June 26, 2022The Red Studio, Henri Matisse’s bold, monochromatic depiction of a freestanding workspace he constructed at his new home in Issy-les-Moulineaux, is on view this summer at New York’s Museum of Modern Art.

Painted in 1911, this perennial favorite, which entered MoMA’s permanent collection almost 75 years ago, has been reunited with six canvases, three sculptures and a ceramic plate the then-41-year-old French artist portrayed in his luminescent view of his suburban atelier.

The scene looks as if the artist had just stepped out of the room, which is furnished with an easel, an object-laden table, a bureau supporting more stuff, a comfortable chair and a grandfather clock without hands, as well as several pastel sticks and paint brushes.

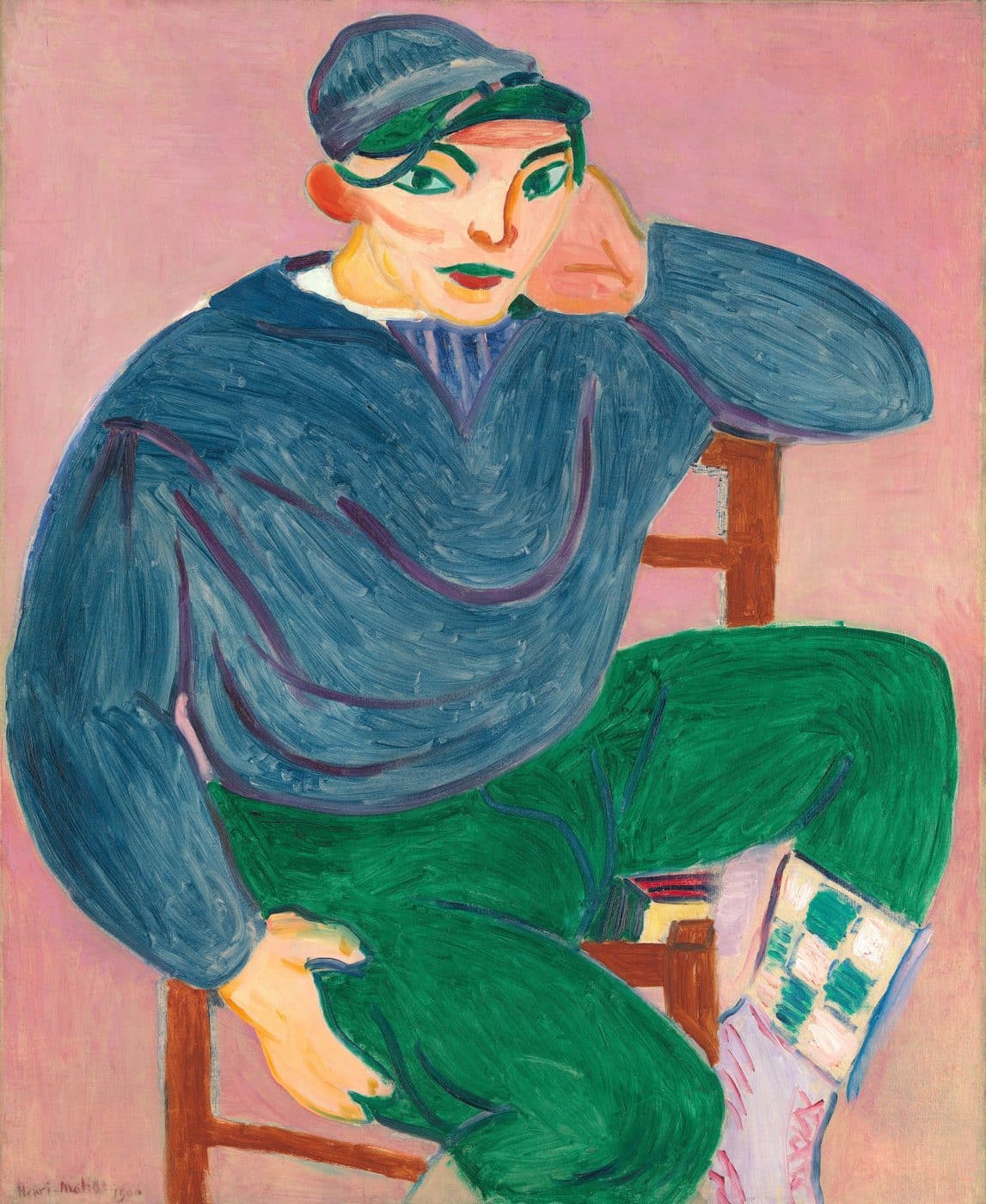

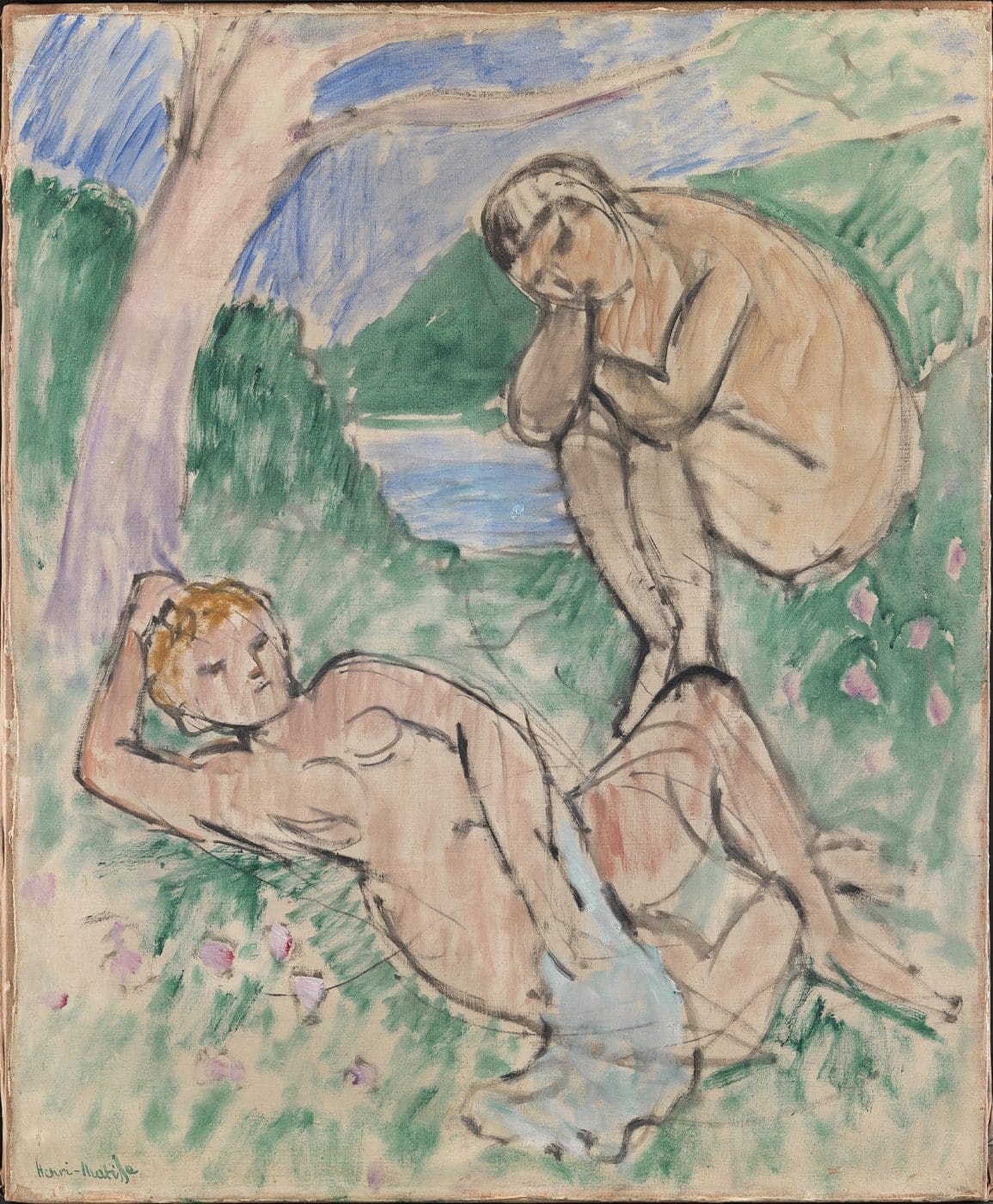

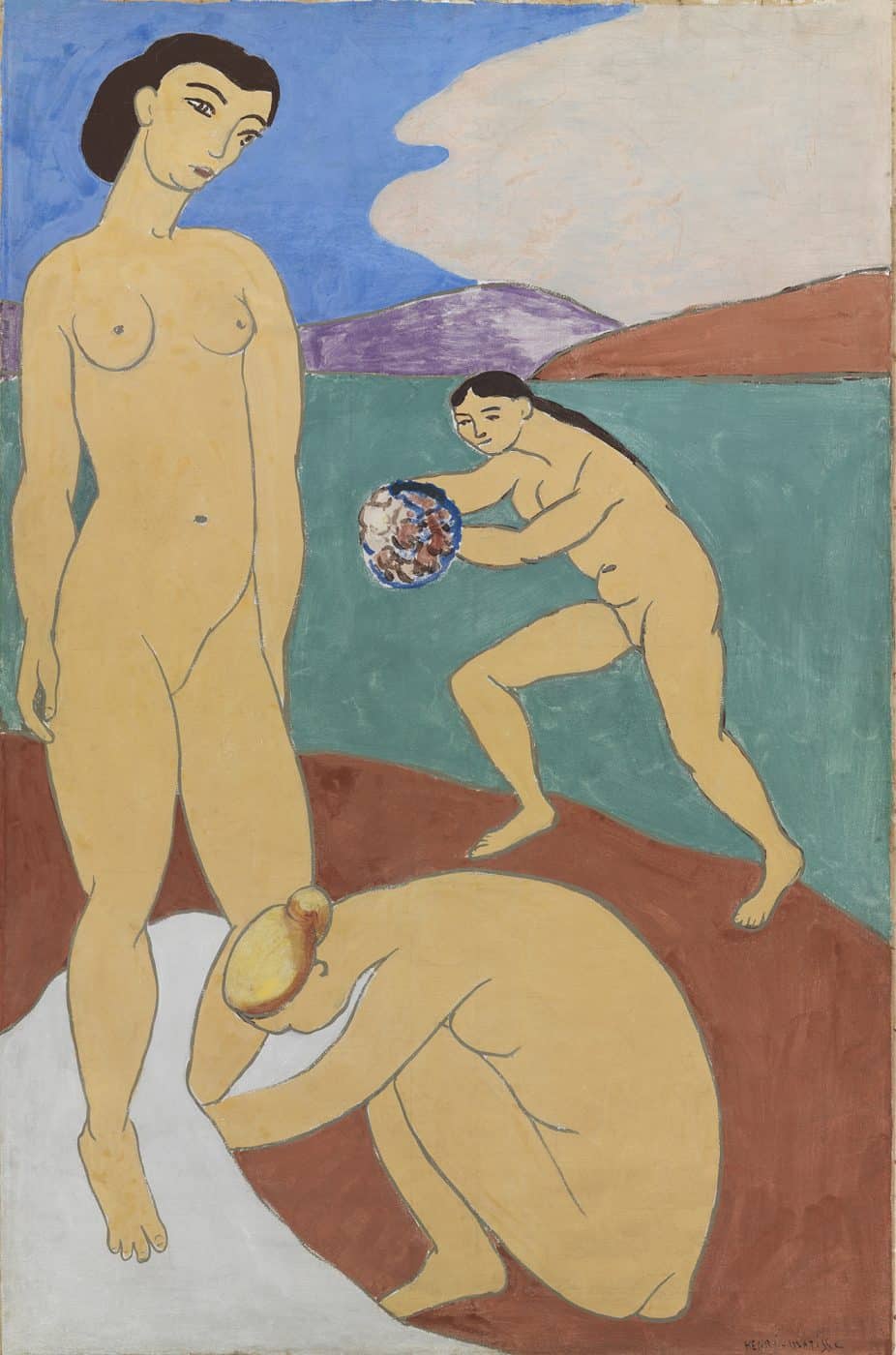

Matisse “depicted what he saw as if he were a camera,” says MoMA’s Ann Temkin, cocurator of the current show. This enchanting time capsule doubles as a visual diary entry for the artist. Shown are landscapes, nudes and a sailor he painted several times — during his honeymoon on Corsica, on