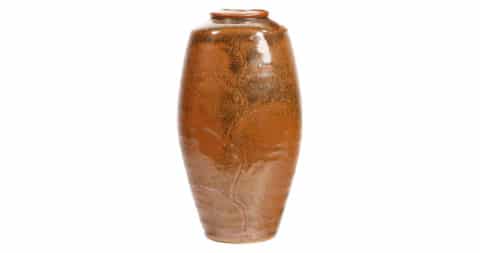

January 30, 2017Cross, 1959, is one of many ceramic works by Peter Voulkos on view at New York’s Museum of Arts and Design as part of an exhibition devoted to the mid-century sculptor’s breakthrough years (photo by Ed Watkins, courtesy of the Museum of Arts and Design). Top: Voulkos puts the finishing touches on an untitled 1956 piece in his Los Angeles studio (photo by Oppi Untracht, courtesy the Voulkos & Co. Catalogue Project).

Peter Voulkos is probably the most influential American artist you’ve never heard of. “He affected absolutely everybody in the postwar Southern California art scene, including Judy Chicago, Robert Irwin and Ed Ruscha,” says Andrew Perchuk, deputy director of the Getty Research Institute. “There is absolutely no one who knew him who didn’t hear his call, who wasn’t affected by his spirit, work ethic, intellect and engagement with a larger, broader art world.” Now “Voulkos: The Breakthrough Years,” an exhibition at New York’s Museum of Arts and Design, co-curated by Perchuk, (with Barbara Paris Gifford, an assistant curator at MAD, and the museum’s former director Glenn Adamson) is creating new buzz about the artist’s daring and genius.

Why haven’t you heard of Peter Voulkos? Because he worked largely in ceramics, a material that during the last century was relegated to the supposedly lesser artistic realm of craft. Yet although Voulkos trained as a traditional potter, he soon flouted its approved techniques, as well as its emphasis on function, transforming clay into a vibrant, highly expressive artistic medium.

His was a playful subversion. In 1956, for example, when in his early 30s, he made Rocking Pot — a milestone work comprising a large inverted bowl resting on clay rockers and jabbed with blade-like forms — as a way to thumb his nose at the pottery precept that a well-made ceramic should never rock on a table. Although wheel-throwing remained central to his work, the famously macho artist pushed the envelope by experimenting with slab building, mixing traditional glazes with unconventional epoxy paint, combining figuration with abstraction and assembling enormous sculptures that occasionally required glue to be held together — anathema to pottery purists. Always pursuing new, more expressive approaches to art, by the 1970s, Voulkos had taken his wheel (and clay) on the road, turning his masterful sculpting into performance art. Undiminished in his creative energy and manly magnetism as he grew older, the artist succumbed to a heart attack after just such a performance, in Ohio in 2002, dying at 78 practically at the potter’s wheel.

Ever an iconoclast, Voulkos made his 1956 Rocking Pot to subvert the conventional ceramics wisdom that a correctly created piece of pottery should sit solidly on a surface.

Studying on the GI Bill after World War II in his native Montana, Voulkos received a surprisingly sophisticated education in ceramics. He was exposed not only to the latest currents in Western domestic pottery, under the tutelage of such masters as Marguerite Wildenhain, but also to Japan’s burgeoning mingei (folk craft) movement, through a workshop with Bernard Leach and Shoji Hamada, two of its leading ceramics proponents. By his late 20s, Voulkos was an award-winning professional potter known for elegant dinnerware and other functional works adorned with his signature wax-resist decorations.

His growing reputation earned him an invitation to teach ceramics during the 1953 summer session at Black Mountain College, in North Carolina, from the school’s resident potter Karen Karnes. The sojourn marked a watershed for Voulkos as an artist and a teacher. He learned about Pablo Picasso’s groundbreaking ceramic experiments through the English professor M.C. Richards, an amateur potter, who’d made a pilgrimage to Vallauris, France, to see them. He also became friends with the composer and artist John Cage, along with the choreographer Merce Cunningham and artist Robert Rauschenberg. Cage was exploring how Zen might be conveyed through art not as an aesthetic, like the wabi sabi of the mingei artists, but as a technique of enlightenment to “wake up” an art audience, so to speak, to the world around it. Impressed, Voulkos became more ambitious about his own practice. His creative vision expanded further after this summer session when he visited New York and was introduced by his Black Mountain friends to some of the city’s leading Abstract Expressionists, including Franz Kline, Willem de Kooning and Philip Guston.

