May 11, 2015French landscape artist Louis Benech imagined his new design of the Bosquet du Théâtre d’Eau at the Château de Versailles as a joyous promenade around a water theater and its surrounding greenery. Top: Benech’s revamped bosquet spotlights the gilded Murano glass fountain sculptures by sculptor Jean-Michel Othoniel. All photos by Francis Amiand unless otherwise noted

Louis Benech is France’s most renowned landscape artist. Already known internationally, he will step even more firmly into the spotlight when his revamp of the 17th-century Bosquet du Théâtre d’Eau (Water-Theater Grove) at Versailles opens to the public on May 12. Benech’s project will be the first-ever contemporary redesign within the historic gardens, which were conceived in the 17th century by Louis XIV’s legendary landscaper André Le Nôtre.

Charming and disarming, with a salt-and-pepper beard that lends his classic leading-man looks a more countrified allure, Benech, at 58, has steadily risen to occupy as prominent a place in contemporary French landscaping as Jacques Grange does in interior decoration. During his 30-year career, Benech has created more than 300 gardens that span the globe. Among them: the Tuileries, in Paris (his restoration, in 1990, with Pascal Cribier, established his reputation); Pavlovsk’s Rose Pavilion, in St. Petersburg, Russia; Château Mouton Rothschild, in Bordeaux; and the presidential Elysée Palace, in Paris.

An exceptional plantsman, Benech is admired for his fresh, environmentally sensitive designs that are at once formal and informal and full of impressionistic color. The gardener is also noted for his ultra-discretion. But when your list of clients includes such starry names as François Pinault; Monaco’s Caroline, Princess of Hanover; banking heir Loel Guinness; Guy and Marie-Hélène de Rothschild; Jacques Grange; gallerist Pierre Passebon; and Benech’s longtime partner, shoe guru Christian Louboutin, word slips out.

Benech has been awarded the French Legion of Honor; he’s a Chevalier des Arts et Lettres and a member of the British Royal Horticultural Society — so everyone must have assumed he was a shoo-in when the Chateau de Versailles announced an international competition for a contemporary redesign of this bosquet. (Over the centuries, the grove had been neglected, and then damaged beyond restoration by a pair of ferocious storms in the 1990s.) Everyone, that is, except the refreshingly modest Benech. “My drawing of the design was hideous,” he confesses, “and I was terrified by the competition.” Benech’s drawings “are practical, not artistic,” he explains — but a beautiful presentation does not always result in a beautiful garden.

Benech asked Othoniel to re-imagine the bosquet’s fountains after he saw children paying rapt attention to the sculptor’s work at an exhibition at the Pompidou in 2011. The garden’s 17th-century theme was “Childhood;” its 21st-century reincarnation is for everyone.

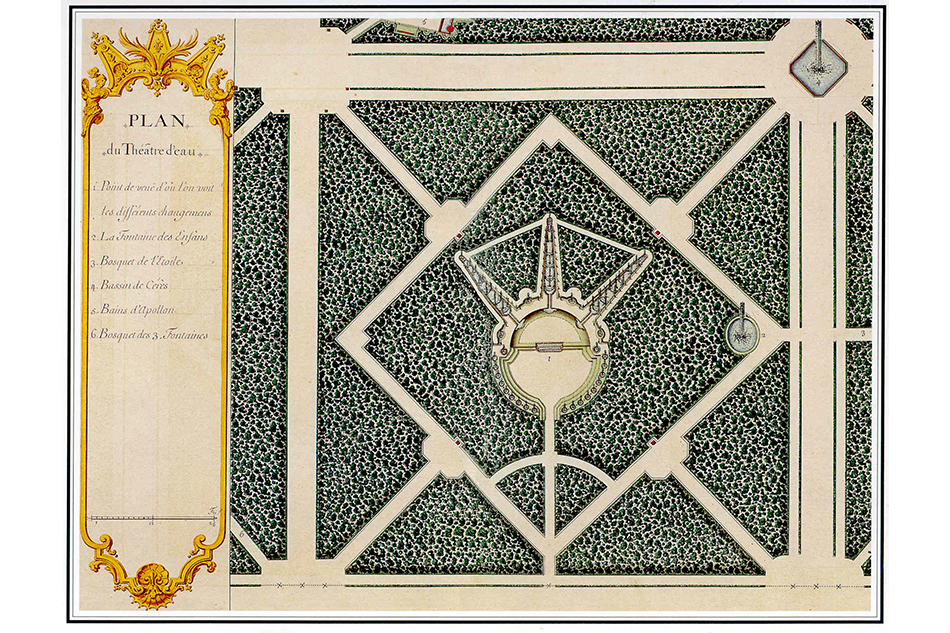

Benech’s vision for this nearly four-acre grove combines nature, water and theater with an elegant nonchalance. Among Versailles’s most elaborate bosquets, the original Water Theatre, constructed by Le Nôtre between 1671 and 1674, has long been considered one of the 17th-century landscape architect’s most ingenious designs. Inspired by Palladio’s Olympic Theater in Vicenza, Italy, he invented three allées of waterfalls that converged on a dreamlike circular amphitheater and stage. Devised to surprise, complex topiaries concealed other watery spectacles from visitors until they were fast upon them. Statuary was overseen by Charles Le Brun, first painter to the king, who was later made a nobleman.

