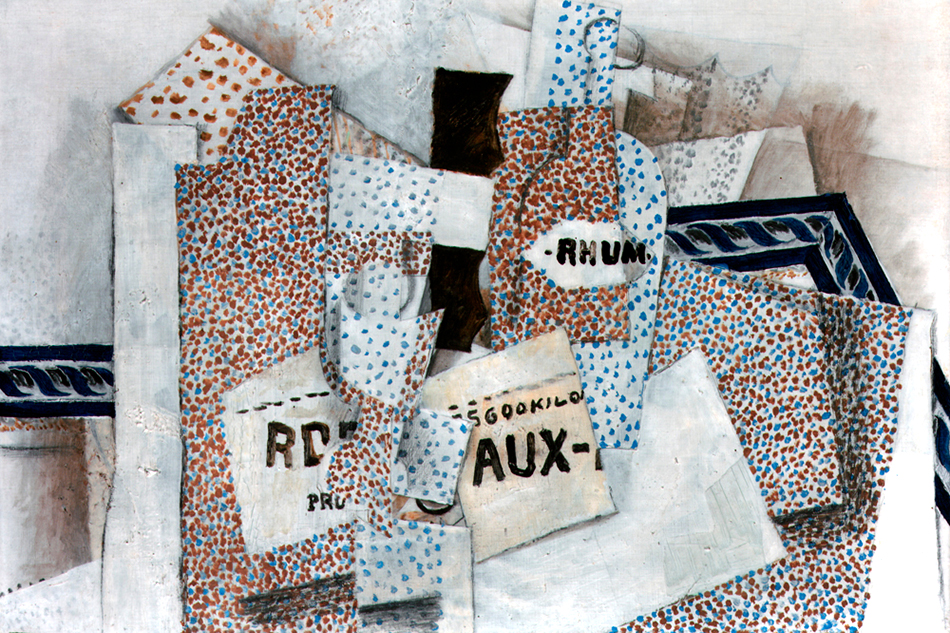

July 17, 2013The recent gift from cosmetics scion, art collector and philanthropist Leonard Lauder, seen above with the author (photo by Julie Skarratt), to New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art of nearly 80 Cubist pieces includes Fernand Léger’s Le typographe (The Typographer), 1917-18 (image © 2013 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris).

In my 40-some years as a magazine editor, I’ve met a good many CEOs of companies, both large and small. Correction: Not all of them were good, and some were downright dreadful. The truth is that only a handful stand out in my mind as true leaders — individuals to inspire and admire. Leonard Lauder is one of them. If his recent donation to New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art of some 78 world-class Cubist paintings, drawings and sculptures isn’t proof enough, then consider his résumé prior to this historic gift.

As the eldest son of Estée Lauder, he took the cosmetics company that his mother and his father Joseph founded in 1946 and turned it into a multibillion-dollar empire that not only spawned Aramis, Clinique, Prescriptives and Crème de la Mer, but he also acquired and grew M.A.C., Bobbi Brown, Jo Malone and Darphin. On his watch, Estée Lauder went public and further expanded through licensing agreements with the fragrance divisions of Tom Ford, Tommy Hilfiger, Donna Karan and others. Having started with the company in 1958, today Lauder is the senior member of its board and has transitioned into the role of chairman emeritus. The new position hasn’t caused him to stop, however — or even to slow down. All he’s done is shift focus to some of his many other areas of interest.

Lauder is hardly just a highly successful businessman; he’s a true Renaissance man. Granted, that’s an overused expression, but, in Lauder’s case, it applies tenfold. Seemingly tireless, he is a connoisseur of the visual arts, a music lover, a world traveler, a major philanthropist, a health advocate, a mentor to many. His days are long, starting early and extending well into the evening. When he gets home, at the time most of us are turning down the covers, Lauder is writing thank-you notes to whomever hosted him that night.

Lauder poses in Palm Beach, in 1979, with his mother, Estée, his wife, Evelyn, and their son, Gary.

For 52 years, until her death in 2011, Lauder was married to Evelyn Lauder (née Hausner), who played a huge part in the family business and established the Breast Cancer Research Foundation, which the Estée Lauder Companies warmly embraced and raised millions of dollars for. Together, they were among the most admired — make that beloved — couples in America. When he lost her, he lost his soulmate and, many thought, the will to go on. But whatever emotional reserves Lauder had on tap kicked in, and now, at the age of 80, he has enthusiastically embraced the latest chapter of his rich, full life.

For a period after Evelyn’s death, Lauder was known around town as the most eligible man of a certain age. But serial dating didn’t appeal to him. (In fact, he is now in a serious relationship and likely to remarry.) On the other hand, collecting art — from postcards to paintings — did appeal, and it still does. Whatever the field, he pursues his quarry with the glee of a boy and the seriousness of a scholar.

