March 6, 2022In 2008, fine-art photographer Karen Knorr set off for India for what she now describes as a “life-changing journey.” At the time, however, the artist had her reservations about going there.

“I’m a white European American,” says the Frankfurt, Germany–born, London-based Knorr. “I didn’t want to be seen as an artist who goes to India, uses the country’s cultural heritage to sell work in the West and gives nothing back to India.”

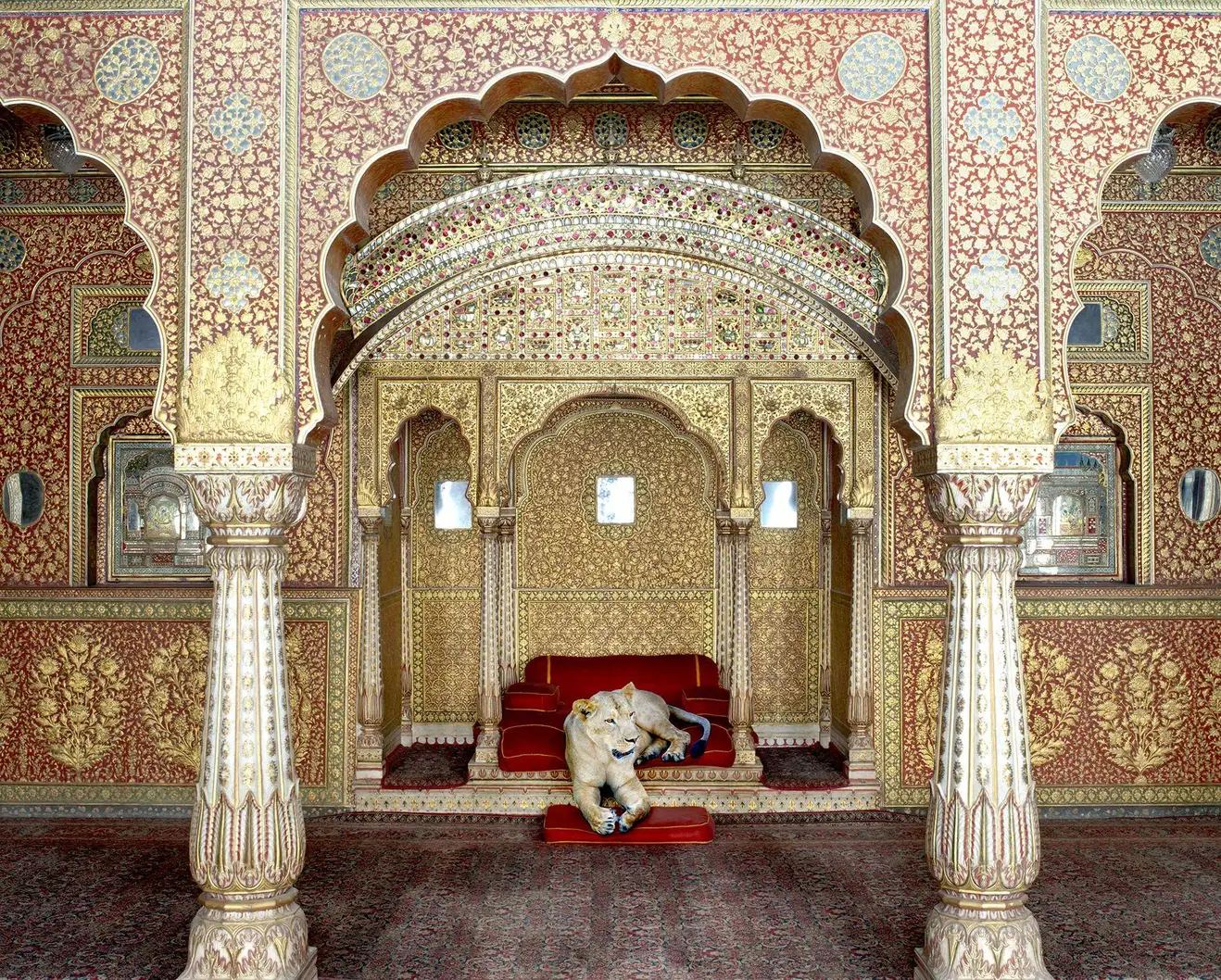

That journey, across 21 days, 2,000 miles and 17 different palaces, mausoleums and holy sites, led to an ongoing relationship with the country and “India Song,” a series that continues to this day of exquisite images that comment on the caste system, gender inequality and climate change. The photographs unite palace interiors with animals, the analog with the digital, magical realism with mythology, aesthetics with social critique.

“I’ve always had this funny contradiction in me. I love the study of aesthetics, philosophy, which are very elite subjects,” says Knorr, whose work is included in collections at Tate Modern, Centre Pompidou and the San Francisco Museum of Art, among many others. “But I’m also interested in doing work that is about change and critique. Somehow, I’ve managed to combine them both as I’ve gotten older.”

