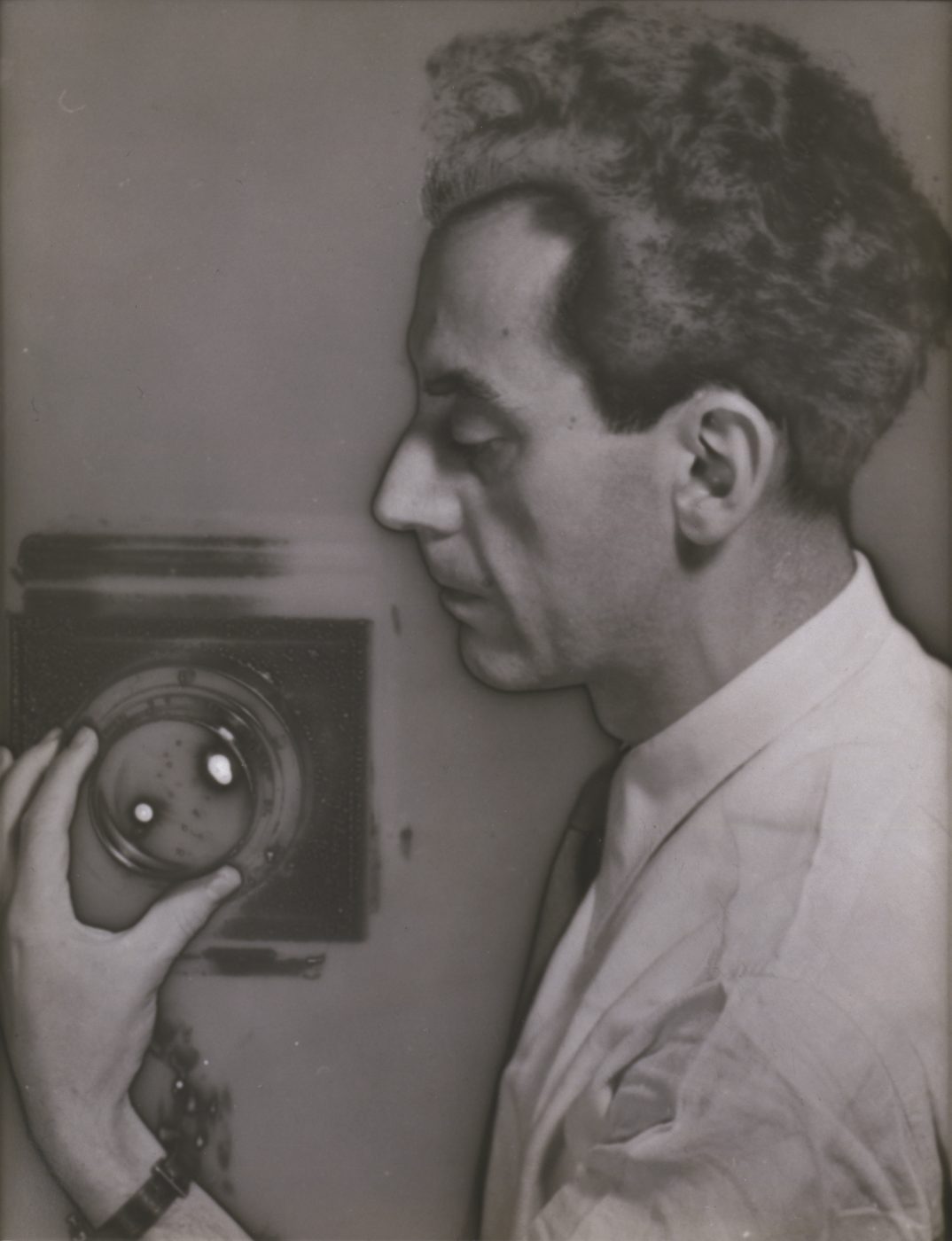

January 23, 2022A century before it became commonplace for contemporary artists to work across disciplines, Man Ray (1890–1976) pioneered a multimedia studio practice in painting, sculpture, collage, filmmaking, assemblage and printmaking. Yet he may be best remembered for his work as a photographer, including his own RAYOGRAPH darkroom technique.

