(photo by Yoichi R. Okamoto). Top: Running through June 19, a major retrospective at Vienna’s Museum of Applied Arts (MAK) titled “Progress Through Beauty” presents more than a thousand of his creations.

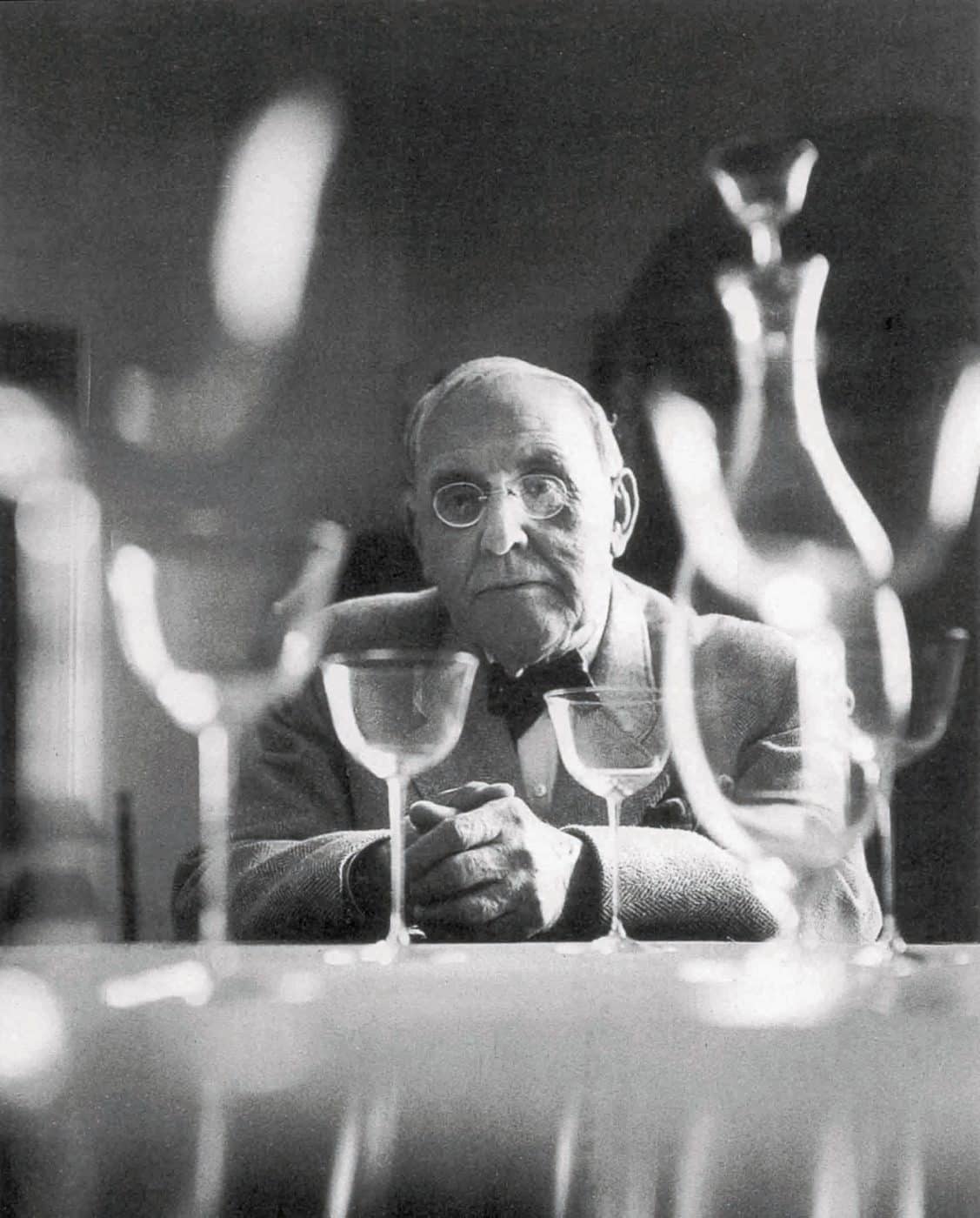

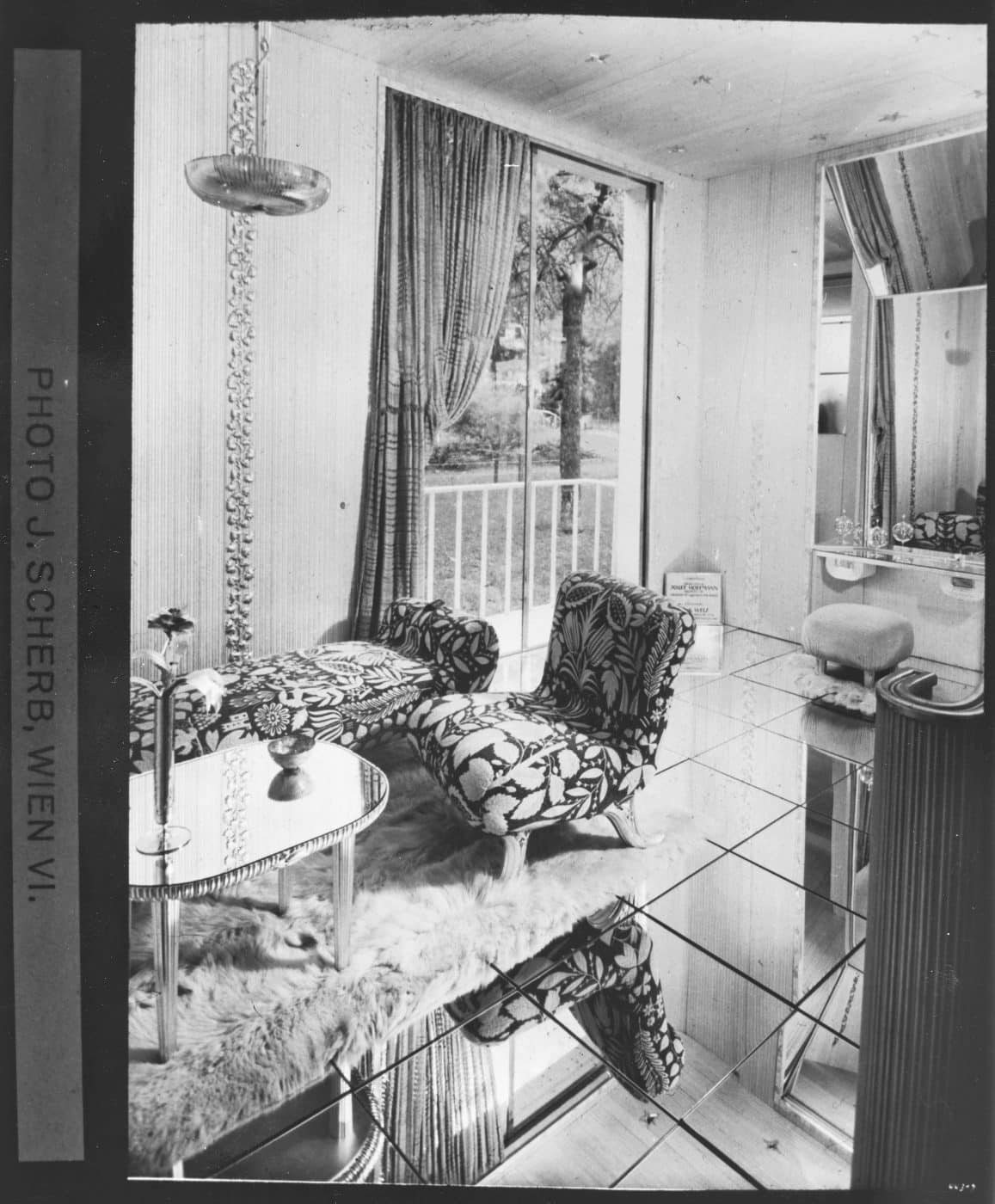

May 15, 2022At the end of May 1956, a short notice of the death in Vienna of Josef Hoffmann at the age of 85 appeared in the New York Times. The paper might not have printed an obituary of Hoffmann, one of the 20th century’s greatest design talents, at all had the newsroom not been contacted by a former student and assistant of his, Leopold Kleiner. At the end of Hoffmann’s life, his reputation had almost entirely faded. The Times merely recorded that he was “a pioneer in modern architecture and design” and a “founder and leader for thirty years of the Wiener Werkstaette [sic], a famous artcraft center.” No mention was made of his significance for American modernism, to which this once-influential Viennese had made a formative contribution, whether through his straightforward design for the Louisiana Purchase Exposition in 1904 or his legendary powder room at the International Exposition of Art in Industry held at Macy’s department store in New York in May 1928. The virtuosity of his play with