October 30, 2013Gimferrer, 2010. Top: The artist in his element. Photo by Xavier Forcioli. All images © Miquel Barceló/Courtesy of Acquavella Galleries

You could be forgiven for thinking that the two series of paintings currently on view at Acquavella Galleries are by different artists. But the group of dense-surfaced white monochromes and the selection of impressionistic portraits are, in fact, both by the Spanish artist Miquel Barceló, who is making his debut at the New York gallery with this elegant show, which runs through November 22. A closer look yields the realization that these works are more closely related by their surface differences than not, and are part of the artist’s ongoing engagement with both the classical traditions in art-making and material experimentation.

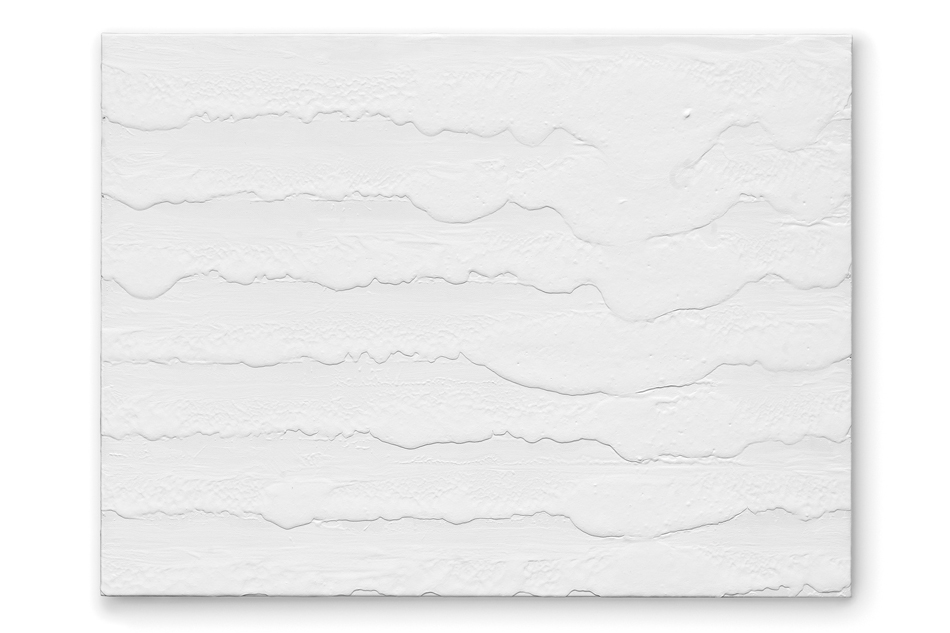

Barceló’s output is prolific and diverse. In Europe, particularly, he is well known for his ceramics — which range in scale to include small biomorphic shapes, huge urns, vases inspired by Greek pottery and even architectural interventions. (In the Cathedral of Santa Maria de Palma, in Majorca, Spain, for example, he applied a glazed ceramic “skin” to the interior walls of a chapel.) The white paintings at Acquavella approach the weightiness of these clay pieces, and are almost three-dimensional in their depth, with heavy horizontal bands of waves and target-like concentric circles that suggest aerial photographs of an achromatized desert landscape.

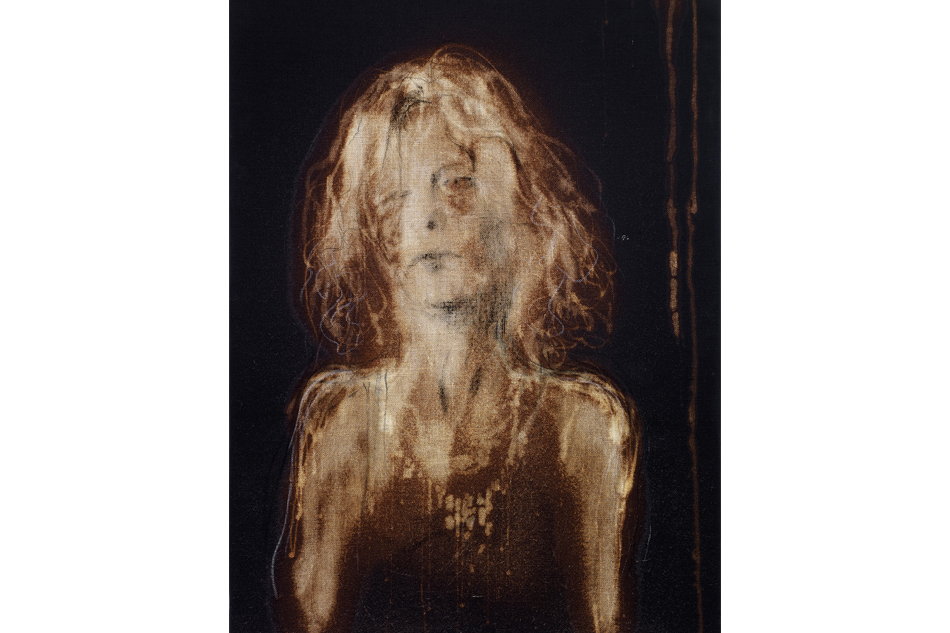

If those works speak more to Barceló’s native Majorca, whose island terrain has influenced his art, the portraits are perhaps more easily associated with Paris, his other home base. His studio there is packed with innumerable portraits of his friends and family. Over the years he has painted just about everyone he knows, including some well-known figures from the literary and artistic worlds, distorting and abstracting their features to an often-unrecognizable degree — think of a photographic negative or an overexposed image — yet conveying a psychological awareness of their characters.

Colm, 2011.

In this show, personalities include critic and art historian Dore Ashton and novelist Colm Tóibín, both contributors to the catalog; international curator Hans Ulrich Obrist; and the artist’s wife, Cécile Franken. Barceló has returned to some subjects, notably his mother, multiple times. Indeed, portraiture has a ritualistic appeal for him. “I decide I want to paint someone, and we make an appointment, and it’s always for just one hour,” explains the artist, who sketches in bleach, which creates a negative image on a black background. “It’s an hour of very strong concentration, and I work quickly.”

Despite the speedy execution, he doesn’t see anything on the canvas until later, after the solvent has gradually acted, turning the black fabric white, sepia-toned and a whole range of shades in between. “Everything that’s on the canvas is a big surprise to me,” he says, likening the chemical reaction to the photographic process. “These are like painted photography.” (He fills in the contours and works the surface with charcoal and chalk.) The portraits are a kind of inversion of the tactile, densely built-up surfaces that are typically associated with Barceló. “I use a lot of material in my work,” he says. “In this case, it’s near zero. It’s like painting with light.”