May 29, 2022As an arts and culture journalist, I’ve been interviewing collectors for almost 30 years. One of the earliest was George Way, whose day job was as a butcher at a Pathmark supermarket. He spent much of his life sleuthing out and amassing museum-quality holdings of Dutch and English antiques, especially from the 17th and 18th centuries, and then trying to find space for them in his modest Staten Island apartment.

On the other end of the prominence scale, I’ve been lucky enough to sit with Helen Frankenthaler, Ellsworth Kelly and Frank Stella (among many other artists) and talk to them not only about their art but also about the pieces by others that they had bought, loved and lived with.

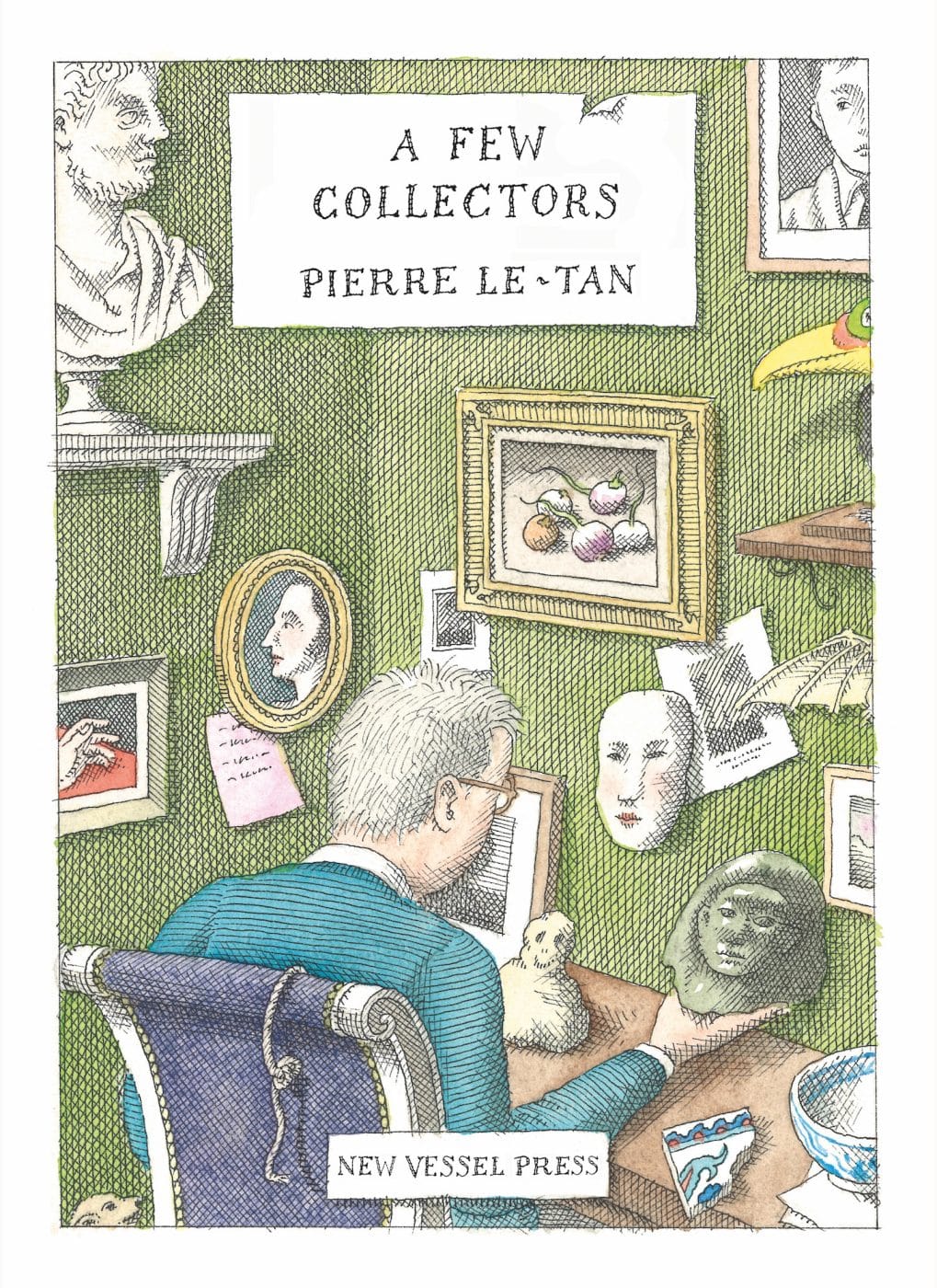

And yet I found A Few Collectors, comprising 20 profiles lovingly written and illustrated by Pierre Le-Tan, a complete revelation. Reissued by New Vessel Press, the volume is one of most charming and haunting I’ve ever read, a must-have for any collector, dealer or lover of art. It leaves a strange emotional residue, helping the reader understand the fundamental beauty and necessity of collecting while also revealing its transitory nature.

A lifelong Parisian, Le-Tan (1950–2019) was a world-renowned illustrator who created 18 covers for the New Yorker, the first when he was only 19 years old. In 2004, he had a retrospective at Madrid’s Reina Sofia. A Few Collectors, originally published in French in 2013, has now been translated into English by New Vessel’s founder, Michael Z. Wise.

