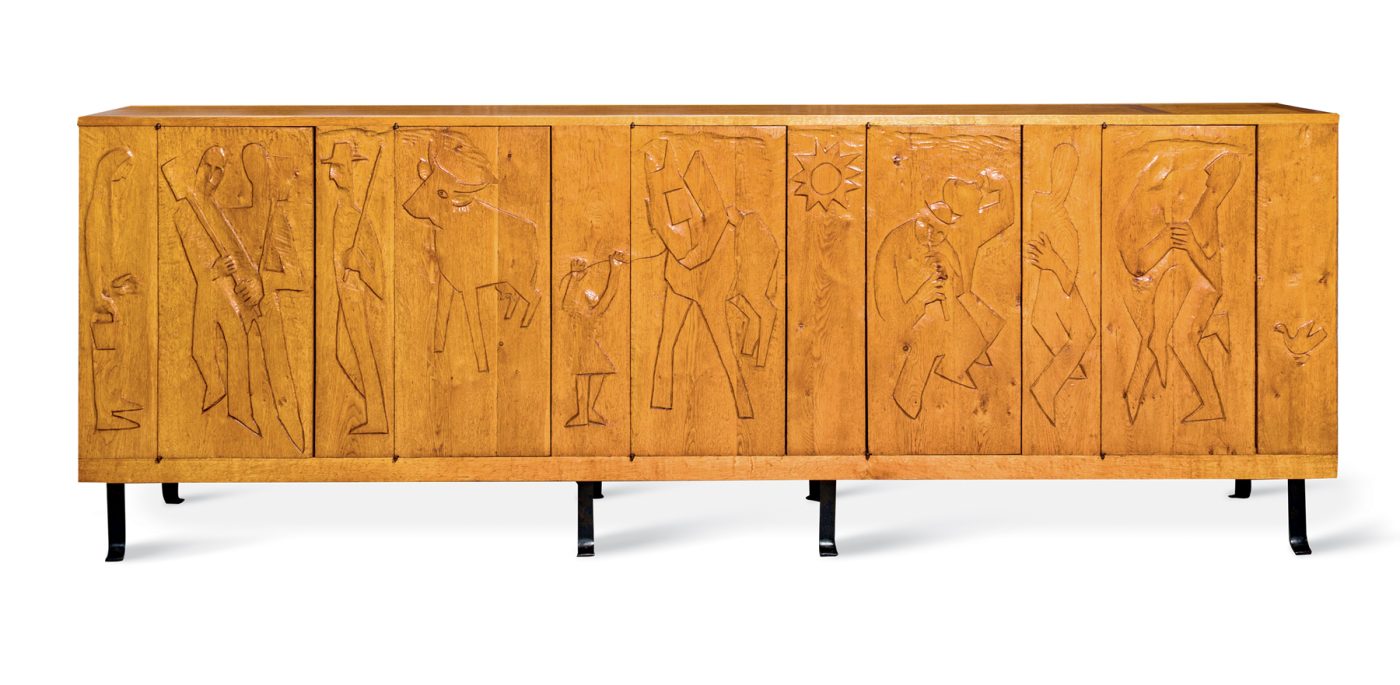

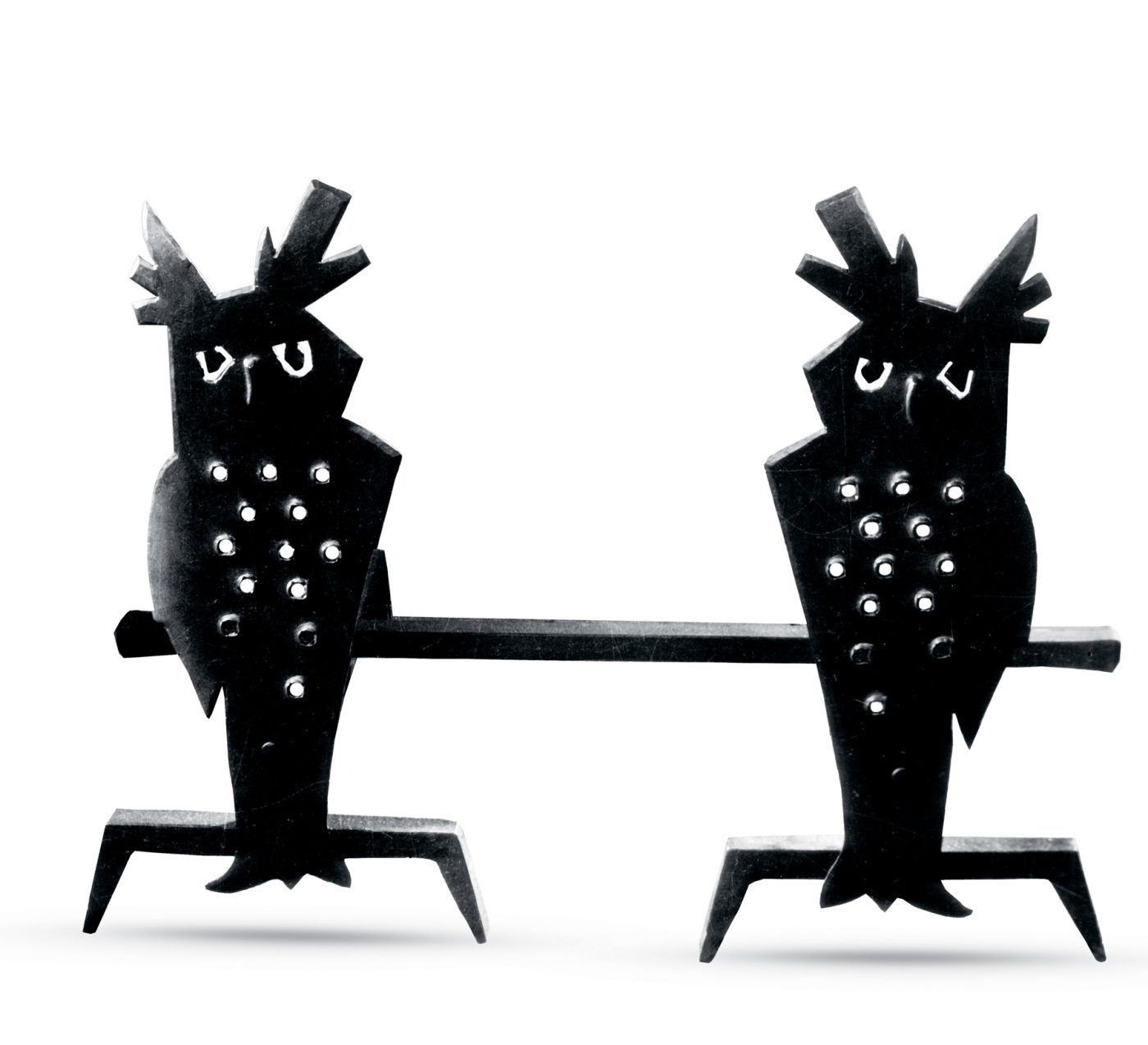

The rustic but exquisitely proportioned pieces included benches made from gouged wood, a wrought-iron sconce in the form of a cockerel, three-legged stools with seats carved to hug the body and a series of exceptional credenzas whose doors were sculpted by Jean Touret himself, with themes like the seven deadly sins and pastoral life.

“For me, this furniture . . . was banal and part of my daily life,” François recounts in Jean Touret, a bilingual monograph put together by Marie Kalt, former editor in chief of Architectural Digest France, and released in March by Paris-based publisher Les Éditions de l’Amateur, where Kalt is now editorial director. “Our family home was furnished with draft versions and prototypes.”

