November 27, 2017Judith Gura’s new book celebrates the aesthetic movement that reinjected ornament and a sense of joy into design after an era ruled by the stripped-down International Style. Above: Works by the Italian postmodern collective the Memphis Group fill a Dallas living room around 1985 (photo © Lorry Dudley). Top: The Netherlands’ Groninger Museum, completed in 1994, has pavilions by four architects overseen by Alessandro Mendini (photo © Ger Bosma/Alamy Stock Photo).

How about writing a book on postmodern design?” When Lucas Dietrich, of Thames & Hudson, posed that question to me a couple of years ago, my first thought was that it was an ideal subject, and my second was that I’d have to get started immediately. I could already see that after three decades in limbo, postmodernism was definitely making a comeback.

I’d always thought of this particular aesthetic movement as an interesting, though short-lived, aberration in the history of design. I’d made pilgrimages to a number of postmodern buildings (liked some, was indifferent to others) and even attended a couple of Memphis Group furniture presentations back in the 1980s, but I hadn’t given it much thought for some time.

Then, on a trip to London in 2011, I visited the Victoria and Albert Museum to see “Postmodernism: Style and Subversion, 1970–1990,” a survey of art, design and architecture during those explosive years, and I began to think I’d missed something. Seen from a 21st-century perspective, this provocative movement, which challenged the establishment and brought ornament back to architecture and design, seemed worth investigating anew. I started to notice more postmodern pieces coming up at auction and in design galleries, and more unconventional shapes, extroverted colors and lively patterns in new furniture and fabrics, and I realized that modern design was no longer being defined only by the International Style. It had become more eclectic, more inclusive and not quite so serious. Postmodernism, I thought, surely had something to do with that.

In 1985, Memphis founder Ettore Sottsass and his associate Aldo Cibic designed the interiors of the Venice home of Italian producer and design editor Cleto Munari and his wife, Valentina. “Throughout the apartment,” Gura writes, “embellished doorways serve as wall decor.” Photo courtesy of Cleto Murari

Sottsass’s ceramic Yantra Y33n vase from the 1960s is currently on offer at Somewhere Tokyo.

Mendini and Alessandro Guerriero created this three-panel screen — now available through Galerie Lumières — in 1988 for Studio Alchimia’s Ollo Collection.

I signed the contract to write the book in April 2015, then completed the first sections at the end of August the following year and the final material in December, which is a pretty quick turnaround. The chief theorist of the style, Charles Jencks — whose 1977 book The Language of Post-Modern Architecture went into seven editions — generously agreed to write a foreword, several specialists willingly contributed essays, and architect Denise Scott Brown signed on to do the afterword, all of which made me sure postmodernism was the right subject at the right time.

And now, this very week, Postmodern Design Complete — the publisher’s title, not mine; I don’t think it’s over yet! — will make it onto bookstore shelves just in time to help celebrate Memphis Group founder Ettore Sottsass’s centennial this year.

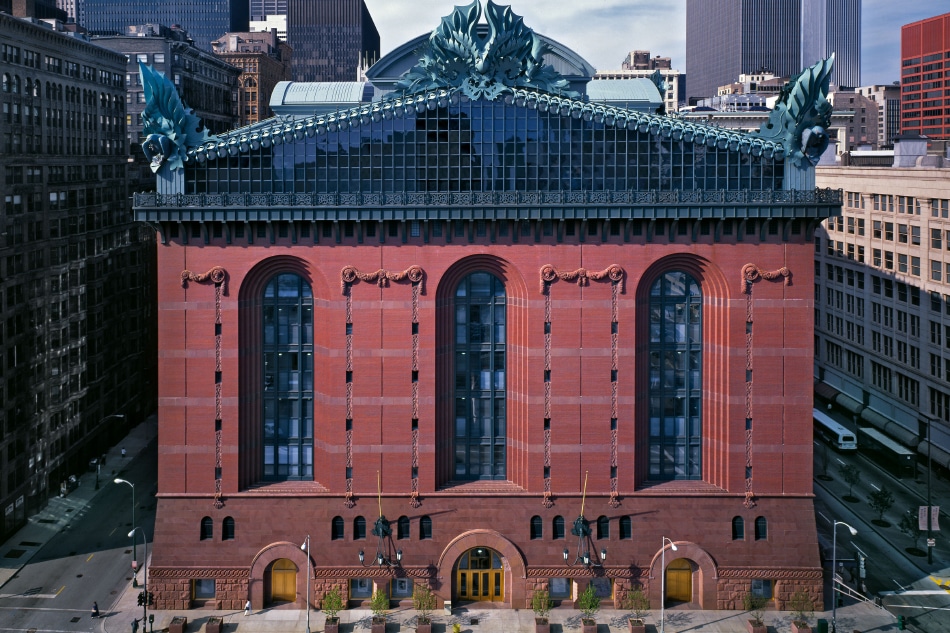

Choosing the first group of architects and designers to include in the book was easy. Robert Venturi and Michael Graves had designed the most attention-getting buildings, including the former’s 1964 Vanna Venturi House, in Philadelphia, and the latter’s 1982 Portland Building, in Portland, Oregon. And Sottsass and Alessandro Mendini had created some of the most iconic furniture: for example, Sottsass’s Carlton bookcase and Mendini’s Proust chair. The others fell into place after that. Some selections — like Mario Botta, Arata Isozaki, Charles Moore and Robert A. M. Stern — came immediately to mind. (Moore’s exaggerated iterations of classical details in his own California home and Stern’s urbane use of traditional architectural elements in interiors that are innovative without being jarring are two directions along the same postmodern path.) Other, less familiar, names included Bořek Šípek, Aldo Cibic, Oscar Tusquets Blanca and Tomás Taveira, whose 1989 BNU bank in Lisbon combines massive columns and contrasting color for traffic-stopping impact. A few resisted (“He was not a postmodernist,” asserted Richard Meier’s representative), but altogether, these leaders of the movement, a definitely international mix, proved very cooperative and diverse in attitude.