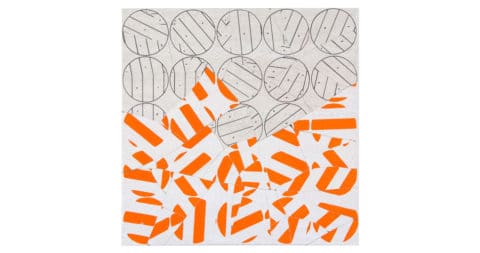

An installation view of “Voulkos: The Breakout Years,” which runs through March 15, shows off both three-dimensional and two-dimensional works, the latter exemplified by Falling Red, 1958, hanging on the back wall. Photo by Butcher Walsh, courtesy of the Museum of Arts and Design

Voulkos made this Covered Jar in 1953. Photo by Eva Heyd, courtesy of the Museum of Arts and Design

It took a few years for these experiences to percolate into his art, but the progressive, distinctly informal approach to teaching he’d witnessed at Black Mountain — more laboratory than schoolroom — directly influenced his methods when he founded the ceramics department at what became Otis College, in Los Angeles. Among his early students were Michael Frimkess, John Mason, Ken Price and Paul Soldner, all of whom went on to have major art careers. Following Voulkos’s lead, this group helped reinvent not only what ceramics could be but also what it meant to be an artist in L.A. However exciting his students found Voulkos’s brand of pedagogy, the school’s conservative administration did not approve of it, much less of how he was perverting ceramic traditions. And so, just five years after he began at Otis, the school fired him.

The more forward-looking art department at the University of California, Berkeley, recognized what a dynamic innovator Voulkos was and immediately gave him a position. In the years that followed, Voulkos profoundly influenced several generations of Berkeley art students, among them James Melchert, Ron Nagle and Stephen De Staebler, as well as the whole Bay Area arts scene. Indeed, he almost single-handedly spawned what came to be known as the California Clay Movement, which took the medium in a variety of unexpected directions, many of them pursued by his former students: Frimkess made Pop figurines and whimsical nonfunctional pots decorated with outsider-art-like imagery by his wife, Magdalena Suarez Frimkess; Mason did coolly torquing totems; Stephen De Staebler created haunting figures; and Ken Price crafted enigmatic, chromatically complex blobs.

In the 1950s, Voulkos founded the ceramics department at the L.A. institution that eventually became Otis College. His students at Otis included Paul Soldner and John Mason, who here flank their teacher at left and right, posing amid pieces from Soldner’s 1956 MFA show. Image courtesy of Soldner Descendants’ Trust

A quintet of relatively small pieces comprises, from left, Rasgeado, two untitled works and Rocking Pot, all from 1956; and another untitled sculpture, this one from 1958. Photo by Butcher Walsh, courtesy of the Museum of Arts and Design

Interest in collecting the work of Voulkos and his students has been building over the past five years. Prior to the Voulkos show at MAD, two other highly regarded museum exhibitions made the case for the vital role he and this group played in cutting-edge postwar American art: “Clay’s Tectonic Shift: John Mason, Ken Price, Peter Voulkos, 1956-1968,” at the Ruth Chandler Williamson Gallery at Scripps College, in Claremont, California, in 2012, and 2015’s “The Ceramic Presence in Modern Art: Selections from the Linda Leonard Schlenger Collection and the Yale University Art Gallery,” at Yale, in New Haven, Connecticut. In revealing these artists’ complete disregard for the “truth” of their material, and their frequent embrace of the ugly, these exhibitions also demonstrated that Voulkos and his circle presaged the preoccupations and preferences of so many of today’s creators, making them highly relatable and relevant.