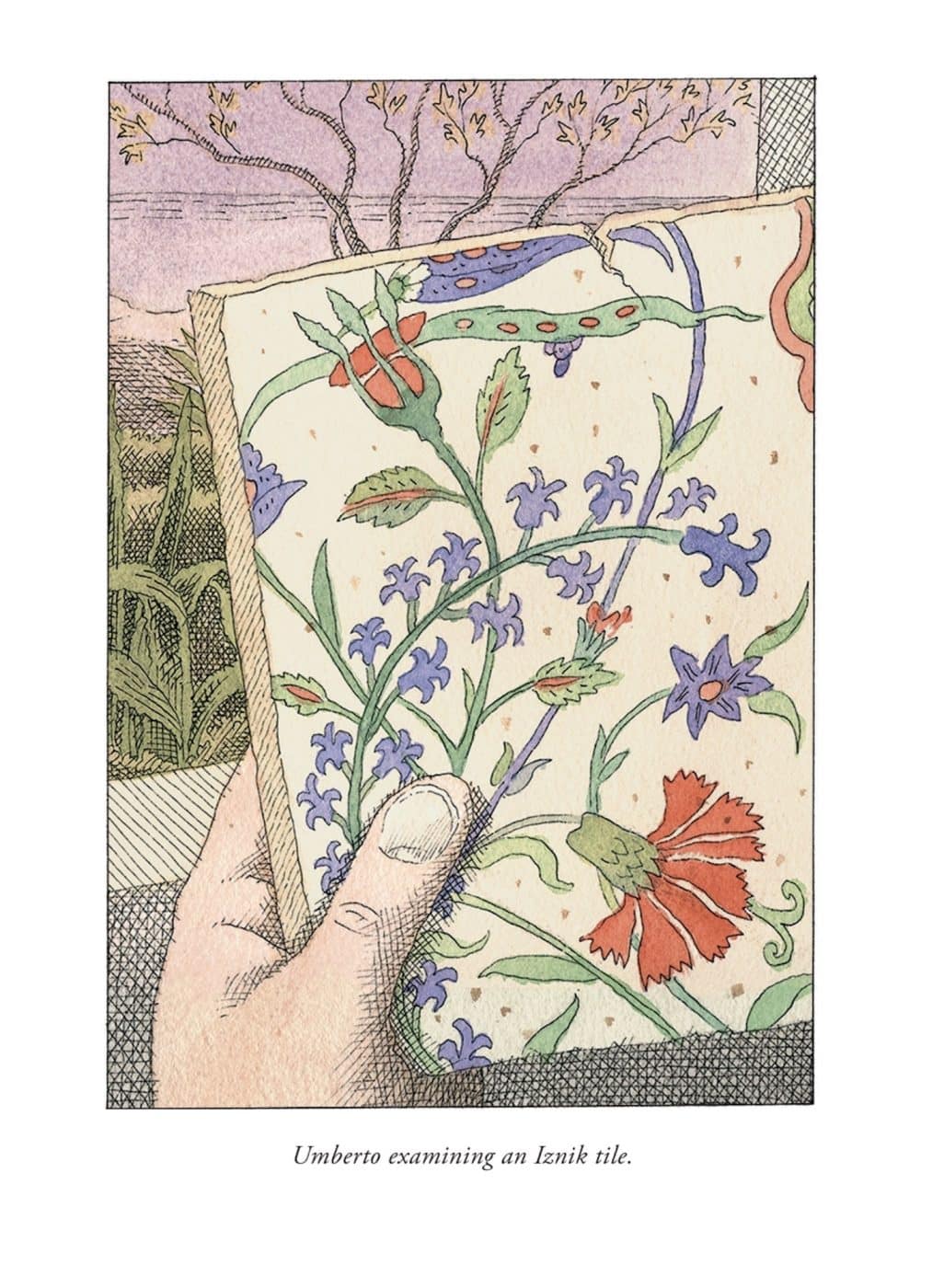

Le-Tan’s s drawings were famous among a certain set for their cross-hatching, which created a sense of refined detail. A Few Collectors demonstrates, however, that it was Le-Tan’s quirky economy with composition that truly set him apart artistically.