The work had been forgotten for decades. Its rediscovery is largely due to dealers like Benoist F. Drut, at Maison Gerard in New York, and Yves and Victor Gastou, in Paris, who were attracted to its elemental forms and handcrafted spirit. “I love its very casual, more country feel,” enthuses Drut. “It’s very simple in a way but very sophisticated in another.”

“There’s something very genuine about it,” concurs Victor Gastou, who runs the gallery founded by his late father in 1985. “It’s not at all fancy. Jean Touret had a real sense of beauty and poetry.”

Touret’s talents were not deployed only on tables and lamps. From the mid-1960s until shortly before his death, in 2004, he earned his living largely through ecclesiastical commissions, the most famous of which was the altarpiece at Notre-Dame de Paris. Installed in 1989 and destroyed in the fire that swept through the cathedral in 2019, the work consisted of a brass chest clad with bronze panels depicting the evangelists and the four great prophets.

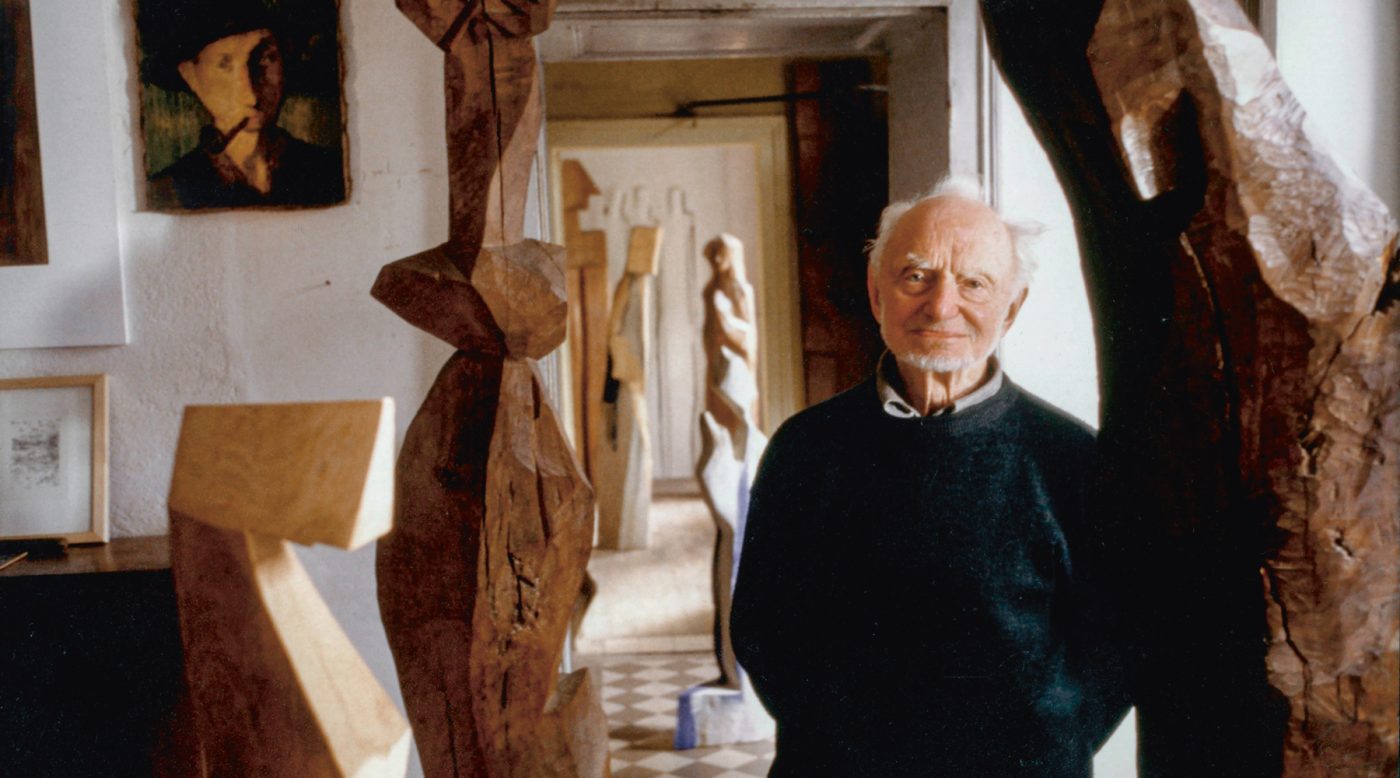

More than anything, Touret was a sculptor, although a rather unsuccessful one during his lifetime. He rarely exhibited, sold next to nothing and was never able to afford a heated studio. “His work passed everyone by,” notes Kalt. “Except for a few articles in local newspapers, there was not one art critic who took an interest in it.”

An exhibition at the Galerie Gastou, which runs until April 30, is meant to posthumously shed light on the work. On display is a series of towering, totem-like sculptures made from wood, as well as oak bas-reliefs and embossed metal panels. In one way or another, the majority depict slightly abstract human forms. “His work as a sculptor is exceptional,” says Victor Gastou. “It’s primitive and also a little Cubist in the vein of Ossip Zadkine.”

