A new book from the Monacelli Press provides insight into the work of Manhattan-based architect John B. Murray. Above: In a home on New York’s Central Park whose interiors are by Tammy Connor, Murray used a deep plaster cornice to add intimacy and hide mechanical systems (photo by Simon Upton). Top: The living room of a Murray-designed East Hampton house whose decor is by Victoria Hagan (photo by Durston Saylor).

September 23, 2018We’ve come to expect a coffee-table design book to have full-bleed photographs of high-end homes, elegant furniture and objects and smart architectural details. We don’t necessarily expect schematic drawings, especially ones with a beguiling French name: analytique.

Analytiques are exactly what we find, however, in John B. Murray’s Contemporary Classical Architecture (Monacelli Press). Each project features one of these elevation drawings, laid out right up front, along with other key drawings, so that we are dazzled not only by surfaces (which have been artfully supplied by some of the leading lights of interior design) but by the conceptual framework of the architecture, as well.

“It distills things,” the affable, New York–based Murray says of his approach. In one chapter, about a grand apartment on Manhattan’s Fifth Avenue — made even grander with glamorous touches by Tony Ingrao and Randy Kemper, of Ingrao Inc. — we see how Murray reformatted the plan so that the key spaces gained exposure to Central Park. This entailed, in one case, turning a master bathroom into a library. (The home’s setting, in a historic limestone building by Emery Roth, didn’t hurt the overall effect.)

A schematic drawing known as an analytique — like this one, created for a pied-à-terre on New York’s Park Avenue — accompanies the text and photographs for each of the 15 projects featured in the book. The specific architectural information these convey helps readers understand Murray’s thinking and process.

The term distillation could be applied to Murray’s architecture generally, which, as the book’s title suggests, boils down lessons of the past and presents them in a fresh and relevant way. Perusing the 15 homes featured here — several of which, like that Fifth Avenue apartment, look out over Central Park from within storied prewar buildings — it’s not surprising that Murray got his start at the famed firm Parish-Hadley, as so many current top talents did. “In a lot of ways, it defined where I was going to be going,” he says. “I was developing a practice that had roots in tradition, not in fashion. I loved that aspect of being there. It was refreshing, and in some ways radical.”

One illustrious former Parish-Hadley colleague, Bunny Williams, wrote the foreword to the new monograph. In it, she states, “Whether John is restoring an old house, redesigning an awkward apartment or creating a house from the ground up, one always has the sense that this is the way it should have always been.”

Murray hails from Philadelphia and was educated at Carnegie Mellon University, in Pittsburgh. He has led his own firm for 21 years and now has some 20 associates in his office. He remains proudly out of step with the trends. “It’s too strong to say we’re renegades, but we’re at one end of the field,” he says. “I look now at the work of John Russell Pope, for instance, and I think it feels very contemporary in its own right. There’s a sense of reserve that can be shockingly modern, in a way.”

Murray has applied his somewhat heterodox approach to residences up and down the Eastern seaboard, including a 6,200-square-foot duplex overlooking Central Park in an Arts and Crafts building designed by Henry Wilhelm Wilkinson. Here, Murray had the task of combining several smaller apartments, so a complete rethinking of the plan was required. Among other revisions, his team ripped out a tiny spiral stair to create a vast entrance hall with a majestic sets of steps. “It organized everything vertically,” the architect says simply.

Working in a landmarked building on New York’s Fifth Avenue, Murray joined two apartments to create a single, grand, full-floor home. Here, the combined residence’s long enfilade shows off interiors designed by Cullman & Kravis. Photo by Nick Johnson

In the process, it also created “a room which was in a sense landlocked within the plan of the building,” he adds, meaning that this second-floor area was one of the few without an exposure. “So we activated that space by making it an alcove off the stair hall, and it became the billiard room.”

The project benefited from the talents of interior designer Stephen Sills (Murray’s firm usually hands off decorating duties). Sills paneled the newly created billiard room, with its coved ceiling, in stained oak for maximum coziness and applied a special finish to the walls of the marquee stair hall nearby. “It’s very subtle, but the rustication in the plaster work over this whole huge area was such a beautiful treatment, and it shows Stephen’s sensibility,” Murray says. Ditto a firewood storage box made of gleaming copper that was set into one wall of the living room, giving the view outside a run for its money.