For me as a historian, one of the most interesting parts of researching postmodernism was that a lot of the designers are still living. Through phone and in-person conversations and the convenience of email, I was able to connect with many of them directly, helping me understand their motivations and the origins of their designs. Nigel Coates, for example, saw architecture as more experience than object, and as a result, he designed his interiors with theaters and nightclubs in mind. John Outram, meanwhile, believed all possible building forms had already been designed, so he made up his own witty variations on classical columns and capitals. And when I decided to include graphic design, I learned from innovators like David Carson and Ed Fella about how working in what was at that point a relatively new profession had given them freedom to experiment with mixing typefaces and departing from then-standard grid-pattern layouts.

Gura writes that “the grand, sparsely furnished salon,” of Mendini’s Casa della Felicità, near northern Italy’s Lake Orta, features “rounded walls and arched floor-to-ceiling windows.” Sottsass designed the fireplace. Photo courtesy of Alessi, © Aldo Ballo

Mario Botta designed his Seconda chair in 1982 for Alias. It is available through the Modern Archive.

Sottsass’s Alaska vase for Memphis, now on offer through 1000 Objekte, also dates to 1982.

Postmodern design is often described as simply a reaction against the International Style, but I found the story to be more complicated, and much more interesting. Venturi’s 1966 book Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture and his 1972 Learning from Las Vegas, written with his wife, Scott Brown, and Steven Izenour, proposed that architecture needed to be more varied, to communicate with its users and to embrace historical and vernacular elements. Early structures, like Moore’s 1978 Piazza d’Italia, in New Orleans, with its vivid colors and classical columns, and Philip Johnson’s 1984 AT&T Building, on New York’s Madison Avenue, with its Chippendale-pediment top, reintroduced ornament to architecture and presented the public with a provocative new aesthetic.

To many people, however, postmodern design is synonymous with the Memphis Group. This Italian collaborative created the most radical and attention-getting work of the period, upending most of the accepted standards of how furniture should look. It began with a coterie of young designers who gathered around Sottsass and, in a legendary Milan meeting, determined that all the new furniture they were then seeing was boring. In response, they decided to design, produce and market their own collection, one that wouldn’t be restricted by concerns like functionality and so-called good taste. Its debut, at Milan’s 1981 Salone del Mobile, drew thousands of viewers and caused a major stir in design circles. Reading archival documents and newspaper reports from the period, I found that everyone had opinions about the Memphis pieces. Most of them were negative, including that of Suzanne Slesin, who described them in the New York Times as “an outrageous collection of bizarre colors and shapes.” But Paul Goldberger, the following year, viewed the work as “wild and wonderful,” and Michele De Lucchi, one of the original members of the collaborative, recently recalled seeing 52 magazine covers featuring Memphis in the first six months after Salone.

Aptly located in Memphis, Tennessee, the home of photographer Dennis Zanone contains what Gura describes as “one of the

most impressive collections of Memphis furniture extant.” He’s been acquiring the pieces since 1984, when a show of the works came to the local Brooks Museum of Art. Photo by Zanone Photo

The Modern Archive is offering a 2015 reissue of the Kristall table, created by Michele De Lucchi for Memphis’s debut collection in 1981.

Another piece from the premiere Memphis line, this reissue of Martine Bedin’s Super lamp is also available from the Modern Archive.

Thames & Hudson will release Postmodern Design Complete on November 28.

Notwithstanding the fact that people were reading and talking about Memphis, finding interiors into which the furniture could fit comfortably proved to be something of a challenge for designers — and I struggled to find images of interiors that showed the furniture in situ. Postmodernism doesn’t mix easily with other styles, and there were relatively few people who bought, and furnished their homes with, many of the pieces — Karl Lagerfeld and David Bowie being two prominent exceptions. But designers like Stern, Stanley Tigerman and a few others managed to translate a postmodern aesthetic into livable buildings and interiors, and showing their work in the book helped me illustrate the flexibility and variety of the style.

I’ve seen comments that the recent revival of interest in postmodernism reflects the parallels between that era and today, both periods being fraught with cultural conflict, economic uncertainty and political malaise. There may be similarities, but I think the reasons for its renaissance goes beyond that: Postmodernism opened up a range of possibilities for designers, and they have since enjoyed the freedom to experiment with new ideas, new materials and new forms without being dismissed as foolish or unrealistic. Added to that is interest in the movement from a millennial generation that never, for the most part, saw the work when it was new. Many of these people are now enthusiastically accepting, and collecting, it.

A while back, early Memphis collector Al Eiber told me that “part of the fun is buying this stuff before everyone else likes it.” Sadly for Al, his fun is now (long) over — and the release of Postmodern Design Complete is probably not going to help.

Shop Postmodern Design on 1stdibs