June 18, 2023There is a lot of chatter at the moment about quiet luxury. The kind of pared-down interior design that whispers wealth and sophistication through exquisite materials and exacting craftsmanship. It may be the new look to have right now, but is it enduring? That, for us at 1stDibs, is the ultimate definition of luxury. We think both yes and no.

Quality endures even as decorative looks come and go. Which is why, for those who aspire to true luxury, we suggest assembling a home filled with quality pieces reflective of you — your taste, your lifestyle. When done well, even audacious and irreverent mixes of furniture and art will ultimately be deemed rooms of timeless luxury.

How we think about luxury today has a lot to do with the taste trailblazers of a century ago, the pioneers of the modern era in 1920s Europe, especially Paris, when there was a new emphasis on the individual and human invention. One of the period’s originals, and perhaps its greatest oracle on matters of style and luxury, was Coco Chanel.

Yes, Mademoiselle had her moral flaws, but she was an undeniable liberator. Her simplified silhouettes freed women from corsetry and froufrou so that they might be seen for themselves. Donning her innovative early creations meant having the courage — and confidence — to reject convention. “Elegance is refusal,” she pronounced.

Chanel’s own confidence, authenticity and disciplined yet curious eye made her Paris apartment as remarkable as her clothes. Indeed, motifs from its decor continue to inspire Chanel designs to this day.

A study in baroque splendor, the golden-hued rooms brimmed with ornately carved furnishings, superb antique mirrors and Coromandel screens, elaborate crystal chandeliers of her own design and rows and rows of beautiful leather-bound books. Yet the apartment was not showy but intimate.

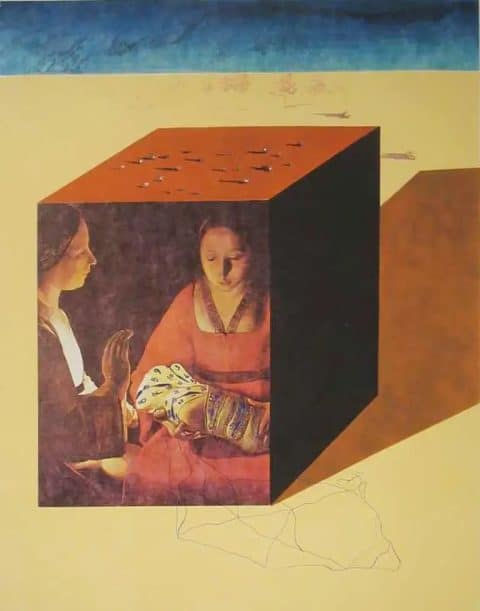

Many of the artworks and objets on display were gifts from artist friends and lovers. Salvador Dalí painted a picture of a “lucky” shaft of wheat as a charm for the superstitious Mademoiselle. Alberto Giacometti sculpted a golden hand expressly for her. An antique Russian icon was a present from Igor Stravinsky.

Silver cigarette cases lined with gold were tokens of love from the Duke of Westminster. If these bibelots and other rare and exceptional pieces represented luxury, it was of a very particular sort — one with personal meaning. “Luxury for oneself” is how Chanel put it.

Jean-Michel Frank was a contemporary of Chanel and arguably the most radical interior designer of his day. You might call him the man who invented “quiet luxury,” crafting as he did environments of austere opulence for the ultrawealthy.