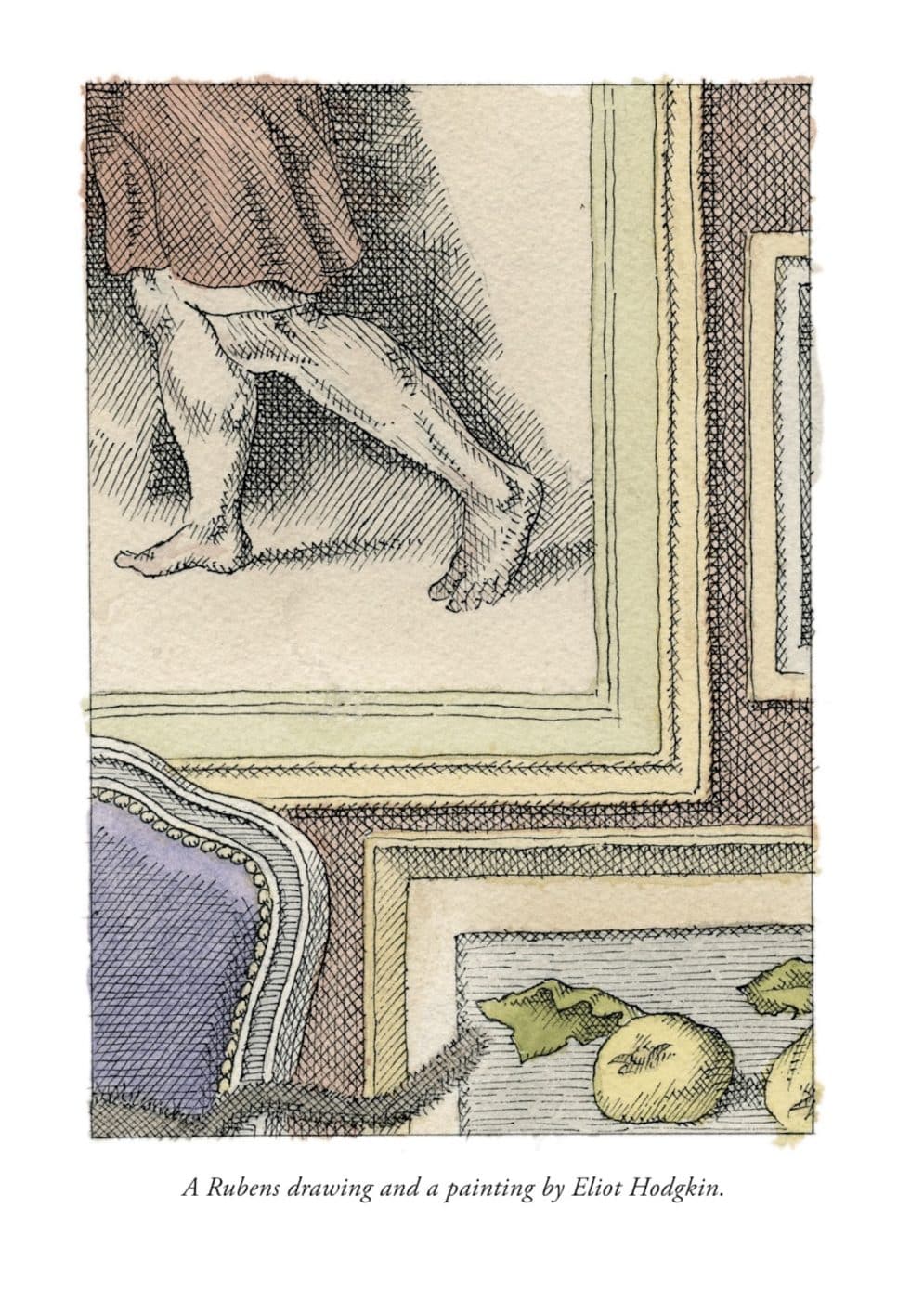

In his chapter on the London collector Eliot Hodgkin, an artist and a relative of the abstract painter Howard Hodgkin, the main illustration only partially shows the two works discussed in the text — a Rubens drawing and a painting by Hodgkin himself — along with part of a cat’s tail, presumably from a feline passer-by.

That chapter — Le-Tan is as concise a writer as he is an illustrator, so they’re all fairly short, mostly 10 or so paragraphs long — contains a sentence subtly hinting at the book’s organizing principle. “So many collections are mere accumulations created by chance or wealth,” it states, implicitly pointing to the author’s own contrasting focus: the small set of collectors who break that mold. Passion, with all its inherent irrationality, is what attracts Le-Tan. The book contains just one person the reader might be expected to have heard of: Pierre Rosenberg, a former director of the Louvre who collected Murano glass, referred to in the book only as “Pierre R.”

Certainly, the opening chapter gives the reader the idea that this will not be a normal set of collector profiles. Consider the Schenker-Angerers of Paris. The wife bore the title the Princess of Brioni, having descended from royalty associated with an archipelago off the coast of what was then Yugoslavia. The noble family, however, had fallen on hard times and had to sell off almost everything they owned.

So, Le-Tan depicts the faded rectangles on the wall where great pictures once hung and recounts his conversation with the couple, who talked about each empty space as if the work were still there. (Only one piece remained, an 18th-century drawing in the style of Tiepolo.)

At the end of the brief text, he notes that the princess had put her false eyelashes on backwards. But Le-Tan is not out to make fun of his subjects. He says they covered her eyes in a “charming latticework.” The point is that the quality that made the collection special, the acquirers’ love and devotion, remains, whether or not the paintings are physically present.