A generational shift, moreover, has made more of these artists’ works available. Many of their original collectors are elderly or recently deceased, and the works from their holdings are now coming up for sale. Jeffrey Spahn, a Berkeley, California, dealer who specializes in this secondary market, says his business is brisk. “One of my greatest pleasures comes from selling a Peter Voulkos to collectors who have never bought ceramics before,” he says. “It opens up a whole new world of collecting to them.” Spahn goes on to note that in northern California, “we are often called by young collectors who live highly technical and virtual lives. They respond to the pure emotional impact of Voulkos’s work and the raw energy contained within the natural ceramic material. Clay speaks to young collectors because it’s real, it’s from the earth, and it brings them back into their bodies in a unique way.”

Considering the art historical significance of Voulkos specifically, and these makers in general, the prices for their works are extremely attractive for collectors at every level. In the 1950s, many of these creators made multiple ceramic plates, tea bowls and jars before focusing on more ambitious, and therefore less numerous, sculptural works. As a result, it is possible to acquire smaller pieces, even ones by Voulkos, for less than $3,000.

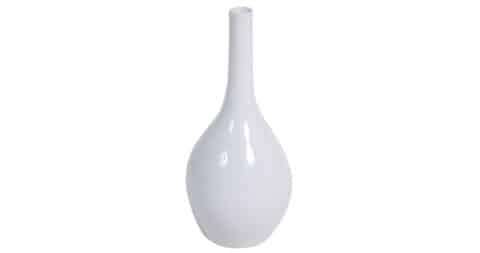

Paul Soldner is one Voulkos student at whom enthusiasts should take a serious look, advises dealer Jayson Lawfer. The owner of The Nevica Project, a gallery with venues in Chicago and Kansas City, Lawfer explains that Soldner “was a master of raku and was credited with bringing the historic Asian technique to the U.S.” He adds that “Soldner used simple techniques of throwing pottery on the wheel, but to make his sculptural forms more interesting, he also pressed burlap into the clay and stepped on it to give it different textures. We recently sold a tea bowl of his for eight hundred dollars.” Larger Soldner pieces — a spouted stoneware bottleneck vase from 1960, say, or a raku vessel from the 1970s — can be had for less than $5,000.

Voulkos works at the pottery wheel, shaping an earlier stage of Untitled, 1956. Photo by Oppi Untracht, courtesy American Craft Council Library and Archives

A striking 1973 Voulkos platter, a form that many collectors hang on their walls, may be acquired for less than $15,000 at The Nevica Project. Spahn points out that at the upper end of the price spectrum are Voulkos’s rare Japanese kiln-fired sculptures, which can sell privately for several hundred thousand dollars. (There are only about a hundred in existence.) Ken Price’s iconic blobs are also priced in the six figures, yet it is possible to acquire a limited-edition blob by him for well under $20,000.

The Nevica Project recently presented a major show of the work of Michael and Magdalena Frimkess at its Chicago venue. Just two years ago, Los Angeles’s Hammer Museum prominently featured the couple in its biennial exhibition, “Made in L.A.,” which generated a lot of press. “Their work,” says Lawfer, “is exactly what is hot right now in clay: simple and odd drawings on the pieces, jugs with holes in the vessels so the water will leak out.” He adds that “prices for the work are skyrocketing.” But they remain within the realm of reason. The mugs Lawfer showcased are priced in the $2,000 range, while large works can go for as much as $12,000.

For those who love large sculptures, few ceramic artists are as compelling as Stephen De Staebler, whose figurative works have an existential power nearly comparable to those of Alberto Giacometti. De Staebler died in 2011, shortly before the opening of a major retrospective of his work at San Francisco’s de Young Museum. Since then, De Staebler’s oeuvre has only gained in value. His San Francisco gallery, Dolby Chadwick, recently sold a piece featured in the museum exhibit, Figure with Yellow Wing, 2010, for $125,000. “That’s quite reasonable compared with so much of the sculpture I see when I travel around the world to art fairs,” says gallery director Lisa Dolby Chadwick, who is currently offering Figure with Sharp Wing, 2010, from the same body of work. “If I do my job right, the sculptures won’t be that reasonable much longer, because there just isn’t that much great sculpture out there. With every sale, De Staebler’s work grows more scarce.”

And as any economist will tell you, scarcity and desire are what drive a market.