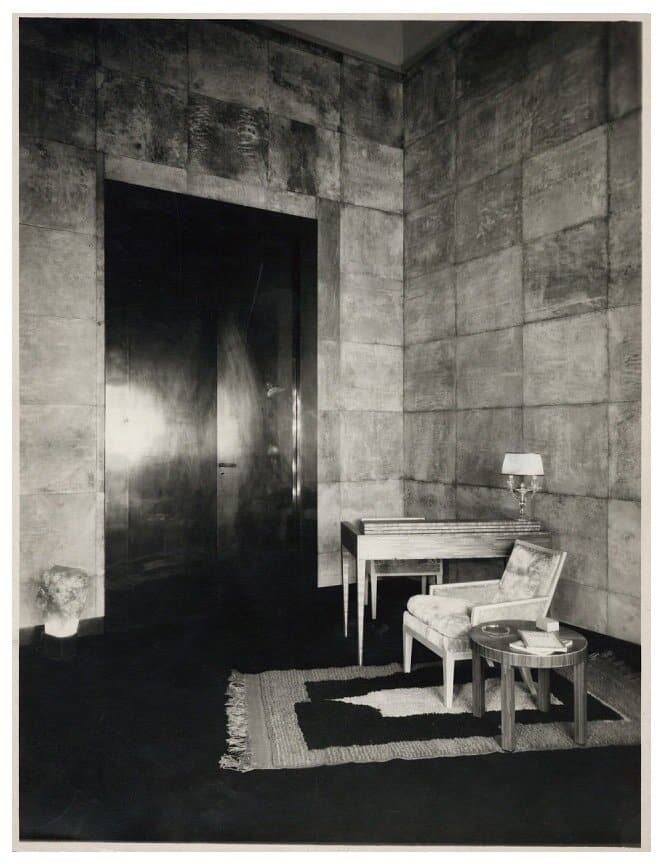

In 1925, he caused a sensation by “unfurnishing” a series of sumptuous rooms in the magnificent 18th-century Parisian hôtel particulier of Charles and Marie-Laure, the Vicomte and Vicomtesse de Noailles, who were great patrons of the Surrealists. The rooms were stripped of their ornate moldings, with the walls tiled in parchment squares and the carved doors replaced by slabs of unadorned bronze.

While the furnishings Frank designed were classic in their geometric simplicity, exquisite proportion and superlative artistry, they were fashioned out of materials so lavish and unexpected as to verge on the surreal.

The fireplace surround was clad in mica; low tables were sheathed in lacquer and shagreen; and a console was covered in straw marquetry. The seating, amply upholstered for comfort — then a new priority — was outfitted in creamy white leather. Frank’s palette may have been limited to pale neutrals, but the luxury connoted by those hushed tones resounds to this day.