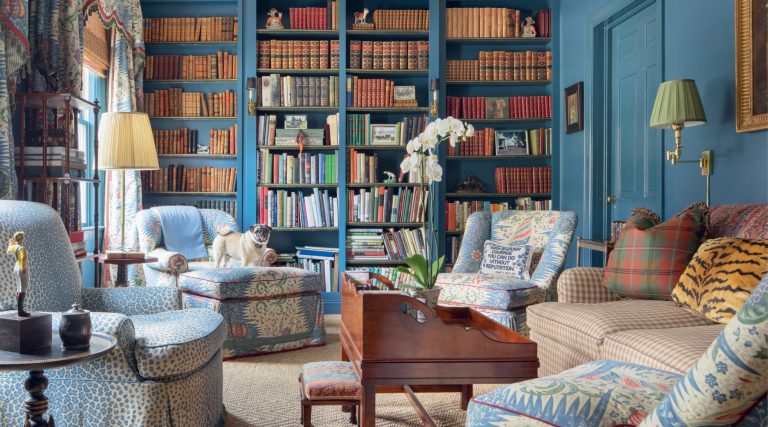

Murray collaborated on another Central Park showplace, this one in a 1938 building by A. Rollin Caughey and William F. Evans Jr., with Charleston, South Carolina–based interiors ace Tammy Connor. Connor made contributions like commissioning a park-themed mural for the lower gallery, which Murray was very on board with. “One thing that makes the process work so well is that he’s super-knowledgeable, but there’s no ego,” Connor says of Murray. She sourced quite a few key furnishings for the project from 1stdibs, including a late Regency tub chair for that same space.

In addition to materials from a 1780s New Jersey structure, an Upstate New York barn incorporates a threshing floor salvaged from a 19th-century Pennsylvania barn. The completed building serves multiple purposes, from living room to concert hall, yoga studio to game room. Photo by Pieter Estersohn

It was relatively easy for designer and architect to get, and stay, on the same page. “Conceptually, the conversation was how to bring the outside in,” Connor says of their shared goal. She was skeptical, however — at least at first — about Murray’s bold plan to remove the terrace’s elegant, if well-worn balustrade (which was partly rotted) and replace it with glass panels edged in bronze. “I was nervous,” she says, “but he was so right.” The clients can now see clear through to the greenery.

For a Park Avenue apartment in a 1916 building designed by J. E. R. Carpenter — as close to a perfect blue-chip pedigree as you can get — Murray had the advantage of lofty, 11-foot ceilings, and he removed everything down to the studs to start anew with the space. Working on the interiors with David Kleinberg, a colleague from Parish-Hadley, made things easy, Murray says, “as we have a shared language.”

“A classic perspective shows an appreciation for the artistry of the past or the classic simplicity of the forms,” Murray writes in the book’s introduction. He goes on to note that the homes included in the volume “show that layers of classic architectural framing and complex problem-solving are for the here and the now.” Photo by Francesco Lagnese

He jiggered the floor plan so that the entry hall leads right into the dining room, with the living room off to the right. This created axes from which to view the clients’ estimable art collection, including pieces by John Chamberlain and Vik Muniz. Among the most pored-over elements was a scalloped cornice detail, which ended up as one of the most distinct, elegant aspects of the design. It’s not clear whether it’s old or new, and that’s very much the point.

Even after a half-century of existence, televisions remain in the “Necessary Evil” category for architects and designers, who talk a lot about the challenges of artfully incorporating them in living spaces. For this apartment, Murray asked himself, “How can you conceal a television but also reveal it?” The answer he came up with was a snazzy, rectangular divided mirror surrounded by a nickel band. The two halves pull apart to unveil the screen. “They have their own beauty,” he adds, and an enhanced one, because he also expanded the small fireplace below with a nickel surround; otherwise the proportions would have been off when compared with the mirror above.

That trick — in its attention to harmony and balance, but also its forthright incorporation of how people live today — is echt Murray. For more of that, dig into the rest of the new book.