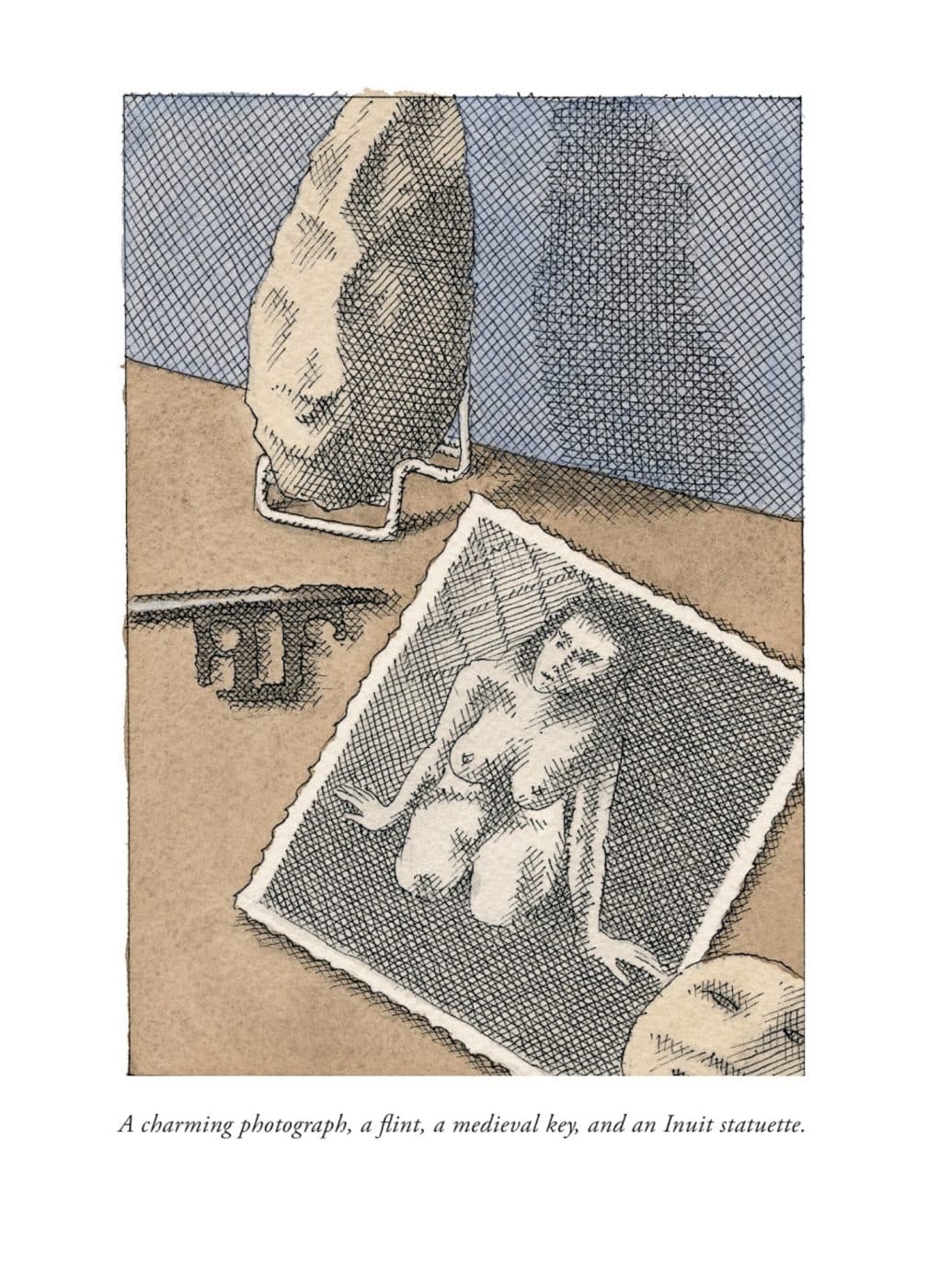

Le-Tan doesn’t have to like the collector or the collection to include them in his book. Describing, for example, the eclectic trove of a subject he calls only Edouard M., which somehow encompassed a nude photo of an actress and a model of a warship, he notes, “None of these objects left you indifferent.” For Le-Tan, that’s enough. In the Paris home of Jacques Bixio, he discovers a massive collection of dolls that, he writes, had “invaded the rooms like cockroaches.” He makes up an excuse to leave, “feeling oppressed” by the dolls’ eyes.

