June 26, 2017Contemporary artist Mark Ryden has created a sugary fantasy world for a new ballet by choreographer and American Ballet Theatre artist-in-residence Alexei Ratmansky. Performed this week at New York City’s Metropolitan Opera House, the production features sets and costumes that are as sweetly seductive as they are alarming. Manhattan’s Paul Kasmin Gallery and the opera house’s Gallery Met is currently displaying sketches, paintings and drawings of Ryden’s designs. All photos courtesy Mark Ryden and Paul Kasmin Gallery unless otherwise noted

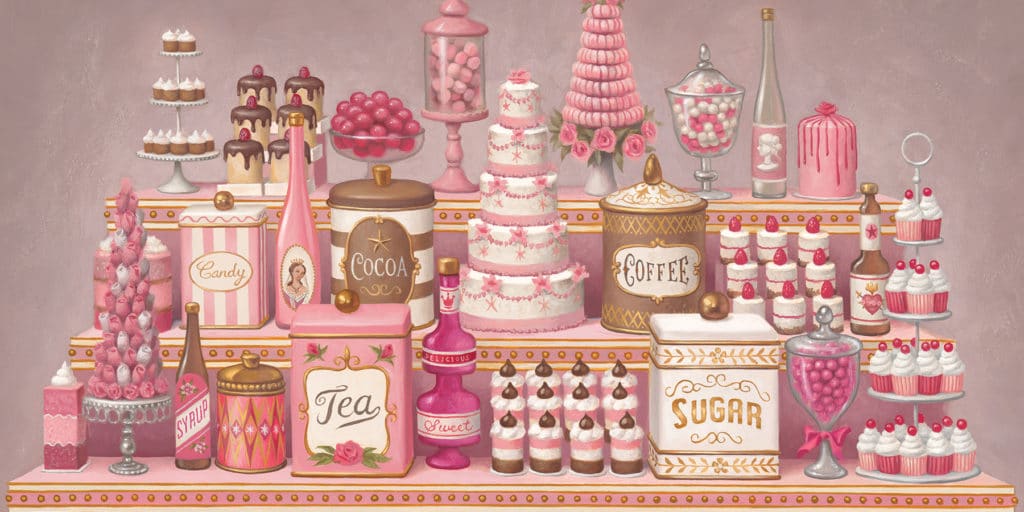

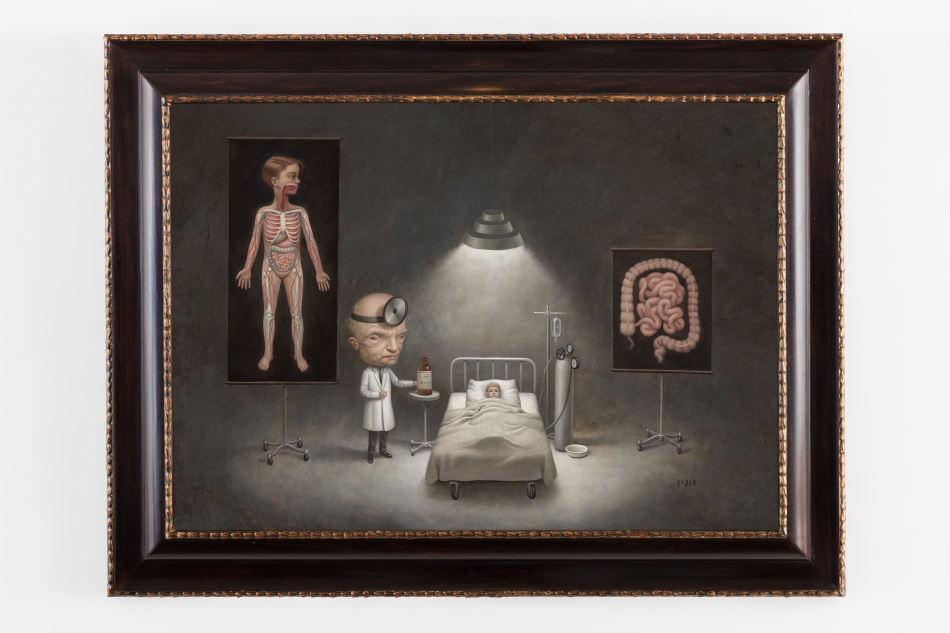

Pillowy clouds of whipped cream several stories high, a girl in a huge skirt made of gum balls, a man with a head of chocolate, a nurse with a gigantic syringe, the lined and creviced face of a white-coated doctor whose head is 10 times the size of his body — these are some of the fantastical, meticulously imagined sets and costumes created by the Portland, Oregon-based artist Mark Ryden for choreographer Alexei Ratmansky’s ballet Whipped Cream, performed in New York through the end of this week by by American Ballet Theatre at Lincoln Center’s Metropolitan Opera House.

