January 15, 2022Hear the word Surrealism and you’ll almost certainly picture iconic paintings by René Magritte, Salvador Dalí and their cohort. But Surrealism also had a life in three dimensions, as in Dalí’s sofa based on Mae West’s lips and phone with a lobster shell for a receiver. (His client for those objects was the British arts patron Edward James, who also installed carpet bearing his wife’s footprints in their phantasmagorical weekend house near Oxford.)

More recently, designers like Gae Aulenti, Philippe Starck and Gaetano Pesce have brought Surrealist tropes — including extreme plays of scale and out-of-context body parts — to furniture, accessories and sometimes whole interiors, most of them for wealthy and eccentric patrons.

Sadly, few Surrealist rooms — even the most recent ones — survive. In the early 1990s, Pesce designed a Manhattan office for the Chiat/Day advertising agency that, in the words of the New York Times architecture critic Herbert Muschamp, appeared to be “suspended in a dream state: tables sprout faces, chairs chime, the floor erupts in a free association of icons — arrows, animals, eyes, logos, light bulbs.”

But not every Chiat/Day employee enjoyed what one of them described as “working inside a migraine.” The interior was dismantled after just a few years, and its components — out of context but at least intact — are sought-after collectibles: a desk with an oddly shaped resin top, a mobile workstation right out of Mad Max and a door bearing a giant handprint.

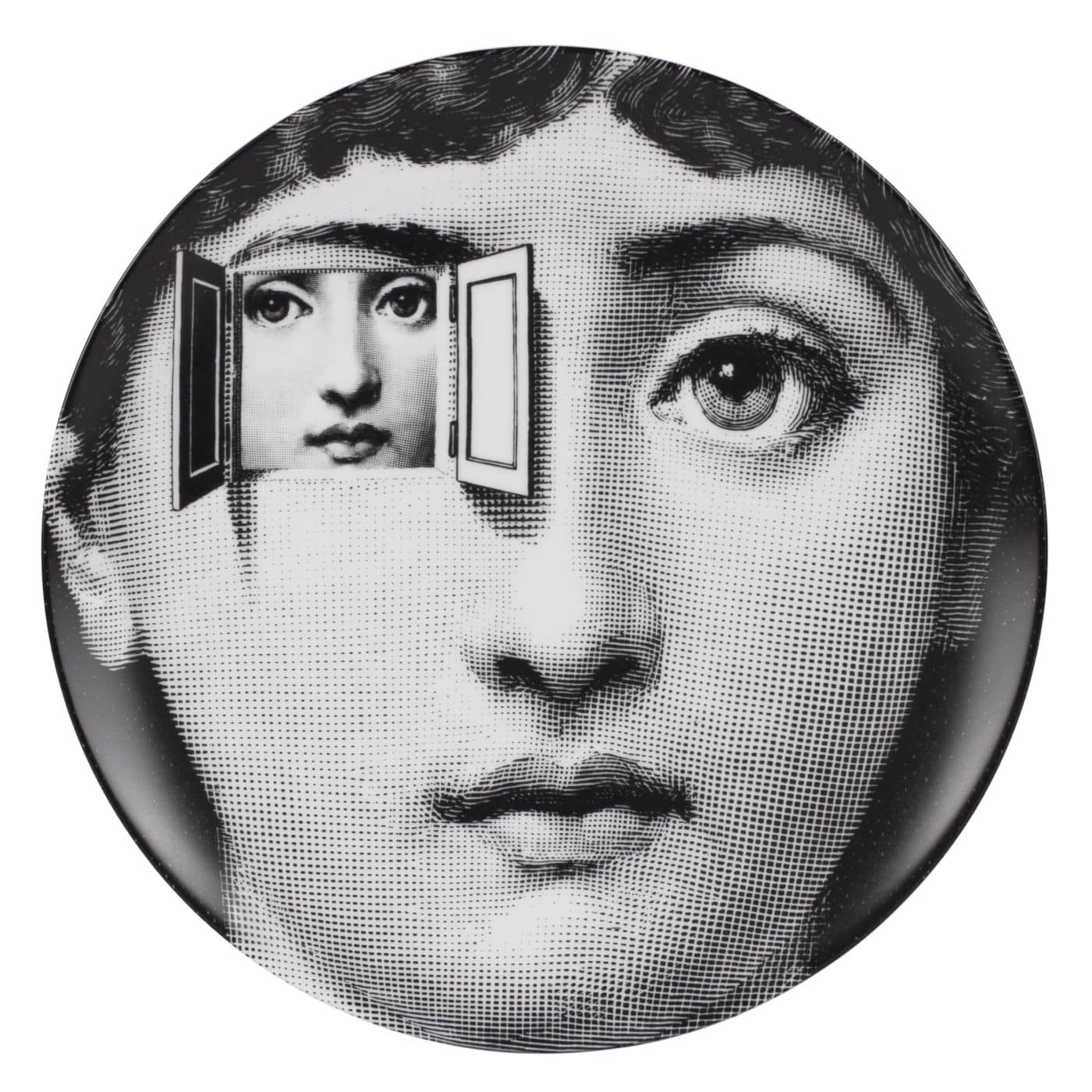

No such luck for the Surrealist elements of the ocean liner Andrea Doria, including one stateroom designed by Gio Ponti and covered entirely in zodiac symbols by the great artist and illustrator Piero Fornasetti. The ship sank in 1956 off the coast of Nantucket as the result of a collision, not with modernism but with another ship.

“Objects of Desire: Surrealism and Design 1924–Today,” at the Design Museum in London through February 19, uses vintage furniture and lighting, as well as drawings, photos and silent films, to resurrect the great Surrealist interiors, including James’s Monkton House and even a Paris apartment designed in part by the form-follows-function-not-fantasy proponent Le Corbusier.

The show (whose originators, at the Vitra Design Museum, are hoping to find it a venue in the United States) contains many contemporary pieces, like Nina Saunders’s chair with a basketball-size protrusion rendering its seat unsittable and Moooi’s full-size metal horse with a lamp implanted in its head. These recent works are inspired by Surrealism but seem far removed from its roots, which included Freud’s writings on the unconscious. Sometimes, a cigar-shaped sofa is just a cigar-shaped sofa.

Forming something of a sprawling Surrealist interior itself within architect John Pawson’s minimalist museum, the exhibition is a delight for the senses. Does it need to be more than that? Its curator, Kathryn Johnson, writes in the companion volume, Surrealism and Design Now: From Dalí to AI, “Surrealism was in part a reaction to the horrors of the First World War and the 1918 influenza pandemic. Today, in the context of dizzying technological change, war and the Covid-19 global pandemic, the Surrealist spirit feels urgent and relevant once again.”

And yet, the Dalí-Magritte era of Surrealism developed before AR and VR promised fantasy at the touch of a button. In fact, the critic Jonathan Jones writes in the Guardian, the Design Museum show doesn’t make a case for Surrealism’s recurrent relevance but rather “makes you see with great clarity how extreme and extraordinary this movement really was.” Today, when eclecticism rules the design world, it’s one style among many. The Surrealism of the early 20th century, Jones writes, is “not the parent of today’s playfulness but something infinitely more serious and revolutionary.”

So, perhaps today’s Surrealism is only skin deep. And yet, in tough times, isn’t playfulness enough?