September 6, 2020It’s not often that a noted interior designer happens also to be a passionate photographer. But New York–based decorator Matthew Patrick Smyth — whose signature residential projects reveal a preference for livable elegance and soft colors along with a strong focus on detail — is a talented amateur lensman, never without a camera.

“Matthew is a skilled and sensitive designer — and a spot-on fine photographer,” observes legendary aesthetic arbiter Marian McEvoy. “I remember seeing one of his early photos on Instagram several years ago and wishing that I was still a design magazine editor and could send him to some faraway exotic place to photograph a twelve-page cover story for me.”

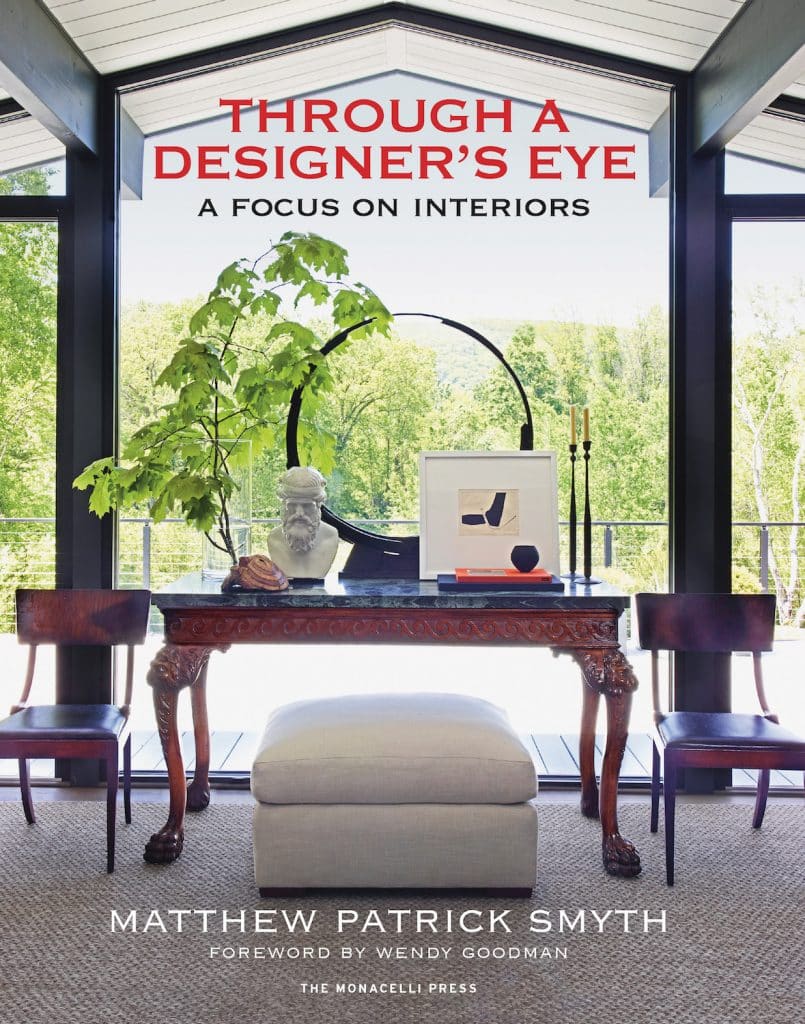

Smyth’s twinned talents are on full display in his new book, Through a Designer’s Eye (Monacelli Press), in which some of his small, square iPhone snapshots are placed alongside photographs of several of his more recent interiors, taken by Peter Estersohn, John Gruen and Simon Upton. Sometimes, the connection between the two kinds of images is obvious, as when Smyth’s close-up of two antique doors is coupled with a photo of an 18th-century Queen Anne bureau bookcase with similar decorative panels. More often, the relationship is tangential, as in the juxtaposition of a photo of a lion atop a pedestal in the Tuileries Garden in Paris with one of a reading lamp on a table.

Smyth credits Robert Wiggins, the high-school art teacher in Upstate New York who introduced him to photography in his senior year, with not only instructing him in the technical aspects of the camera and darkroom but also teaching him to question his choice of subject and frame. “He was exceptional,” Smyth recalls. “To this day, I can still hear him telling us again and again to ask ourselves who cares, when we’re considering what to shoot, and to be relentless about weeding out the unnecessary.”

The advice stuck, and although Smyth, who had considered a career in photography, wound up shelving it in favor of interior design, he readily admits that the training sharpened his eye, helping him to understand that a room, like a photograph, needs a distinct point of view. “So much of what I do as an interior designer — and so much of what I see as a photographer — is ultimately about line, form and silhouette,” he explains.