Pieces from the provocative series — in which animals such as Bengal tigers, lions and peacocks photographed in nature reserves and zoos with a digital camera have been photoshopped into the sublime interiors of Mughal and Rajput palaces photographed with a large-format analog camera — are now on display in several group shows. These include “Opening Doors,” the inaugural exhibition of Danziger Gallery’s new Los Angeles location; the all-female show “A Room of Her Own” at Sundaram Tagore Gallery in Singapore; and “Visions of India: From the Colonial to the Contemporary” at the Monash Gallery of Art, which marks the first major survey of Indian photography in Australia.

“Karen’s photographs literally stop people in their tracks,” says Sundaram Tagore. “It’s the unique combination of color, pattern and exoticism. And while sumptuous and playful, her work considers serious issues, including constructs of power and hierarchy rooted in cultural heritage.”

Knorr’s work, which spans from the 1970s until today and, in the words of gallerist James Danziger, attracts serious photography collectors and lovers of India for its “originality, vitality and strength,” is ultimately rooted in her own background.

Born in Germany to an American military family in 1954, the self-described “architecture photographer and wildlife photographer by accident,” was the child of adventurous, culturally minded parents. Both of her parents, Major Robert Knorr and Betty Luros, worked for Stars and Stripes magazine, for which her mother was a photojournalist and her father was an editor.

When Knorr was four, her family (including an older brother) moved to Puerto Rico where, taking advantage of “Operation Bootstrap,” the postwar program to develop and industrialize the island, her father launched a successful import-export business.

“I had a very carefree childhood. I lived five-hundred yards from the ocean. I would go swimming, and I would go shell collecting. I was a bit of a tomboy,” recalls Knorr, who arrived in Puerto Rico speaking German and English and quickly picked up Spanish. “It was a most idyllic childhood in the tropics. A childhood I could not offer my son in London [where she has resided since 1976], so I’m very aware of that privileged postwar moment.”

Knorr, who picked up her first camera at the age of nine, became acutely aware of her background when she went to the U.S. mainland to study what she calls “a humanities arts course, including French, German philosophy and photography” at the experimental Franconia College in New Hampshire. “I felt like a fish out of water,” she says. “Most of my peers didn’t have my sort of international background. So they were puzzled by me. And I took it a bit badly.”

Despite suffering socially at Franconia, Knorr says, “a whole new world opened up to me there.” She studied with photographer Eileen Cowen, whose narrative approach has had an influence on her work. “She was the first tutor who really encouraged my photography,” says Knorr.

Knorr went on to graduate from the Polytechnic of Central London (now the University of Westminster), following three years in Paris, where her acquired fluency of French would lead to her first major breakthrough.

“Because of my language skills, and also this confidence that you get coming from my particular class background, I went back to France after I graduated with this work called ‘Belgravia,’ ” she explains. “And I immediately got a solo show. It was reviewed favorably in Le Monde.”