His longtime involvement with the Whitney Museum of American Art, in Manhattan, was as chairman, donor and friendly persuader. The last role might have been the most significant: Adam Weinberg, the Whitney’s director since 2003, credits Lauder with bringing him back to the museum where he’d once been a curator. “Leonard had me over to his apartment one Sunday night for cocktails and chopped liver, literally. I was then director of the Addison Gallery of American Art at Phillips Academy, in Andover. Leonard persuaded me that the Whitney directorship would be the chance of a lifetime. As usual, he was right. ”

Just before Weinberg returned, Lauder brought together a group of trustees to donate some of their art to what became known as the American Legacy gift: 87 paintings by Jasper Johns, Ellsworth Kelly, Robert Rauschenberg, Barnett Newman, Roy Lichtenstein, Mark Rothko, Andy Warhol, Claes Oldenburg and Jackson Pollock. To call such a gift magnanimous would be an understatement — and such extreme magnanimity couldn’t have been done without Lauder’s gentle prodding. “He spearheaded the whole thing,” says Weinberg, “by using his own gifts to leverage the gifts of others.”

During Weinberg’s tenure, Lauder gave the Whitney his own in-depth collections of Elie Nadelman, as well as drawings by Brice Marden and Oldenburg. “Beyond Gertrude Whitney herself, Leonard is one of the top two or three patrons of American art,” says Weinberg matter-of-factly.

Pablo Picasso’s Femme assise dans un fauteuil (Eva) (Woman in an Armchair), 1913, is the first of the Lauder gifts to go on view at the Met. Photo © 2013 Estate of Pablo Picasso/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Lauder generally thinks big, but he can also think small — as small as a picture postcard. He started collecting them when he was seven or eight years old, purchasing five postcards of the Empire State Building. The collection eventually became so enormous that he finally had to think about housing it in museums, among them Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts, which recently exhibited 700 of the collection’s 70,000 (you read that right) Japanese examples. Boston MFA curator Ben Weiss has the highest respect for Lauder. “This is a guy who has his head screwed on straight,” says Weiss, “which is not always the case when it comes to collectors.”

His postcards “hail from all over the world and date back to 1869, when the postcard was created in Austria,” Weiss continues. “They were brought together by Leonard himself because he resisted buying other people’s collections. Although it is not the largest — that belongs to the Library of Congress — there is no parallel collection anywhere. These are postcards as art, and you can find therein every societal twitch.”

Lauder’s latest gift goes well beyond a twitch. It’s more like a seismic shift. In early April, the front page of the New York Times was emblazoned with the news that Lauder would be giving his collection of Cubist masterworks to the Metropolitan Museum of Art. To be exact, that would be 33 pieces by Picasso, 17 by Braque, 14 by Léger and 14 by Gris. Their cumulative value: more than $1 billion dollars.

What does this mean for the museum’s existing collection of modern art? In a word, everything. “There were holes in the collection,” admits Rebecca Rabinow, who is the Met’s Leonard A. Lauder Curator of Modern Art. “Some key objects were missing.” Not any more.

“Lauder considers this a gift to the city and to the people of New York,” says Rabinow. “It gives the Met a new way to walk into the twentieth century” — that is to say, with a spring in its step. And here’s the punch line: There are no strings attached (which is also not always the case when it comes to collectors).

In the New York Times story announcing the Met gift, Lauder said: “Whenever I’ve given something to a museum, I’ve wanted it to be transformative.” Photo © Roberto Portillo, courtesy MFA, Boston.

What does come as part of the gift, however — a bonus, if you will — is a research center in Lauder’s name. Devoted to Cubism and early modern art, it will allow scholars to carry on intensive study. For Sheena Wagstaff, who joined the Met in 2012 (she’d previously been chief curator of the Tate Modern, in London), the prospect of the center is nearly as thrilling as the collection itself “because it allows for genuine scholarship.”

Lauder began collecting Cubism in the mid-1970s when, as he told the Times in April, “nobody really wanted it.” Call him a visionary or one clever fellow, but the fact is Lauder took an interest in Cubism for no other reason than that it appealed to his aesthetic.

Wagstaff, whose title is Leonard A. Lauder Chairman of Modern and Contemporary Art, has nothing but praise for Lauder’s vision: “He went against the grain by collecting Cubism, and for that I admire him tremendously. Cubism is an intellectual pursuit, which includes a great deal of texture and eroticism, both depicted and implied.”

As for working with Lauder, Wagstaff compares him to an “intellectual chess player who’s always a couple of steps ahead of you. He likes to test and tease, always pushing for clarification. And he doesn’t mind being pushed back.”

As of this writing, only one of the paintings — Picasso’s Woman in an Armchair, a 1913 portrait of his mistress Eva Gouel — is on display at the Met, in the museum’s first-floor galleries. But in 2014, museum-goers can expect a special show featuring all the works together.

Talk about a legacy.