The images — which, in signature Ryden style, teeter vertiginously between the hyper-cute and the grotesque — benefit from close-up viewing. Happily, a show of drawings, paintings and sketches that Ryden created for the production is being hosted by Paul Kasmin Gallery, which represents him, at its West 27th Street space and at Gallery Met, in the opera house.

“We’ve known from the beginning that these designs would be a wonderful exhibition,” says Nick Olney, a senior director at Paul Kasmin. “As soon as we knew Mark would do the ballet, we thought what a great opportunity to show some of the process, as well as more fully rendered images. So there are sketches showing him working toward costume and set designs, as well as detailed drawings and even more fully rendered oils on board.” (Ryden finished these after the ballet opened, to rave reviews, in Costa Mesa, California, in March.)

Ryden, a highly in-demand artist whose work is often described as Pop Surrealism or Lowbrow art, had never previously worked on a theatrical production. “It began with an email, as most things do,” he recounts. “It was from Benjamin Millepied, the director of the Paris Opera Ballet at the time, who was contacting me on behalf of Alexei, who had picked up a book on my work in Japan and wanted to work with me.”

The costume for the ballet’s Princess Tea Flower character features a dress meant to recall flowering-tea leaves.

Several months later, the two men met at a Paris flea market. There, Ratmansky explained that Whipped Cream — called Schlagobers when the ballet had its premiere in Vienna, in 1924 — was set to an almost-forgotten score by Richard Strauss. Its fantastical plot, Ryden learned, involved a small boy who overindulges in sweets and ends up in the hospital in a delirium in which his confections come to life.

“The project seemed really perfect for me,” Ryden says with a laugh. “Alexei seemed to have a similar attitude about art and the sensibility of the piece. He didn’t ask for anything specific, but he wanted something of a disturbing undertone, which is what happens in my work. On the surface, there are these warm, fuzzy images, but there is something deeper and more powerful underneath.”

When the project didn’t come to fruition in Paris, Ratmansky approached Kevin McKenzie, the director of American Ballet Theatre, where the choreographer has been artist-in-residence since 2009. Although it was an expensive proposition, McKenzie was determined to make it work. “I thought the ingredients we had — Mark Ryden, Alexei Ratmansky, Richard Strauss — were so good that we had to go ahead. We threw the whole staff at it,” he says.

Before coming up with any images, Ryden bought and repeatedly listened to a CD of the music. “It had a little booklet with a pretty in-depth synopsis of the ballet that was quite convoluted and comical,” he says. “I bought books on Strauss and read as much as I could, trying to put together some ideas of who the characters were. The original ballet failed because it was so over-the-top, with a lot of political overtones. We went more with the themes of imagination, a dreamworld.”

“He wanted something of a disturbing undertone, which is what happens in my work,” says artist Mark Ryden, describing choreographer Alexei Ratmansky’s vision for the sets and costumes for his ballet Whipped Cream. “On the surface, there are these warm, fuzzy images, but there is something deeper and more powerful underneath.”

“As soon as we knew Mark would do the ballet, we thought what a great opportunity to show some of the process, as well as more fully rendered images,” says Nick Olney, a senior director at Paul Kasmin, speaking about the exhibitions. “So there are sketches showing him working toward costume and set designs, as well as detailed drawings and even more fully rendered oils on board.” Photo by Diego Flores

Creating elaborate dreamworlds is what Ryden is best known for. His meticulously rendered images feature huge-eyed, large-headed waifs who might be wearing dresses made of slabs of meat, praying to “Saint Barbie” or standing warily amid animals (bunnies feature frequently, as do snakes and bears) and religious icons. For Whipped Cream, the artist created exquisite, highly detailed costumes, including one, for Princess Tea Flower, consisting of pink and green flowering-tea leaves; and others, for dancers representing plum brandy, Champagne and vodka bottles, featuring bottle-cap headdresses and large labels.

Ryden didn’t research the designs used for the original production. Instead, he tried to incorporate what he calls “a historical feeling in a very general way, to bring in the nineteen-twenties aesthetic of a Viennese dessert shop.” He adds, however, that this aesthetic “was a reference from which to take off. The surreal elements have more power when you contrast them against a classical starting point. One of the things I really like about the whole production is the contrast between sweet and disturbing.” He thinks for a moment. “Maybe even frightening.”

Visit Paul Kasmin Gallery on 1stdibs