glass, mirrors and chromed metals on the floor, walls and ceiling was such that visitors could see themselves in 10 different reflections. On this occasion, a reporter for the Times expressed considerably greater enthusiasm about Hoffmann, writing, “Yesterday afternoon the crowds in front of this room had to be held back.” From being a sensation to being forgotten — and back again: Nearly a century on, Vienna’s Museum of Applied Arts (MAK) is reevaluating Hoffmann’s importance.

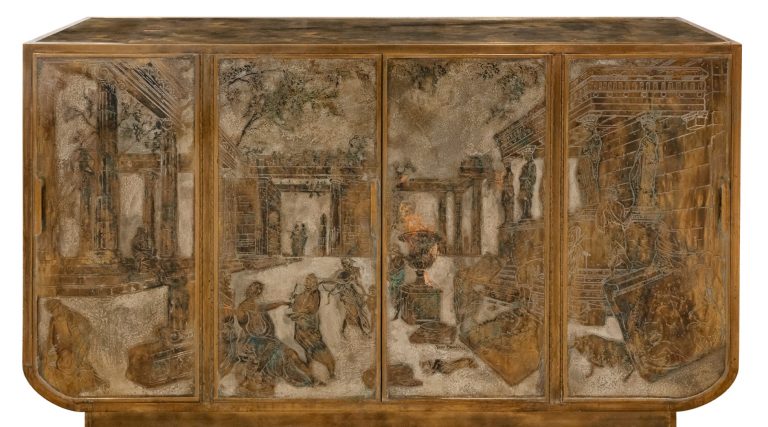

The most comprehensive retrospective to date of his impressive oeuvre, the MAK’s “Progress Through Beauty” exhibition honors the architect, designer (of iconic furniture, lighting, decorative objects and fashion), teacher and exhibition maker, who was one of the key figures in Viennese design from the late 1890s on. Bringing beauty to the lives of his clients was for him synonymous with aesthetic and social progress. Hoffmann did not accept any distinction between high and low art. His brilliance is encapsulated in more than 1,000 objects, such as a table he created for the living room of Dr. Hans Salzer’s apartment, circa 1902; a set of silver flatware manufactured by the Wiener Werkstätte for Fritz and Lili Waerndorfer; and the daybed, upholstered in an exquisite plant-motif fabric, from the Boudoir for a Big Star that he designed for the Paris International Exhibition in 1937. The show also includes several previously unknown works, thus filling important gaps in research. In 20 different sections, it explores Hoffmann’s enormous body of work, encompassing all aspects of daily life.

“It was a stroke of luck that the exhibition had to be postponed by a year,” says MAK curator Rainald Franz, one of the show’s organizers, “because previously unknown items emerged from private collections.” These include Hoffmann’s silver tableware for Sonja Knips (a Viennese industrialist’s wife who was famously painted by Klimt), furniture for the Wittgenstein family and, Franz’s especial pride, plans and photographs, previously thought to be lost, of Hoffmann’s Austrian Pavilion at the Paris World Exposition in 1925.

Following this discovery, Franz commissioned specialists in modeling and ceramics to make a 1-to-20-scale architectural reproduction that “enables the ephemeral building to be experienced once again as an idea and a space.” “In contrast to International Modernism, Hoffmann was the master of ‘pattern modernism,’ ” says Franz, because he always knew how to flatter his clients with ornaments in order to win them over to his modernist approach.