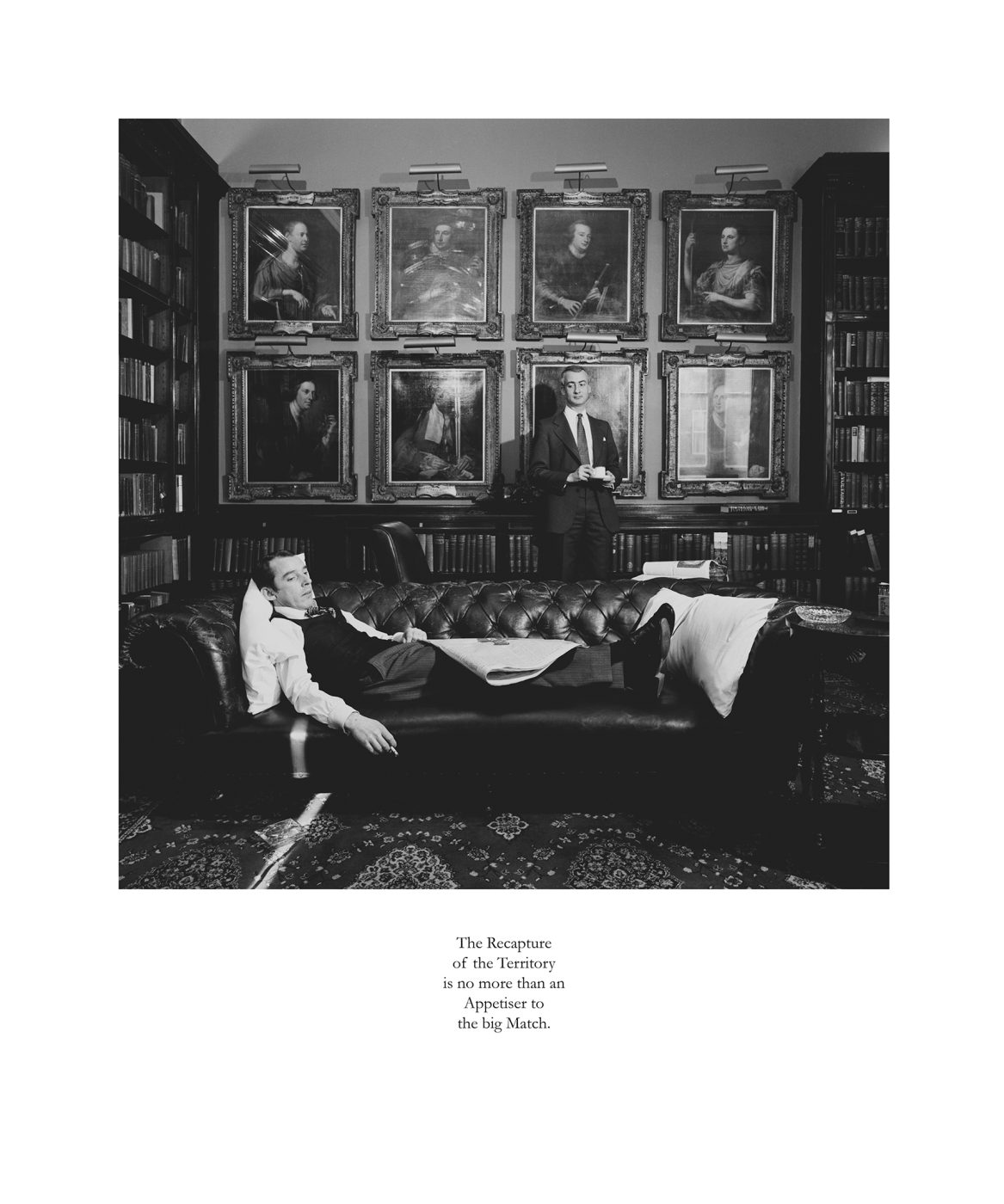

That wry 1979–81 series consists of staged black-and-white photos shot inside the domestic interiors of London’s affluent class, including Knorr’s own family, accompanied by ironic or deadpan text. For example, in one photograph of a distinguished couple posed in front of their fireplace and staring at the camera with remarkable self-possession, the text reads: “Today Security is more than a Luxury. It is an absolute Necessity.”

“Belgravia” was followed by one of Knorr’s best-known series, “Gentleman” (1981–83), which she created in a similar vein, although this time, the scenes take place in gentlemen’s clubs around London’s St. James’s district.

“From the very beginning, I was very interested in how environment and place reflected class identity, lifestyle or status,” says Knorr, who often uses text, titles or, as with “India Song,” beauty to slow down the viewer so they can take a more critical look at the work.

Subsequent projects, like “Connoisseurs and Academies,” explored ideas of art and aesthetics through staged images set inside museums and academies in Europe. But it was Knorr’s “Fables” (2003–8), a slightly eerie series of images of animals (also shot digitally) inside Western castles and other heritage sites (also shot analog), including Le Corbusier’s Villa Savoye, that caught the attention of prominent collector and art patron Abhishek Poddar, founder of the Museum of Art and Photography in Bengaluru.

“He asked me if I could do something similar in India,” she says. “Abhishek turned out to be probably one of the most important figures for me in India, helping me to make this work.”

In The Queen’s Room, Zanana, Udaipur City Palace (2010), a male peacock stands within the vivid green walls of a zanana (or woman’s space) of the Udaipur City Palace. As Knorr explored in “Gentleman,” the series considers how the rooms are gendered; in this case, traditional Indian palaces were divided into male (mardana) and female (zanana) quarters.

“India Song” also uses animals as disruptors, says Knorr, and as references to mythology and epic stories, as in Arjuna’s Path, Junha Mahal, Dungarpur (2014), where a tiger is seemingly on the prowl inside the frescoed Juna Mahal, a once royal residence. The vivid piece is featured in the Danziger Gallery’s show.

Now 68, Knorr, who has taught since the 1980s, is about to go on sabbatical from her professorship at the University of the Creative Arts in Farnham to organize her archive and estate, but she isn’t slowing down. “I’m just now, at this moment in time, trying to do as much as I can with new work,” she says, mentioning a recent addition to “India Song” and a personal project in Puerto Rico where she was about to head for a month.

“I’m also an advocate for women in photography,” she says, noting that this, along with climate change, is most important for her in her work today. “One of my most proud career moments was forming Fast Forward: Women in Photography.” It’s a research group at her university that helps emerging women photographers around the world through exhibitions, workshops and mentorship programs.

“Although I’ve always said I don’t want to do expressive personal work, the work has always been personal,” she says. “Funny how you try to get away from some things, but they keep coming back.”