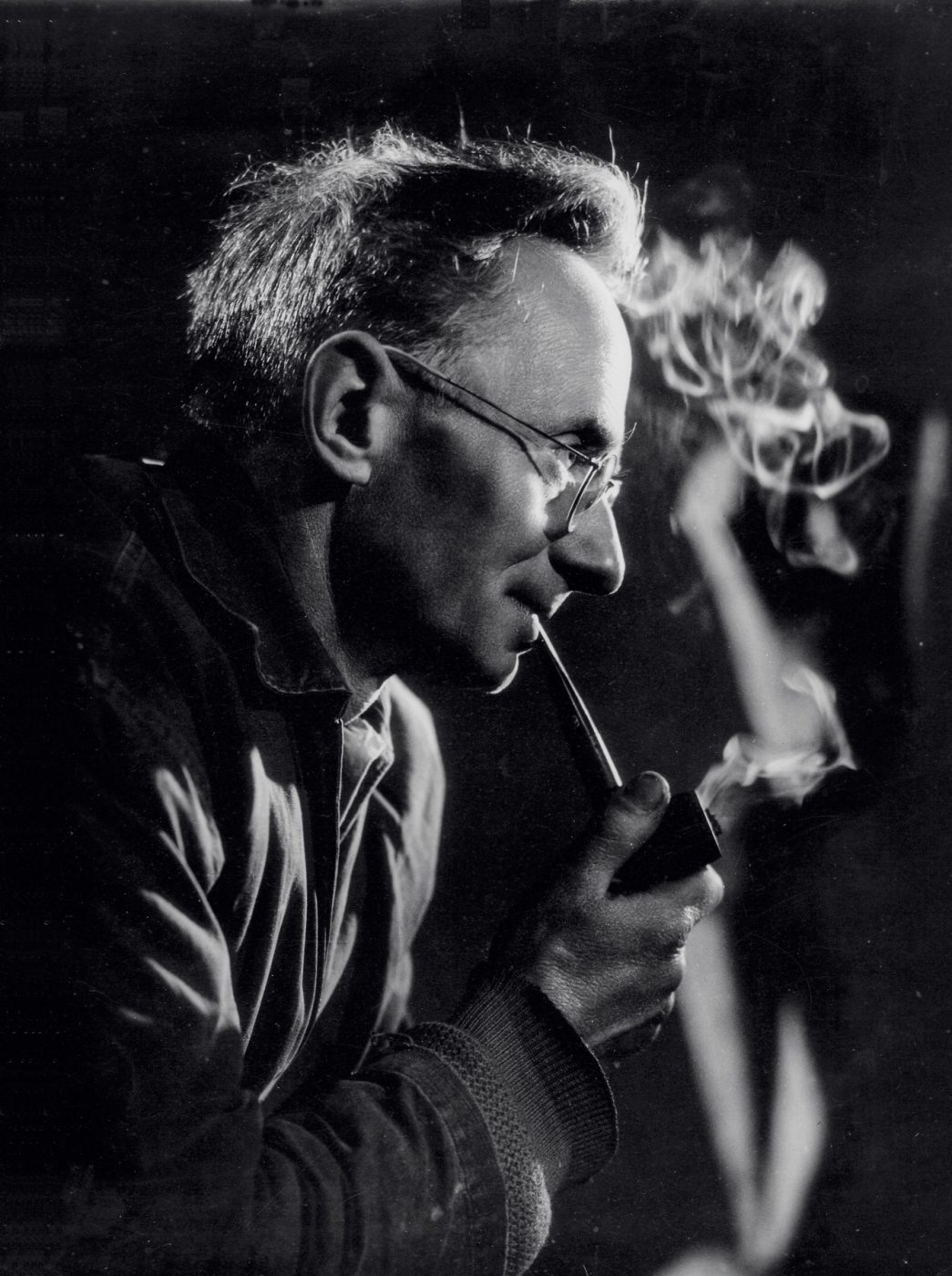

Touret was born in 1916 and largely brought up in Le Mans, in western France. His father died from a heart attack in 1926, and thereafter, his mother supported the family as a seamstress. Touret worked in the legal department of a local insurance company before fighting in World War II, during which he spent five years as a prisoner of war on the German–Czechoslovakian border. There, he had his first real contact with wood while being forced to work as a lumberjack.

At the end of hostilities, he returned to France, settled in Marolles with his wife, Odile, and declared that he would become an artist (he had previously taken evening classes with a painter in Le Mans). In 1950, the manager of the Château de Chambord commissioned him to create a number of sculptures of deer and wild boars for the pavilions in the château’s park.

That same year, Touret established Les Artisans de Marolles. For him, it was more a social venture than an artistic one. As industrialization expanded in postwar France, the village’s craftsmen found themselves in need of work.