“You really can’t tell the history of photography without Man Ray,” says Michael Taylor, chief curator and deputy director for art and education at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, where he has organized “Man Ray: The Paris Years,” on view through February 21.

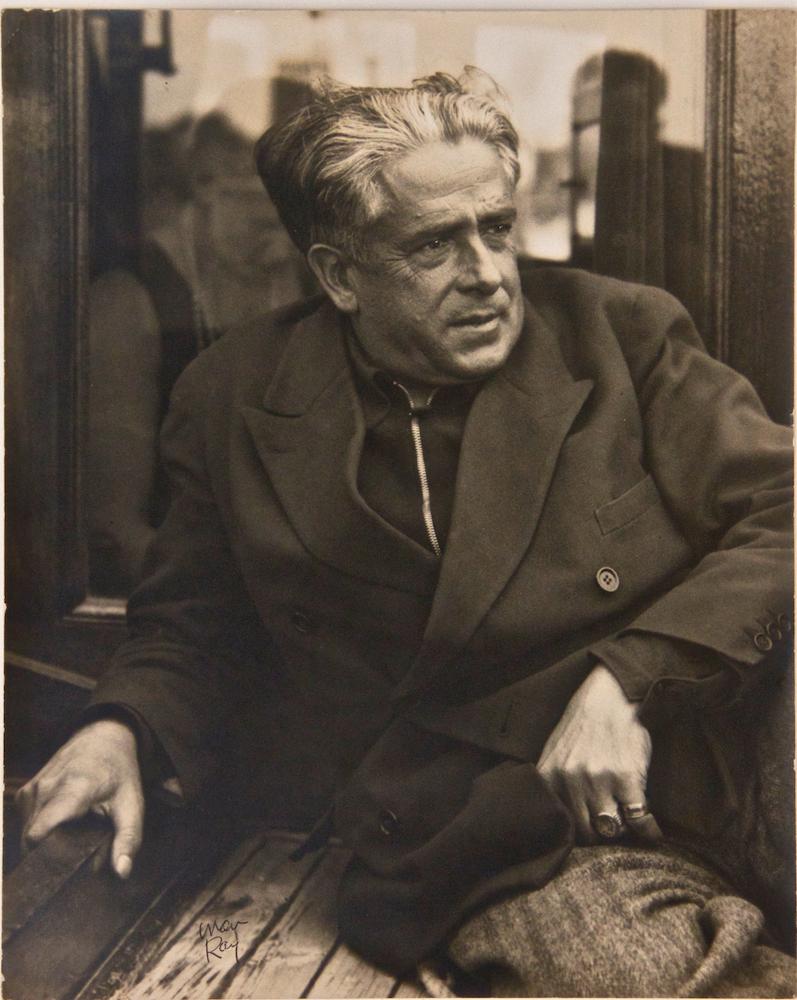

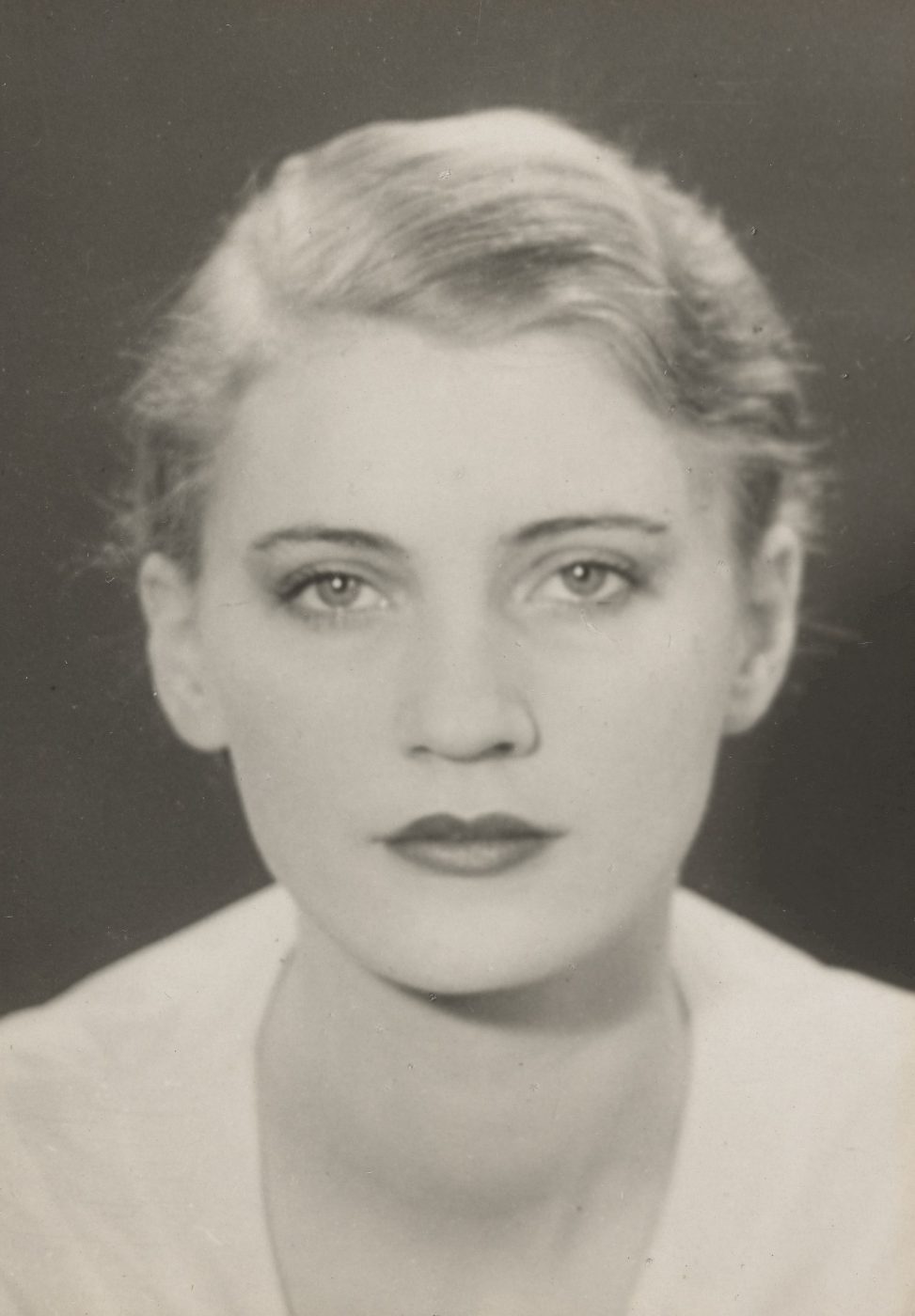

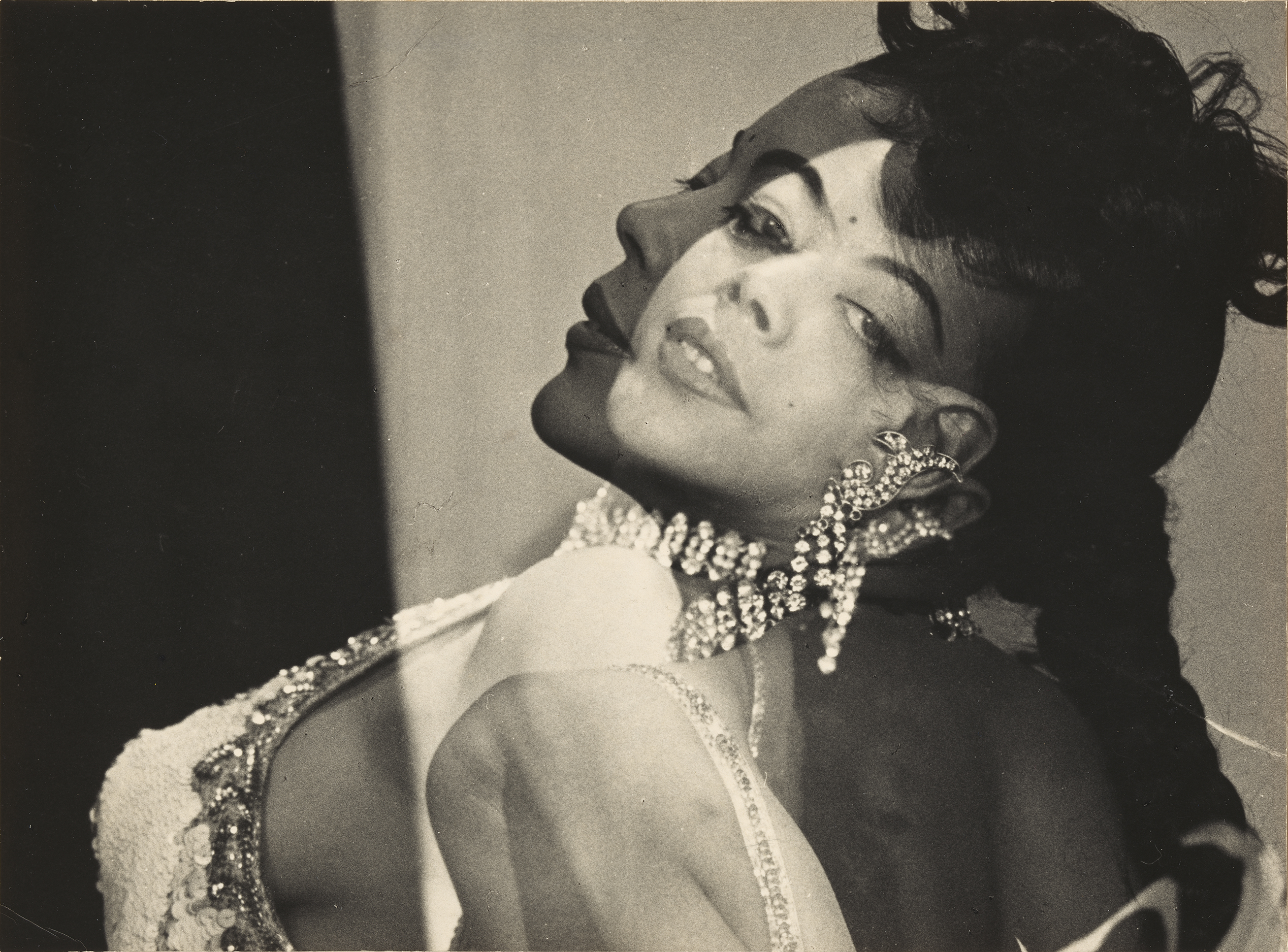