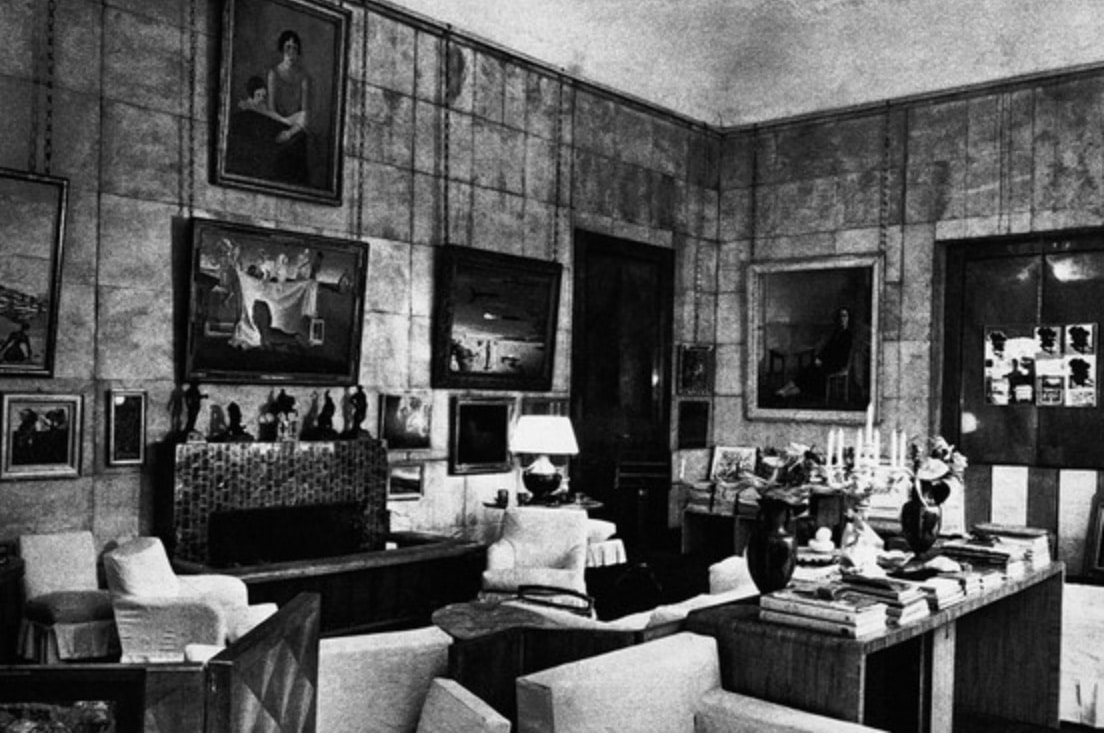

What’s most intriguing about Frank’s revolutionary decor, however, is what became of it. After a few years, the formidable Marie-Laure chose to “re-furnish” the rooms with some of her antiques and to hang more avant-garde paintings from her collection on the walls — Frank had permitted only three works, by Dalí, Joan Miró and Pablo Picasso.

On the various tables, she displayed curios and placed stacks of books and magazines. The clutter imbued the interiors with her vivacity and interests. Yet the rooms remained utterly chic, a testament to the good bones of Frank’s original design.

Curiously, for all the influence Jean-Michel Frank had on the world of high design until his untimely death, in 1941, he was quickly forgotten. Yves Saint Laurent revived his reputation in 1970, when he and Pierre Bergé moved into a Left Bank apartment believed to have been designed by Frank.

Although Saint Laurent revered Frank as the ne plus ultra of Art Deco designers, he could not subscribe to a purist vision; his own tastes were too promiscuous.

Instead, he filled his apartment with furnishings by Frank and his contemporaries, like Pierre Chareau, Jean Dunand and Émile-JAcques Ruhlmann, all known for designs of remarkable sophistication and workmanship.

He interspersed those pieces with ancient Roman marble torsos, Italian Renaissance bronzes and the whimsical fauna of his friends Les Lalannes. The apartment’s magisterial mix of works of different styles and periods, all of impeccable pedigree, was immediately celebrated as the epitome of timeless luxury.

And so it remained, even when, because of Saint Laurent’s obsessive collecting, every wall and surface became a muddle of masterworks more evocative of the belle époque in display than the modern. After his death, when his collection went on the block at Christie’s, it shattered auction records, with pieces selling for double and triple their estimates. That’s the power of style combined with provenance when it comes to luxury.

While the appreciation for a designer or style may ebb and flow, works of outstanding quality always prove their worth over time. This is a principle well understood by the esteemed Belgian interior designer, curator, author and gallerist Axel Vervoordt, who first made his name as an antiquaire by buying against trend.

Vervoordt not only had a genius for spotting what would become highly valuable but also knew how to arrange his treasures in sparse settings, so that his clients could discern for themselves their essential qualities. This might mean putting rustic and baroque furnishings in conversation or placing ancient statuary with modern paintings.

After becoming a student of Eastern philosophy, he recognized that the aesthetic polarities he was creating were material expressions of Zen koans conveying ineffable truths through paradox.

The rough-hewn folk furniture he so loved was expressive of wabi sabi, the Japanese notion that true beauty resides in imperfection. Through these erudite discoveries, he developed an aesthetic of the universal, finding in the raw and the refined, in vignettes that might combine humble Japanese ceramics with stunning works by Miró and Mark Rothko, an affinity that was always of the moment, always timeless.

Quiet luxury may be currently covetable, but volumes more can be spoken by a collector with a cultivated and confident eye. That’s a luxury that will be heard and appreciated for years to come.