December 5, 2016Architect Nicolas Schuybroek had launched his own firm by the time he turned 30. Since then he’s worked on projects as varied as a villa in the South of France and a hotel in Chicago. Top: S House, a villa Schuybroek designed in Cap d’Antibes, was one of the first personal commissions he accepted. Photos by Claessens & Deschamps

Belgian architect and interior designer Nicolas Schuybroek is not particularly religious. Yet, many of his aesthetic influences are. From age 12 to 18, he attended a Benedictine school near Bruges. “I’m obsessed with the idea that homes should be calm,” he says. “Maybe it comes from that education.” One of his favorite sources of inspiration is the work of Hans van der Laan (1904–91), who was an architect and a Dutch monk. “He built abbeys where everything — the desks, the altars, the benches — was conceived according to a system of proportions that is almost mystical,” recounts Schuybroek.

The 35-year-old Brussels-based designer often uses the word “monastic” to describe his own work. For Schuybroek, it is important that his spaces have depth and soul. “There’s a kind of timeless minimalism to them,” he states. “I really like the notion of apparent simplicity. Very disciplined, serene interiors, which are also really warm. I also have a love of unassuming, tactile materials.”

Schuybroek has twice been named to AD France’s list of the top 100 interior designers in the world. His commissions to date have included boutiques for Bowen, the French shoe company; houses on the French Riviera, Ibiza and the Belgian coast; and several apartments in Paris. At this year’s Milan Furniture Fair, he presented two bowls for the design firm When Objects Work, which has previously collaborated with Richard Meier, John Pawson and the like. Both bowls display simple, elegant shapes and an astute mix of materials: Iranian travertine marble, Egyptian sandstone and perforated bronze, for one; lacquer and nickel, for the other.

S House, a single-story vacation home, exhibits Schuybroek’s self-described “monastic” style. Photo by Claessens & Deschamps

“Nicolas is a young perfectionist, in the positive meaning of the word,” says Beatrice de Lafontaine, the founder of When Objects Work. “Despite his age, he’s already acquired a certain maturity.” Among his other recent projects are a new showroom for the Belgian outdoor-furniture brand Tribu.

Carlos Couturier, CEO of the Grupo Habita hotel chain, hired Schuybroek and Marc Merckx to design their latest property, The Robey, in Chicago, between the Bucktown and Wicker Park neighborhoods. Housed in a triangular, Art Deco-style former office building dating from 1929, the hotel boasts 69 rooms, a rooftop terrace and pool, a street-level café and a large second-floor lounge/bar. In keeping with the slightly gritty nature of the neighborhood, Schuybroek has worked with a largely black-and-white palette. Corridors exhibiting exposed ductwork lead to sparsely decorated rooms that retain the old office doors and whose main features are large panels of industrial-style reinforced glass separating bedroom and bathroom. Couturier enthusiastically describes Schuybroek’s style as “warm, minimalist — with a twist — and sophisticated.”

Born in Brussels, where his father owned a factory that made metal packaging such as biscuit and tea tins, Schuybroek was drawn to architecture from an early age. “I was always building things,” he recalls, “whether it was Lego structures or huts in the garden. There was something fascinating about projecting myself into a world that didn’t exist.” He studied architecture for three years at the École Saint-Luc in Brussels and for a further year at McGill University, in Montréal. While in Canada, he was hired by the local architecture firm Intégral Jean Beaudoin, where he worked on two international competitions with musical connections: the Fryderyk Chopin Museum in Warsaw and the Franz Liszt Concert Hall in Raiding, Austria.

“I really like the notion of apparent simplicity. Very disciplined, serene interiors, which are also really warm,” says Schuybroek

On his return to Belgium in 2005, there was only one firm he wanted to work for: Vincent Van Duysen Architects. “For me, Vincent represents a sort of architectural truth,” says Schuybroek of his former employer and mentor. “There’s great purity to his designs.” More than anything, his time at Van Duysen’s firm instilled in Schuybroek a love of interiors and an embrace of the Gesamtkunstwerk — designing everything from the architecture of a building right down to the smallest decorative details.

The Sonkes optical shop contains marble tables with leather settees. Photo by Thomas de Bruyne

In the back of his mind, Schuybroek long aspired to set up his own firm by the age of 30. He did exactly that in 2011, after taking on his first personal commissions while still employed by Van Duysen: a loft in Brussels and a ground-up villa in Cap d’Antibes, in the south of France, which both came his way via word-of-mouth and friends. The latter is typical of his style to this day. The villa’s proportions are based on two golden sections, underscoring the importance he places on volumes. Its walls, ceilings and floors are made of either cement or concrete, showing his abiding desire to limit himself to a select palette of materials. “It helps to maintain a sense of visual tranquility,” he explains.

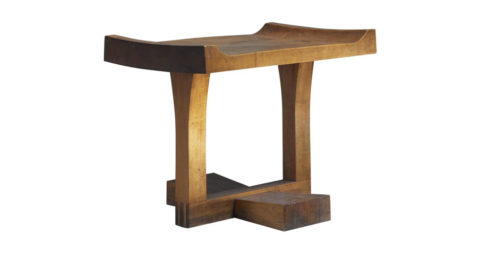

Paradoxically, the space that is least representative of his style is his own. The 1920s Brussels townhouse he shares with his wife, Gwendoline, and their two daughters, Inès and Diane, is much cozier and more traditional than the rest of his work. “I was not alone in designing it, and my wife really wanted to keep the spirit of the house,” he explains. That said, much of the furniture is similar to that which he prescribes for his clients. He loves the designs of both Jean Prouvé and Charlotte Perriand and has a particular penchant for the pieces Pierre Jeanneret created for the Indian city Chandigarh, whose urban plan and buildings were designed by Le Corbusier. “What’s really striking is how Jeanneret’s furniture was the perfect foil for the architecture,” he says. “What I love about it is both the color and the refinement of its patina.”

Once a butcher’s shop, the first floor of Schuybroek’s Brussels townhouse is now home to the offices of his eponymous firm, where he is currently working on three large ground-up houses in Belgium, several Parisian apartments, the renovation of a 1910s house near Antwerp and a contemporary extension for a private residence in Brussels. Looking forward, Schuybroek has no plans to grow much larger. “It’s not my dream to have fifteen or twenty people working for me,” he says. “I like to have a really hands-on approach. So, I’ll always want to keep things firmly under control.”

Nicolas Schuybroek’s Quick Picks on 1stdibs