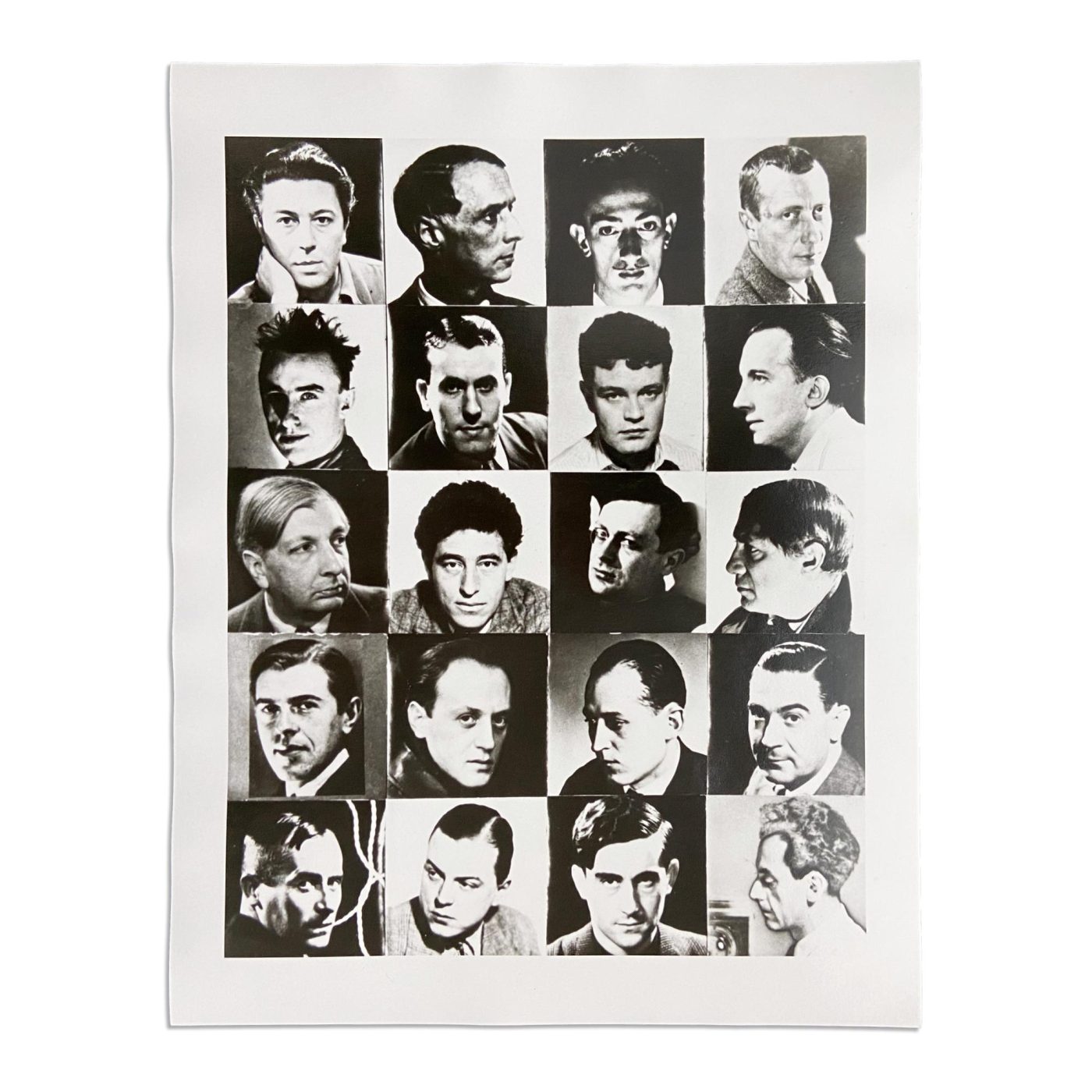

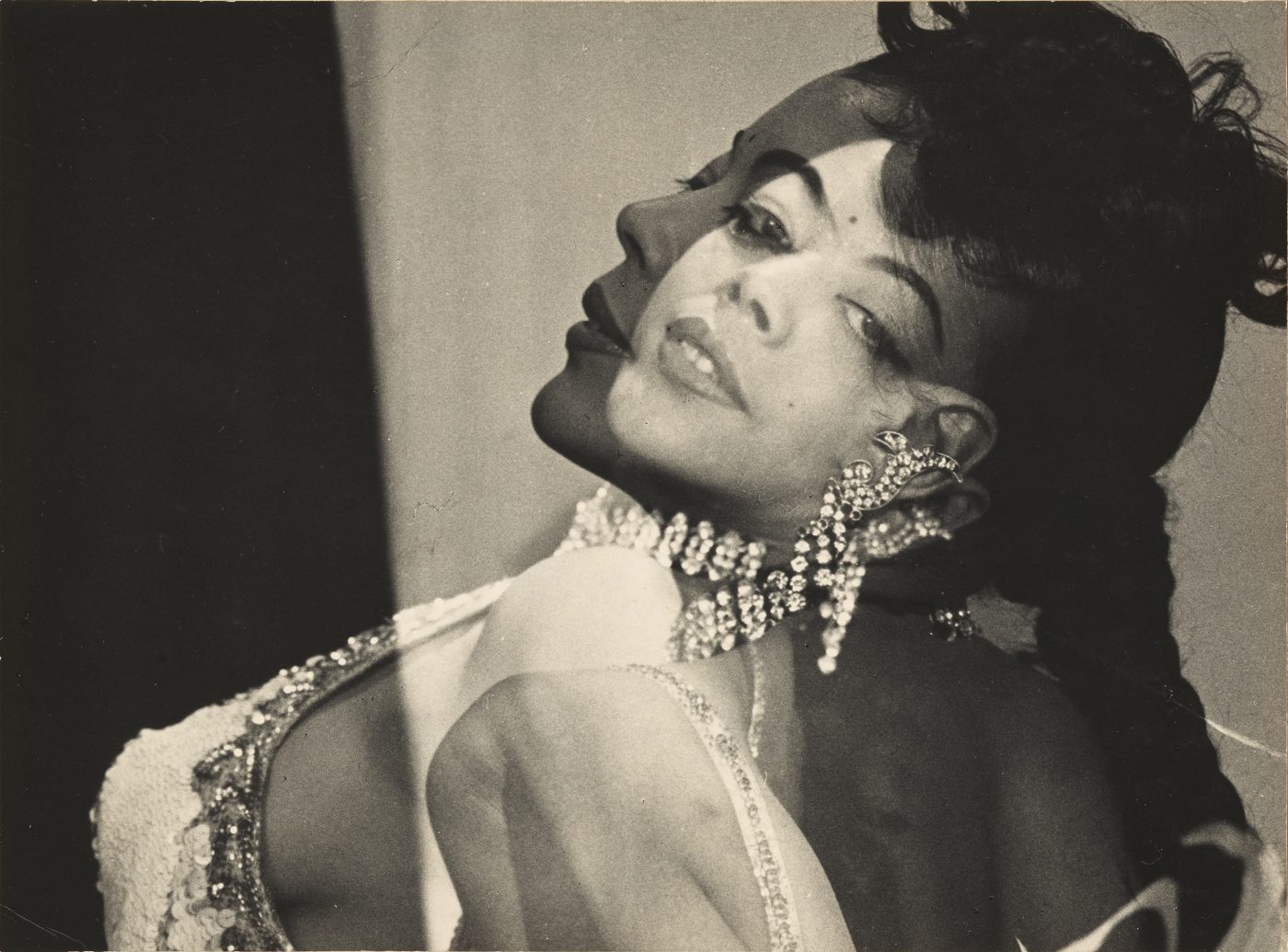

Among Man Ray’s portraits of interwar creatives in the show “Man Ray: The Paris Years,” at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, are Self-Portrait with Camera, 1930 (above); and (top, from left) Elsie Houston, 1933; Berenice Abbott, 1921; and Kiki de Montparnasse, ca. 1924. © Man Ray 2015 Trust/Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY/ADAGP, Paris 2021

The show focuses on Man Ray’s groundbreaking work in portraiture, including more than 100 photographs shot between the World Wars, from 1921 to 1940, when Paris was a mecca for artists and performers of all types.

“You have all these people like Gertrude Stein and Jean Cocteau and James Joyce living in the same city, and Man Ray is the one photographing them,” says Taylor.

Born to Russian immigrant parents and raised in Brooklyn, Emmanuel Radnitzky started out as a painter in the mode of the Ashcan school, adopting the pseudonym Man Ray around 1912. After seeing the 1913 Armory Show, which exhibited Marcel Duchamp’s revolutionary painting Nude Descending a Staircase (No. 2), Man Ray embraced Cubism and Dada.

He taught himself photography initially as a means to document his artwork. The sale of some of his paintings to the collector Ferdinand Howald funded Man Ray’s trip to Paris in July 1921. By November, he was supporting himself with photographic portrait commissions, writing to Howald that the pursuit “helped me meet all the interesting French people here.”