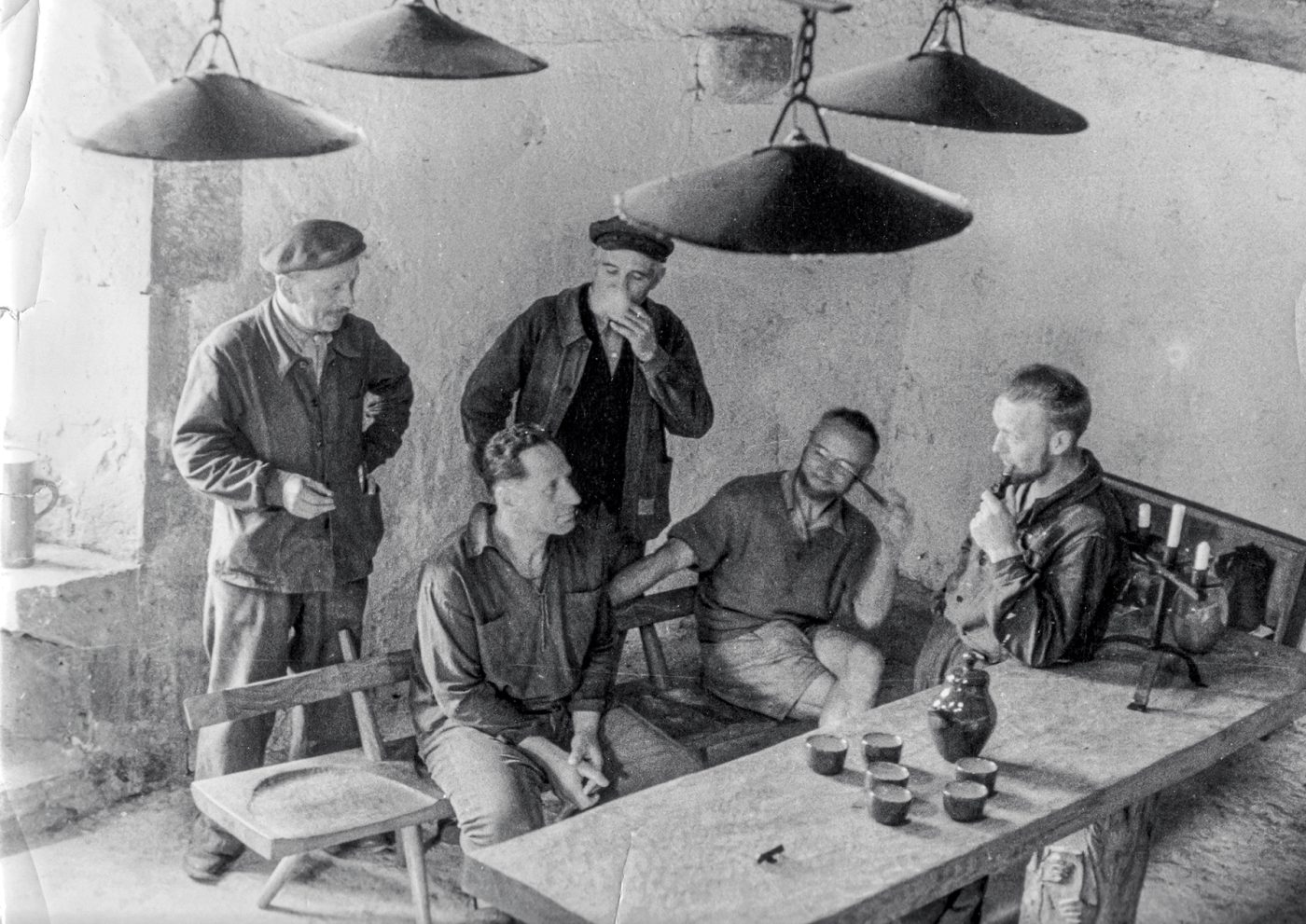

“What interested him was to find a destiny for those who no longer had a place in society,” notes François Touret. “He wasn’t really interested in either furniture or design.” The collective’s founding members were a basket maker, a potter, a blacksmith and a carpenter. The last, Émile Leroy, continued his work as a coffin maker while participating in the group. Apart from sculpting the credenza doors, Touret acted as artistic director, imposing his aesthetic vision through direct discussions with the craftsmen in their workshops rather than through drawings.

The first object produced was a simple wrought-iron candleholder with three spikes. Over the years, the collective’s output was regularly exhibited in both the Marolles village hall and the more magnificent setting of the nearby Château Royal de Blois. Certain items were also stocked by the Primavera boutique in Paris, an offshoot of the department store Le Printemps.

The group’s success was ultimately responsible for its downfall. To respond to the increasing demand, craftsmen from other villages were brought in, and as their numbers rose, so did tensions and disputes. Uninterested in ego management, Touret increasingly took a back seat, moving to a village on the other bank of the Loire in 1963 before officially quitting the following year. Although Les Artisans de Marolles continued to exist until 1970, the aesthetic quality of its production took a marked turn for the worse.

As for Touret, he stopped creating secular furniture altogether. In 1965, he met a young chaplain at the Sorbonne, Jean-Marie Lustiger, who went on to become not only his most indefatigable supporter but also a cardinal and the archbishop of Paris. It was Lustiger who initiated most of Touret’s commissions for the Church, whether monumental sculptures of Christ, liturgical furniture or the Notre-Dame de Paris altarpiece. “He wanted to help . . . show the invisible in the visible,” Lustiger once wrote of Touret.

Touret himself was an extremely religious man. Another of his sons, Sébastien, who assisted him from the early 1970s onward, recalls him regularly reading the Bible. “For him,” Sébastien remarks, “all his work was sacred.” Touret’s belief in God was matched by an undying faith in the virtue of both craftsmanship and simplicity. “A work of art that will move people until the end of the world,” he once told a journalist, “is one that produces the maximum amount of expressivity with a minimum of means.”