Smyth has come a long way since his time with Mr. Wiggins. Following a five-year apprenticeship with David Easton, he set up his own company in 1987 — on Black Monday, of all days. “Could there have been a better day to go out on my own?” he jokes. “I had nowhere to go but up.” And up he most certainly has gone, reaching the pinnacle of his profession. Today, in his studio on Manhattan’s Far West Side, he oversees a staff of six people, taking on about half a dozen projects a year. His work has been published in all the major shelter magazines, gracing the covers of Elle Decor and Traditional Home. He has also designed a line of fabrics and wallcoverings for Schumacher and two collections for Patterson Flynn Martin, Schumacher’s rug sub-brand.

During the almost two decades he spent setting up and running his business and establishing his design prowess, Smyth says photography got relegated to the back burner. He attributes his return to the medium to two factors: a close friendship with Gloria Vanderbilt, whose paintings and collages inspired him, and the emergence around 2007 of the smartphone camera. Since then, his phone has become a must-have tool for every design commission. He uses it to photograph raw space and, back in the office, sketches his designs on top of printouts of his shots. The camera also helps him document his progress and focus on detail, in addition to capturing images of furniture, fabrics and colors to show clients.

The 10 projects in Through a Designer’s Eye are organized into five thematic chapters with evocative titles — “The Hand,” “History,” “Surroundings,” “Drama,” “Atmosphere” — that serve as lenses through which Smyth presents his work. The residences presented are a diverse lot, including a theatrical loft with dark walls and oversize art in Manhattan’s Tribeca neighborhood (“Drama”), as well as a waterfront house with architecture by Peter Pennoyer on the East End of Long Island (“Surroundings”). There is also a historic house in Palm Beach, designed by architect Maurice Fatio, which is notable for its unique furniture and artisanal fabrics (“Hand”), and Smyth’s own Connecticut home, a delightfully imaginative redo of a neglected 1970s prefabricated deck house (“Atmosphere”).

For the living room, Smyth had a sofa belonging to the client’s mother recovered, then had the same upholsterer create a pair of complementary armchairs. A Jay Heikes drawing hangs over the sofa and a Matthias Bitzer painting over the chairs. The 1960s Charles Ramos armchair at right is from Bernd Goeckler Antiques; the table lamp is by Christopher Spitzmiller. Photo by Simon Upton

One particularly interesting project is a duplex apartment on New York’s Park Avenue that required a top-to-bottom renovation. From the moment Smyth got his first look at the place and took his first photographs, he knew the make-or-break challenge would be figuring out how to transform an awkward, unsightly staircase. The steps were squeezed in at one end of a poorly lit entrance hall and had been boxed-in with floor-to-ceiling closets. Working with architect Charlotte Worthy, he reconfigured the space to reveal the sinuous sweep of a now uncluttered and open staircase, which today adds drama and finesse to the entry and sets the stage for the cool, uncluttered atmosphere of the adjoining reception rooms.

The clients here were a couple with teenage children. They had family furniture and paintings they wanted to use but also an interest in purchasing contemporary art, so Smyth worked with them to accommodate both old and new. The wife was especially attached to a Bernard Buffet portrait of a quizzical owl that had belonged to her father. Smyth placed it center stage, hanging it over the living room fireplace. He also cut down by some inches the overly high mantle and highlighted its distinctive classical molding by scraping off layers of caked paint and rearticulating its once sharply carved motifs.

The pale blue-gray background of the Buffet painting became the inspiration for the palette not only of this space but of the entire apartment, which is soft and muted throughout. A sofa inherited from the wife’s mother, reupholstered in a sable-colored velvet, now sits perfectly at home with a group of chairs made in the same workroom where the sofa had been fabricated more than 40 years earlier. Smyth ingeniously placed recessed storage behind the walls of the traditionally furnished dining room, while striking a more modern note with a classic Eero Saarinen Tulip table in the kitchen, above which he grouped a series of Le Corbusier lithographs.

The finished apartment bears all the hallmarks of Smyth’s style: a harmonious ambience with no shouting aloud, thoughtful attention to practical details, a high degree of comfort, family antiques skillfully integrated with recent acquisitions and an engaging mixture of old and new art.

Through a Designer’s Eye has a first-person narrative engagingly written by Smyth, who uses the text to present his observations about the value of handcrafted artisanal objects as well as his love of history, drama and architecture. With gentle insistence, he conveys the importance of creating a mood and atmosphere that respond to a client’s interests and sensibility, while demonstrating how all these elements play a role in photography as well as design. The book’s greatest strengths, however, are how it helps us understand the way Smyth’s eye evolves as each interior comes together, and how it makes us see the connections between photography and design.