vacations to Collioure and in a space he rented in Paris at the former Couvent du Sacré-Coeur. There are also three sculptures Matisse executed in different materials: bronze, plaster and terracotta.

The Red Studio has a checkered history. It was commissioned by the wealthy Russian collector Sergei Shchukin, who already owned 20 works by Matisse. Shchukin wanted three more paintings, all featuring the color blue, to display in his Moscow mansion.

Matisse initially executed the studio view with its walls the requested blue, but at least a month later — when the oil paints had dried, according to MoMA conservators — he covered the surface of the canvas with Venetian red, for reasons unknown today.

A few months later, the Fauvist master admitted to a Hungarian journalist that the rendering of his atelier “has not turned out the way I originally imagined. I like it but I don’t quite understand it.” Shchukin also had reservations. In the end, he declined to purchase the work, explaining that he now preferred paintings with figures. (To be fair, he ended up owning Matisse’s Dance, Music and The Conversation, three riveting figurative masterpieces.)

No one seemed to want to buy The Red Studio. It crossed the English Channel in 1912, when critic and curator Roger Fry featured it in the landmark “Second Post-Impressionist Exhibition” he curated at London’s Grafton Galleries. The painting traveled to New York and Chicago in 1913 and was exhibited in the legendary Armory Show. Following those excursions, Matisse’s red interior languished in his studio. Then, in 1927, an English impresario purchased it for display in the posh private Gargoyle Club.

During the 1940s, The Red Studio bounced from gallery to gallery. It was bought by Georges Frédéric Keller, a Swiss-born dealer living and working in New York, and appeared in a Matisse survey and the Philadelphia Museum of Art in 1948.

MoMA expressed interest in The Red Studio several times in the latter half of the 1940s, finally announcing its acquisition in April 1949. Oddly, although the work has belonged to the museum for seven decades, the concept that connects the paintings Matisse pictured in his atelier was long overlooked: They are all mulligans.

Each is a revision of a completed real-life work. The nude on the left wall, just to the side of a curtained window, is a vertical version of a horizontal picture with which the artist was always dissatisfied. Years after he died, his son Jean destroyed it per his father’s instructions.

The Red Studio itself has a mate: The Pink Studio (1911), which Shchukin already owned when he commissioned the later work. And some commentators have connected The Red Studio to Harmony in Red (The Red Room) (1908), which also belonged to Shchukin. Besides having the same dimensions, both canvases initially had blue walls that Matisse, in the end, made red.

Mark Rothko, according to his biographer James E. Breslin, “spent hours and hours” staring at The Red Studio after MoMA purchased it. “When you looked at that painting,” Rothko said, “you became that color, you became totally saturated with it.”

Temkin points out that Matisse was also “a passion of Alfred H. Barr Jr.,” MoMA’s founding director. The museum mounted a retrospective of Matisse’s work in 1931, the first solo show it devoted to a European artist. Twenty years later, in his classic tome Matisse: His Art and His Public, Barr described The Red Studio as “one of Matisse’s most daring and original inventions.” See for yourself.