Left: Gertrude Stein (at Home), 1922. Right: Barbette, 1926. © Man Ray 2015 Trust/Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY/ADAGP, Paris 2021

One commission quickly led to another, and certain patrons became key connectors. Through Francis Picabia, Man Ray met Cocteau, who sat for several portraits; promoted the artist’s work on the walls of Le Boeuf sur le toit, a jazz club he haunted; and sent a stream of customers to Man Ray’s door.

So did Gertrude Stein, who used Man Ray’s portraits of her and Alice B. Toklas to help publicize their famed salons in publications like Vanity Fair. (Stein refused to pay Man Ray an outstanding bill for 500 francs in 1930, writing, “We are all hard up, but don’t be silly about it,” and they never spoke again.)

Man Ray became the Surrealists’ “official” photographer through his friendship with the movement’s leader, Andre Breton, publishing frequently in the 1930s Surrealism-favoring magazine Minotaure. (Breton described Man Ray as having “the eye of a great hunter.”) The influential bookstore owner Sylvia Beach sent writers in need of publicity photos to Man Ray. He caught James Joyce resting his eyes between takes and embraced that accidental image for its melancholic affect.

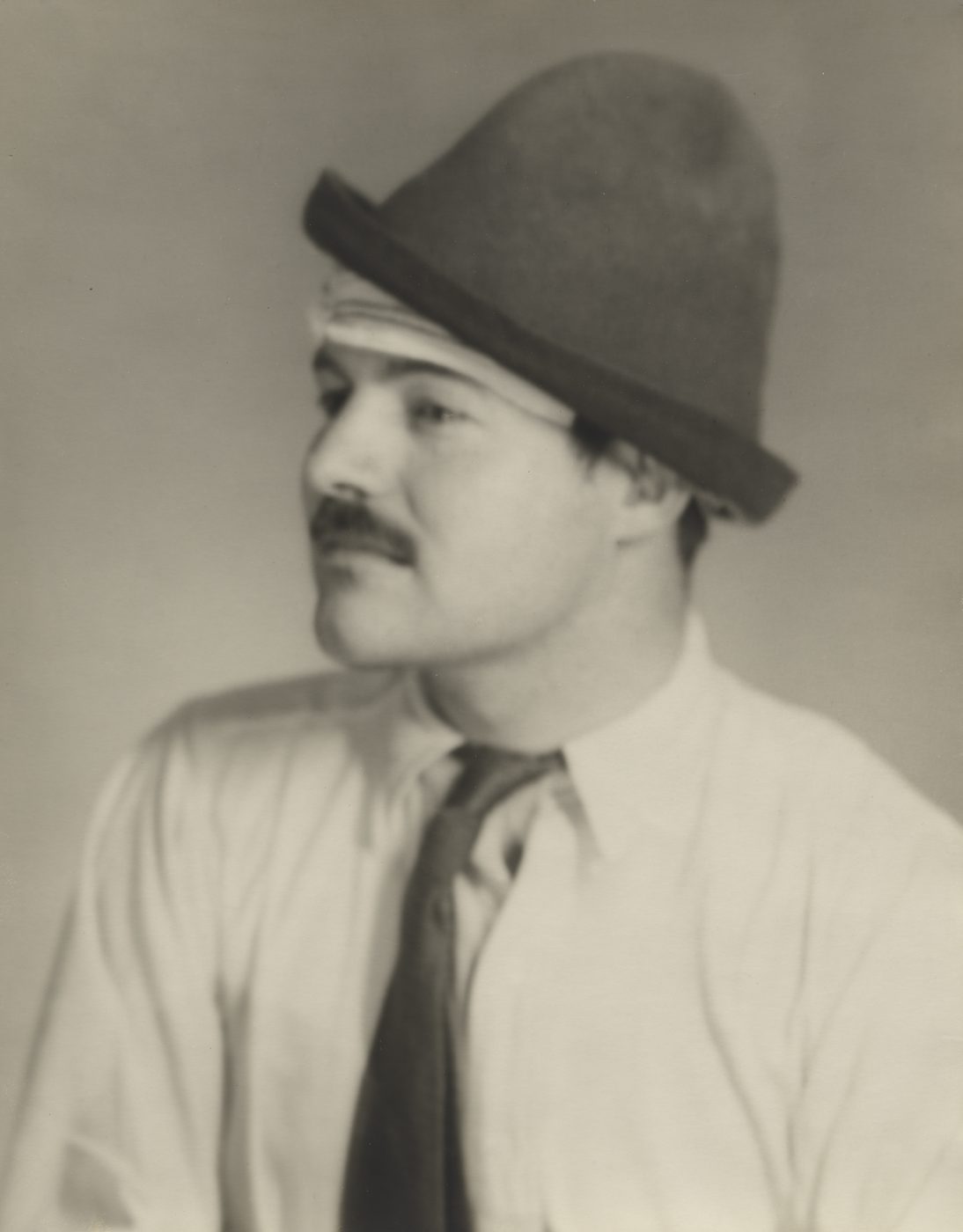

Ernest Hemingway, 1928. © Man Ray 2015 Trust/Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY/ADAGP, Paris 2021

The who’s who of creators passing through his studio — Ernest Hemingway, Igor Stravinsky, Elsa Schiaparelli and Le Corbusier, among many others — places Man Ray in the lineage of Nadar in the 19th century, and Annie Leibovitz today, each creating a pantheon of images of the cultural personalities of their particular eras.

Although Man Ray may have started the commissions as a way of making a living, “I don’t think he saw a distinction between his regular practice and his portraiture,” says Taylor, who in 2017 steered the acquisition of 50 major portraits from Timothy Baum, the artist’s exclusive dealer in the 1970s and his estate executor. As a result, the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts has one of the world’s great Man Ray collections, which provides the backbone of the show.

Man Ray was certainly opportunistic in the heyday of photo-magazines, getting paid twice, for instance, for his portrait of Virginia Woolf: once when he took it, in 1934, and again three years later, when Time used it on the cover.