For his re-imagining, Benech linked up with contemporary sculptor Jean-Michel Othoniel, and, despite Benech’s worrisome sketch, his design won the commission in 2012. “I decided to rely on very simple facts — to make a water theater and to do it in a similar way to how Le Nôtre worked: not alone, but with a team of artists,” Benech explains. He notes that his plan features a series of graceful ovals containing a waterway of connecting pools — three of them ablaze with Othoniel’s dramatic sculptures — and an amphitheater surrounded by trees.

The bosquet‘s original theme, childhood, was imposed on Le Nôtre by King Louis XIV himself. “He loved children and had many of his own, but he he never really knew a normal childhood himself,” Benech explains. (Crowned before his fifth birthday and terrified, at the age of 10, by the Fronde revolt, it’s no wonder that the Sun King decided to remove himself to Versailles, away from unruly Parisian mobs.)

Other Gardens by Benech

“I decided to rely on very simple facts — and to do it in a similar way to how Le Nôtre worked: not alone, but with a team of artists.”

Othoniel’s swooping arabesques of gold leaf–lined Murano glass were inspired by an 18th-century book filled with symbols for baroque dance steps. Four large blue glass boules mark the locations of the bouquet’s original fountains, which featured sculptures of cavorting children.

“I wanted to hold onto the bosquet’s original conception of childhood,” Benech adds, “when all of the fountains had sculptures of children playing.” For his new version, he thought of Othoniel, who is celebrated for his dynamic, multihued glass-bead sculptures — and in particular one work that decorates the Métro entrance in the Place du Palais Royal. When Benech went to see the Pompidou’s 2011 exhibition of Othoniel’s work, he noticed how fascinated children were with the artist’s joyful sculptures — so he asked him to join the project.

The Paris-based 51-year-old Othoniel brought his own ingenuity to the design after discovering, in a Boston library, L’Art de Décrire la Danse — a 1701 book by the choreographer Raoul-Auger Feuillet that included his graphic symbols for royal dance steps. The swirling calligraphy of baroque minuets and rigaudons danced by the king and his courtiers became Othoniel’s inspiration for the swooping arabesques of gold-leaf–lined Murano glass boules in “Les Belles Danses,” his three Théâtre d’Eau fountains. These sculptures represent a trio of dances: L’Entrée d’Apollon, Le Rigaudon de la Paix and La Bourée d’Achille, all posed upon Benech’s pools, which serve as the “stage.”

Four large blue-glass boules mark the positions where there were groups of children playing in the original fountains. Le Nôtre favored circles, but for the major outlines of his plan, Benech adopted the oval shape of the nearby Fontaine des Enfants Dorés — designed as L’Île des Enfants in 1710 — which is still under restoration. Like the king’s landscaper, Benech also inserted different geometries inside the larger organizational forms. He re-introduced Le Nôtre’s deployment of multiples of three, from the 18 jets of the colonnade to the 90 live oaks that assure a year-round evergreen presence. “The number three doesn’t come out of the blue,” Benech asserts. “It represents the Holy Trinity. Louis XIV liked to remind his courtiers that his power didn’t come from them, but by divine right from God.”

A life-long lover of trees and plants, Benech gained international renown in the early 1990s as part of the team that revamped Paris’s Jardin des Tuileries during the Grand Louvre project; since then, he has gone on to complete even bigger commissions around the world. Photo © Château de Versailles, Thomas Garnier

During a preview visit in mid-April, Benech himself explained his favorite element: a little island with two trees: an untrimmed boxwood and a lopsided Irish yew. Both are possible descendants of Le Nôtre’s plantings, and both are survivors of those two terrible storms — “without which I wouldn’t be working here,” Benech said.

We walked along the promenade that encircles the pools and provides different Water Theater perspectives; sometimes only the spray of the jets is visible, while at other points, one has close-ups of the peninsula and island. (The views will evolve, of course, as the garden matures.) Benech’s custom “Versailles XXI” benches, made of light-gray, ultra high-performance concrete with fluted, red marble legs, offer spots for rest and repose along the way.

Le Nôtre notoriously hated flowers, so the surprise is that Benech has included what he describes as “tons” of blooms, including pink beauty bush, honeysuckle, snowballs, hellebores, irises and some sweet box — and carpets of some 60,000 tiny pale-violet periwinkles that are already peeping out from their leaves. The landscaper intends to respect Le Nôtre’s edict of limiting tree height to 56 feet; today the maples, beeches and live oaks he planted are still young saplings. “When you come into the garden now, you see right through the trees,” he explains, “but in a few years, the walk will be a tunnel of shade made by a green canopy.”

When the king visited the grove, fountains splashed for his arrival and were turned off after he passed. (The innovative waterworks were then under the direction of hydraulic engineer François Francine.) Benech’s grove is designed to withstand the attentions of Versailles’ six-million annual visitors; it will be the only bosquet open in all seasons, every day.

On the day of my visit, rain had been forecast, but the morning sun shimmered over the bouquet’s pools and their golden glass sculptures. The fountains were turned on in a dazzle of whirling spray, and it seemed as if the Sun King himself was dancing across the water’s effervescent surface.