Josef Franz Maria Hoffmann was born in 1870, the third of six children, in the small town of Pirnitz, in Moravia, a region of what is now the Czech Republic. His father Josef Franz Karl was co-owner of a local textile factory and also the town’s mayor. The tradition of Moravian folk art, the fertile countryside and a rather cosseted bourgeois family life were the pillars of a childhood that decisively shaped Hoffmann’s later life, as he recorded in his autobiography.

In 1892, he entered the Special School of Architecture at the Akademie der bildenden Künste (Academy of Fine Arts) in Vienna. There, he studied under Otto Wagner, who revolutionized the establishment’s teaching in part by posing progressive questions about emerging metropolises. Hoffmann later repeatedly referred to Wagner’s influence on his work and throughout his life remained a great admirer of his teacher, on whose recommendation he was appointed professor at the Wiener Kunstgewerbeschule (Vienna School of Applied Arts). Hoffmann created his first major colony of villas, in Vienna’s Hohe Warte district, holistically rather than as discrete individual designs, with the aim of achieving an overrarching unity among the architecture, interiors and gardens. Common features included double-height central living rooms, palettes of sharply contrasting colors and an extensive use of grid patterns, on floors, wall paneling and windows.

Hoffmann’s new symbiosis caught the attention of a young Belgian couple, the magnate Adolphe Stoclet and his wife, Suzanne Stoclet-Stevens. At once, they entrusted him with what was to be his major architectural work: the three-story Palais Stoclet, in Brussels. Hoffmann designed not only the main residence, lavishly clad in slabs of marble and famously featuring a monumental sculptural tower topped by four muscular male figures, but also the whole of the interior, all of the gardens and the ancillary buildings. In accordance with the concept of Gesamtkunstwerk, Hoffmann commissioned various artists to work on the palace, including Klimt (the mosaic frieze in the dining room), George Minne (the marble fountain), Carl Otto Czeschka (the window glass), Michael Powolny (ceramics) and Franz Metzner (sculptures), contributing to galloping building costs that got out of hand even for the Stoclets.

During this period, Hoffmann was working on his magnum opus of furniture design: the Sitzmaschine (literally “machine for sitting”) chair, created for the sanatorium in Purkersdorf, near Vienna, one of the Wiener Werkstätte’s first commissions. An example is currently on offer at JF Chen in Los Angeles, which frequently handles Hoffmann material. “I’m particularly intrigued by the first decade of the twentieth century, when J. & J. Kohn was fabricating furniture for Josef Hoffmann,” says Bianca Chen, the gallery’s managing director. “The degree of fluidness, the bentwood and the high-gloss finishes they did at that time really appeal to me. His designs have a special place in our collection.”

Wolfgang Karolinsky, the director and founder of Woka Lamps Vienna, first came upon Hoffmann’s work at the city’s flea market as a music student in the 1970s. That discovery quickly led to a career in the decorative arts. “I set up a photographic archive with five thousand images of his creations arranged by product group,” Karolinsky explains. (There are thought to be 10,000 to 15,000 Hoffmann designs in total.) He also started to restore Hoffmann lamps he collected. “Their design displays his sense of modernity,” Karolinsky says. “He had a love of circle and square shapes that had never been used before in applied or fine arts.” In 1977, Karolinsky opened his gallery in Vienna and a year later began selling reeditions of Hoffmann’s lighting designs. Today, he offers an extensive selection of them on 1stDibs, along with a smattering of the designer’s original furniture pieces, such as a rare bentwood Barrel chair dating to 1908.

Hoffmann’s lighting designs are in greater demand than ever. Several of Woka’s pieces illuminate The Goodtime Hotel, in Miami, owned by the singer and producer Pharrell Williams, as well as London’s Beaumont Hotel, and the firm’s clients range from Peter Marino to Ken Fulk. “Ninety-five percent of our turnover is exported abroad, mostly to America,” Karolinsky says.

An obituary of the master of the Gesamtkunstwerk would no doubt have a completely different tone today, for Hoffmann is back where he always belonged — at the very forefront of modernism.