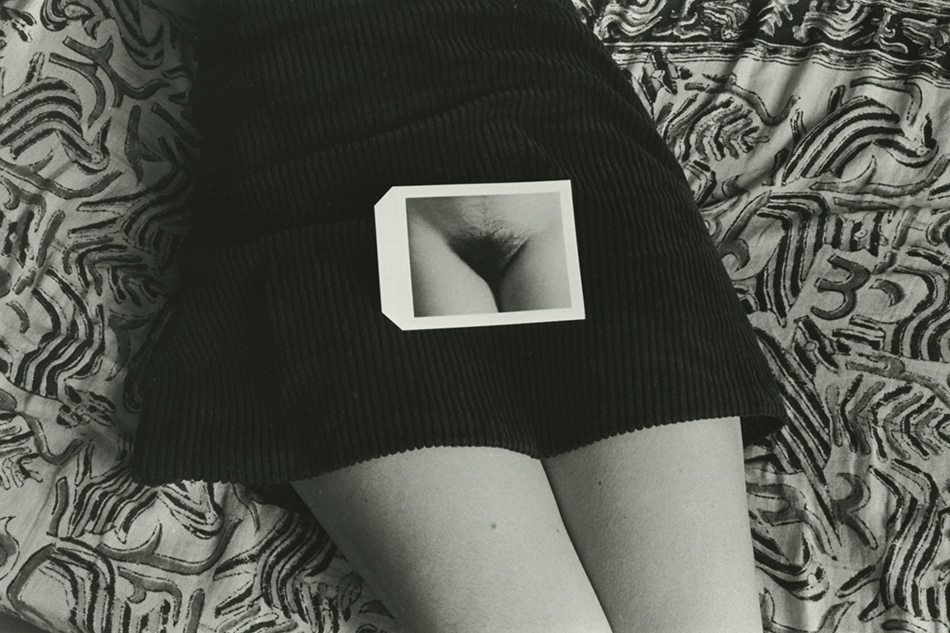

January 11, 2016Although he has worked with color photography, black and white remains Kenneth Josephson‘s palette of choice, as seen in Polapans, 1973, one of 61 pieces on view in the retrospective “Kenneth Josephson: Encounters with the Universe,” at the Denver Art Museum. Top: Wisconsin, 1964, also on view, shows his penchant for capturing objects found in nature and revealing their spirit. All photos © Kenneth Josephson, unless otherwise noted

The photographer Kenneth Josephson‘s most famous image is a stark black-and-white photograph of a lightbulb hanging above a series of Polaroids of the same bulb. Polapans (1973) is witty and abstract, a sort of picture-within-a-picture infinite recursion, calling into question the ability of photography to capture what’s real.

Polapans is on view with 61 other photographs at the Denver Art Museum until May as part of “Kenneth Josephson: Encounters with the Universe.” This is the largest museum show of the artist’s work since the major retrospective that opened in 1999 at the Art Institute of Chicago and ended in 2001 at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York.

In her New York Times review of the Whitney show, Vicki Goldberg called Josephson “one of the earliest and most inventive explorers of the medium’s character and the issues of perception and representation,” praising his “experiments, games and conundrums that dissect the medium with a persistently questioning spirit and an occasional sly smile.”

The Chicago-based Josephson is 83, a modest Midwestern fellow who isn’t particularly interested in taking a victory lap; he is spry and still works daily. “I surprise myself every day,” he jokes about the achievement of merely existing in his 80s. Such humor runs deep in his work, and he cites the dry absurdity of British comedian Peter Sellers as a touchstone. Josephson’s pictures within pictures include a series of nudes with photographs covering (or not covering) sensitive areas, sometimes creating surprising juxtapositions — a joke that in his hands isn’t dirty but thought provoking and wry.

Wyoming, 1971, is part of Josephson’s wry “History of Photography” series.

“I’m primarily interested in visual ideas,” Josephson says. “My work is mostly conceptual in style. I like to make references to the history of photography, the process or particular photographs.”

Although he has sometimes worked in color, Josephson prefers black-and-white photography and will always be known for it. “I like the strangeness of it,” he says. “My ideas seemed to work better in black and white. It’s more abstract.”

Josephson “has a terrific eye for things in the landscape and the world around us, and a way of capturing those and making a commentary that is both witty and meaningful,” says his New York dealer, Yancey Richardson.

The idea of having an “eye” might seem somewhat antiquated these days, but Josephson clearly has one. Some of the works in his series “Marks and Evidence” are simply images of tire tracks on pavement or ground; strikingly composed, they suggest the absence of the car that made them — and the people inside it. Matthew (1965) is just a picture of a child (Josephson’s son) in front of a brick wall, but he’d holding an upside-down photo of himself in front of his face and looks as if he were pressing the shutter of an imaginary camera.

Born in Detroit, Josephson enrolled in the photography program at the Rochester Institute of Technology in the early 1950s, but his studies were interrupted in 1953, when he was drafted into the army. After training at Fort Belvoir in Virginia, he was stationed in Kaiserslautern, Germany, where he applied his photographic skills to intelligence and maps-making. Upon his discharge in 1955, he returned to complete his studies at RIT.

“I’m primarily interested in visual ideas,” Josephson says. “I like to make references to the history of photography, the process or particular photographs.”

Chicago, 1959.

“I had never been to Europe,” he recalls of his time in Germany. “It had a very good effect on me.” While roaming around looking for things to take pictures of, the proverbial lightbulb went off: “There were kids in the street playing with a soccer ball, and behind them was a poster of energetic children running around, so I combined those.” That marked his first use of an image within an image, which would become a recurring theme in his work.

Like many talented artists, Josephson was fortunate enough to find good mentors. In Rochester he studied with Minor White, an American photographer known for having students stare at a single image for prolonged periods. In Chicago, where he moved in 1958 to pursue a graduate degree at the Illinois Institute of Technology, he was taken under the wing of two greats in the genre: street photographer extraordinaire Harry Callahan and master of abstract images Aaron Siskind. Both men’s sensibilities can be seen in Josephson’s work.

“I learned a lot just from observing those two,” Josephson says. “Harry wouldn’t talk very much, but Siskind was very verbal. Often Harry would say, ‘That’s a good picture,’ but that’s it. And Siskind would add, ‘What Harry means is . . .’ They were a very good team.”

A self-portrait from the 1970s

Josephson began teaching at the Art Institute of Chicago in 1960, a gig that lasted on and off for nearly 40 years. He got a major career boost when the late John Szarkowski, then the director of photography at New York’s Museum of Modern Art, included his work in MoMA’s influential 1964 show “The Photographer’s Eye.”

While suffering his fair share of tragedies — including the death of his first wife, Carol, and his son Matthew — Josephson built his career brick by brick, constantly hunting for poetic compositions of light and dark. He traveled often, including to India, where the took a memorable series of photographs, but always ended back in Chicago.

These days, if you’re in the Loop — Chicago’s famed business district, surrounded by the elevated train — you may still find Josephson with his Leica or Rolliflex in hand, searching for something to frame.

“I like the high contrast of light there and the architecture. Some of the buildings are quite dark, and the train casts a lot of shadows,” Josephson says, adding, in an indication of the close attention he pays to the nuances of his art. “But it’s best with a northwest wind. That way the air is totally clear.”