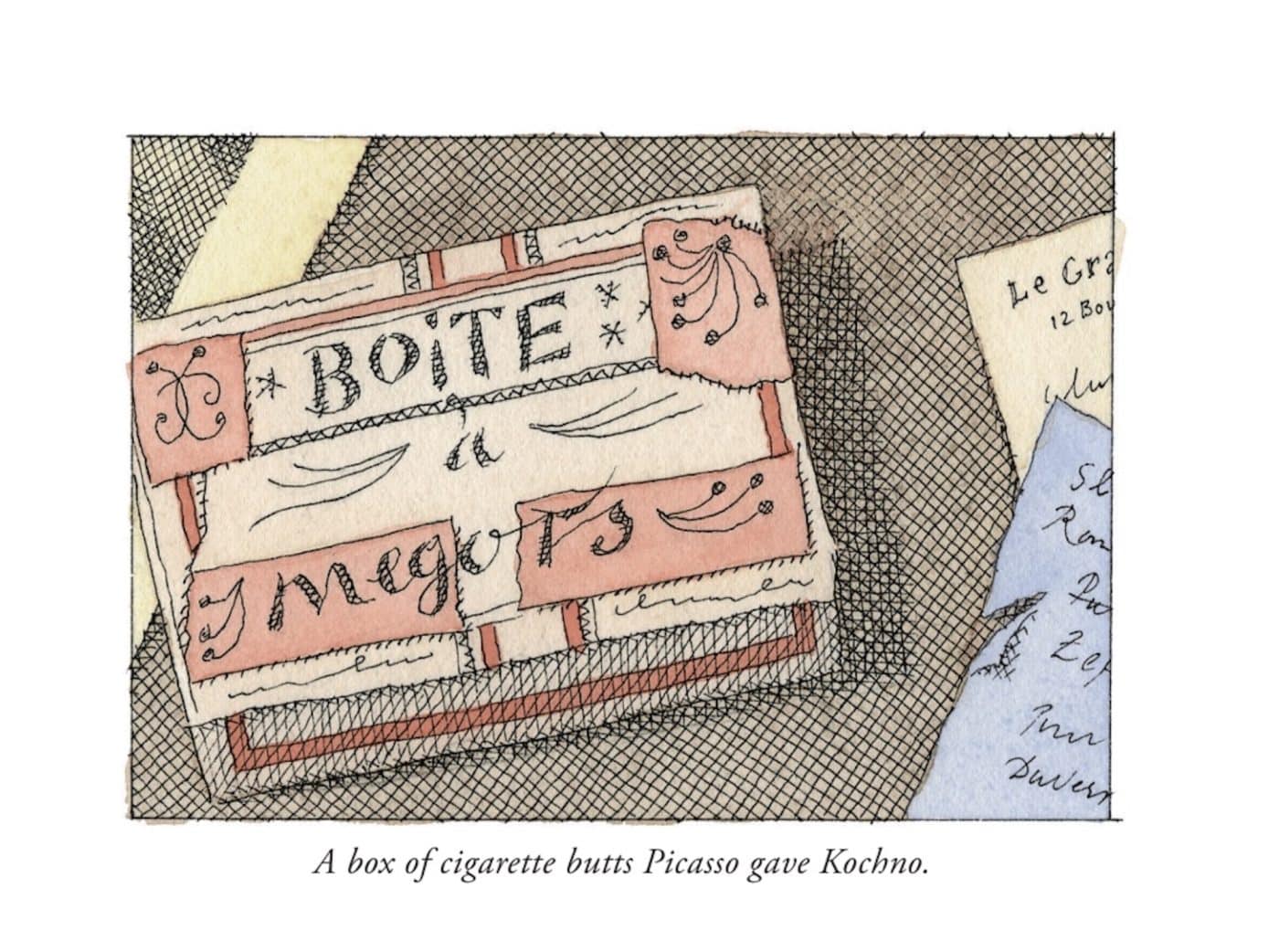

The unusual is celebrated, as is quirkiness taken to an extreme. Pedro Duytveld, whom Le-Tan meets on a train, turns out to collect, if you can believe it, crumpled-up pieces of paper. Based on Le-Tan’s drawings, Duytveld annotated them with a date and other identifying pieces of information. It seems that for him, it was a way of marking time, perhaps akin to the Japanese conceptual artist On Kawara’s simple calendar dates painted against plain backgrounds.

It won’t surprise readers to learn that Le-Tan was a collector too, and a fairly serious one. He even gives himself a chapter. Le-Tan’s personal Rosebud was a tobacco box, obtained when he was a young child; he depicts himself with his prized first trophy. He tells us he has acquired thousands of objects — from furniture by Jean-Michel Frank to drawings by Lucien Freud — and that, at the time of the writing, he no longer owned most of them.

