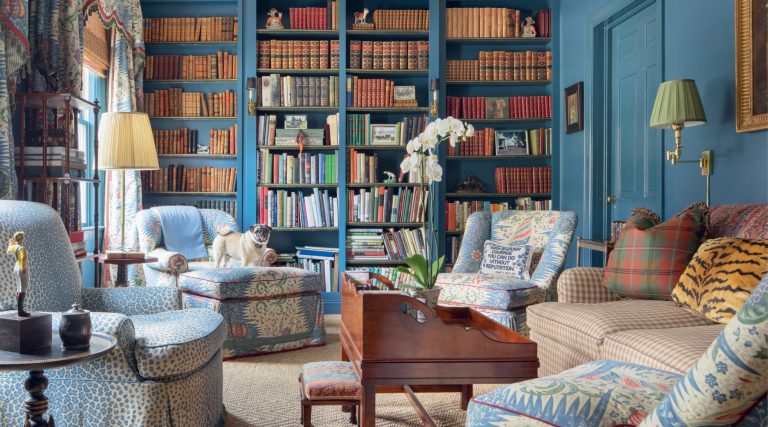

October 19, 2015“I relish my responsibilities as an alpha dog,” says the New York decorator Jeffrey Bilhuber, who has just released a new book. “What most people want is to be told what to do.” Top: A Palm Beach living room featuring a nontraditional plan, with the larger furnishings tucked into corners. All photos by William Abranowicz and courtesy of Rizzoli

Jeffrey Bilhuber has been working his particular brand of decorating magic for three decades. The New York designer is fluent in many stylistic idioms, but he is particularly adept at the kind of traditionalism that looks deadly serious until you spot the irreverent, expertly placed touches, like a stuffed peacock or a sculpture by the contemporary artist Chuck Price that sits atop a carved and gilded 17th-century bracket. Consistent throughout his work is a sense of glamour; even a cottage in the country seems to have been only recently vacated by Katharine Hepburn in her Bringing Up Baby days. It’s no wonder that celebrities (David Bowie and Iman, Mariska Hargitay) and stars of the creative world (Elsa Peretti, Hubert de Givenchy, Anna Wintour) seek him out to, as he writes in Jeffrey Bilhuber: American Master (Rizzoli), “spin whatever you put in front of me into something much more glorious than you ever imagined without me!” The title may be immodest, but the contents deliver. With a text by Sara Ruffin Costello and photographs by William Abranowicz, the book — Bilhuber’s fourth in 12 years — presents a mere eight interiors, but it goes deep into the ideas, materials, color choices and furnishings of each one.

After a glowing foreword by Hargitay — “At the end of each project, you get the best version not of him, but of YOU,” she writes — and an introduction by Bilhuber himself, the reader is immersed in his creative process. The pages are peppered with pithy pull quotes: “You’re only as good as your client,” or “Modernity is not about a new material; it’s about how you navigate your way through the world,” or “What’s liberating is to be fearless.”

The living room of a period Manhattan townhouse glows in egg-yolk-colored lacquer. Bilhuber turned tradition on its head here, too, upholstering the outside of the bergères in a traditional cotton floral, then doing the interior cushions in leather. Originally big enough for a palace, the 1930s Spanish carpet was cut down to fit from wall to wall.

And fearlessness is what comes across in these rooms. Bilhuber makes a stone farmhouse in Connecticut utterly modern by clever manipulations of scale and ruthless editing. His own Manhattan apartment is a lesson in the aforementioned tradition with a twist; that peacock is in his master bedroom, where it gazes into an oyster-shell mirror by Eve Kaplan that hangs on a wall covered in de Gournay paper. The living room of a New York townhouse is lacquered a brilliant egg-yolk yellow that makes the narrow space glow. (Lacquered walls seem to be all the rage these days, but they’re seldom handled with this level of skill.) Likewise, the picture gallery of an Elizabethan-style house in San Francisco is given the kind of treatment — fuchsia damask-covered walls, cheetah-print carpeting and console tables with boldly patterned and fringed skirts — that in lesser hands would cause vertigo.

But then Bilhuber is nothing if not supremely confident. “I relish my responsibilities as an alpha dog,” he recently told me. “What most people want is to be told what to do.” That is true even when they think they don’t, as in Hargitay’s recollection of the time she and her husband visited their house before it was completed — going against Bilhuber’s advice. They were horrified by what they saw then, but delighted by what greeted them two weeks later. The moral of the story, says Hargitay: “Don’t peek over a master’s shoulder while he is still working!”

In the central picture gallery of an Elizabethan-style residence in San Francisco, Bilhuber covered the walls in fuchsia damask and the floors in a cheetah-print carpet. Photos, paintings and mirrors in gilt frames hang on the walls almost from ceiling to floor.

Similarly, the book recounts a visit Wintour insisted on making on her own to look at lamps. The Vogue editor — a repeat client who wrote the introduction to the designer’s first book, Jeffrey Bilhuber’s Design Basics — ended up fleeing, overwhelmed by too many choices, before conceding that perhaps it was better to look at a smaller selection that had been narrowed down by a pro. “Our biggest job,” Bilhuber told me, “is to edit.”

Now that this book is out, it’s a fair bet that the designer will be gearing up for the next one. Perhaps it will feature some of the projects on which he is currently at work, like the house in Marfa, Texas, for the advertising executive Trey Laird and his wife, Jenny (Annabelle Selldorf is the architect, and Madison Cox the garden designer) or a house on the 19th-century streetscape of Elgin Crescent in London. More projects, more stories to tell and more wittily phrased wisdom to impart. “I love an audience,” Bilhuber assured me. “I’m a great speaker, a wonderful communicator. I’m an educator — I like to share information.”

We’ll be all ears — and eyes.

On Monday, October 26, Bilhuber will be signing copies of his book at the International Show, the annual New York art and antiques fair at the Park Avenue Armory, from 5:30 to 7:30 p.m. Ten percent of the proceeds will be donated to the Fund for Park Avenue.