He turned away society people he didn’t like and hounded other potential subjects for a sitting, like sculptor Constantin Brancusi, who stares down the viewer with light raking across his massive beard and cardigan. (The Brancusi portrait in the “Paris Years” is one of three prints on loan to the exhibition from the collection of Elton John.)

Compared with standard studio portraiture of the time, which relied on props and decorative backdrops, Man Ray’s technique was radical: He isolated sitters against a burlap background and used strong lighting inspired by the painted portraits of Rembrandt and Holbein. “His studio is like a laboratory, and he’s honing in on these psychologically charged images, just you and the camera,” says Taylor.

Man Ray maintained that the “secret of good proportions” was shooting people from a distance of no less than four meters (around 13 feet), then cropping, enlarging and sometimes reorienting the final print. In the portrait of Georges Braque, for instance, the artist’s head and gaze have been re-angled upward for a more confident look.

Braque — like Max Ernst and Meret Oppenheim, among other sitters — also got the photographer’s solarization treatment, which edges the outline of his subjects with a dark glowing halo and amps up their wattage. The technique was the accidental invention of Lee Miller, Man Ray’s studio assistant and lover from 1929 to 1932, who re-exposed a negative to light during development when a mouse ran over her foot. Man Ray perfected and exploited the effect.

In 1940, as the Germans were advancing on Paris, Man Ray retreated to the U.S., settling in Los Angeles for the next decade and returning to painting as well as filmmaking. (The Hollywood studios were not particularly receptive to his avant-garde work.) In 1951, he headed back to Paris, where he stayed for the remainder of his life. He continued to make portraits as part of his studio practice, but the City of Lights had lost out to New York as the capital of the arts, where everyone had to be.

Man Ray was one of the first artists to have a solo museum exhibition of just photographs, at Connecticut’s Wadsworth Atheneum, in 1934, featuring pictures from what Taylor sees as Man Ray’s most prolific and experimental period, from 1921 to 1940 in Paris. “I do think his greatest work was done then,” Taylor says. “For Man Ray, it was a golden age.”