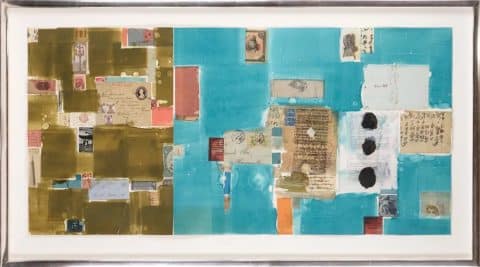

Collecting is “both essential and completely useless,” writes Le-Tan, and somehow also “the only sport that suits me.” In 1985, he sold his Surrealist and neo-Romantic paintings at Sotheby’s London; he’s the rare artist to lovingly draw the cover of his own auction catalogue, shown in this book. (In March 2021, there was a posthumous sale of his holdings, also at Sotheby’s.)

The true theme of A Few Collectors is that we are mere temporary caretakers of the objects we accumulate. As Le-Tan puts it in a caption to a work he had to sell, a self-portrait by the Japanese painter Toshio Bando, Sic transit gloria mundi — “Thus passes the glory of the world.” Now that Le-Tan has died, the phrase is doubly poetic.

But the takeaway from this strange and gorgeous volume isn’t that we shouldn’t collect. It’s that we can’t help but collect, and we should do so with humility and a gentle grip on the pieces that come into our lives.