May 20, 2018While most of Europe was stuck in artistic stasis during the Middle Ages, the indigenous peoples of the Americas were experiencing a diverse cultural explosion. Today, these pre-Columbian civilizations, with their beguiling pottery, architecture and sculpture, continue to inspire contemporary artists and designers. Modern makers fashion the same raw, imperfect shapes and practice the traditional techniques utilized long ago — from engraving silver to clay-brick making — and reimagine them for their own works. The result is an interplay between ancient and new, a conversation across centuries. Here, we highlight three creators influenced by pre-Columbian art whose works are rooted in the past but exude a modern allure.

Chris Wolston

Chris Wolston, who has studios in Brooklyn and Medellín, Colombia, created a series of terracotta chairs with planters in their backs in an effort to make functional art (portrait by David Sierra). Top: Details of Múcura by Alexandra Agudelo (photo by Juan Manuel Aguayo, courtesy of Cristina Grajales Gallery), a terracotta planter chair by Wolston (Clemens Kois for Patrick Parrish Gallery) and a Salome dining table by Aguirre Design (photo courtesy of Aguirre Design)

The craft of Rhode Island–born designer Chris Wolston, despite the postmodern appearance and multifunctional appeal of his objects and furniture, is rooted in the ancient. Wolston translates to his own work traditional processes for making everyday items like lemon presses, bricks and meat hammers, tracing them back to their origins and often traveling to remote areas of the world where the objects are still molded by hand.

Wolston’s primary workspace is nestled within the Brooklyn Navy Yard, but his practice is heavily influenced by his relationship to Medellín, Colombia, where he maintains a second, smaller studio on a mountainside just outside the city. He first arrived in Medellín as a Fulbright scholar, working with the University of Antioquia’s pre-Columbian ceramic archive, and it is there that Wolston sources clay for an ongoing series of terracotta chairs emblematic of what he calls “relational sculpture.” “After a while, it seemed like such a waste to make sculpture that would just sort of sit there and with which you couldn’t interact,” he explains. “I like the idea of shifting that material practice toward these things that people can interact with and then actually have a new way of relating to the material.”

These terracotta seats feature thumb-printed textures that reference the unintentional impressions left in brick by the errant caress of a Colombian brickmaker’s hand smoothing the clay as it dries in a wooden mold. “It was a recontextualization of the material that all the homes [in Medellín] were built out of, taking that material and putting it back inside the house,” he says. “Even now when I go down there, as I walk around the city, I’ll see brick walls with these hand marks on them.” Generally, Wolston keeps the natural burnt-orange hue of the terracotta. In some instances, however, he paints the pieces in exuberant shades, like metallic pinks and greens. Many of the chairs feature planters sculpted into their backs, a playful element intended to evoke inexpensive everyday terracotta flowerpots, to which Wolston feels everyone can relate.

Wolston recently returned to Medellín to put the finishing touches on a new series of furnishings, including the Orgy table, composed of entangled sand-cast-aluminum legs and appendages puzzle-pieced together. Made of metal taken from discarded motorcycle engines, pots and pans — anything he can get his hands on — and melted down, the objects feature in a just-opened solo exhibition at the Future Perfect in New York that runs through June.

Aguirre Design

Mauricio Aguirre channels nearly 30 years of design industry experience in artfully conceiving chic sculptural furniture and objects. Through his New York–based firm, Aguirre Design, founded in 2003 and a 1stdibs New & Custom maker since 2017, he produces work that draws on a wide range of inspirations — from Japanese Zen to his Colombian roots — bringing to life his own imaginings as well as collaborating with architects and interior designers on various projects. Aguirre Design’s furniture is characterized by a tactile contrast between materials: Steel, leather and high-quality wood meet to create an industrial aesthetic that places the emphasis on sensory experiences inspired by its building blocks.

Colombian-born Mauricio Aguirre, center, runs the New York–based Aguirre Design with his sons David and Mateo. Portrait by Asha Fuller

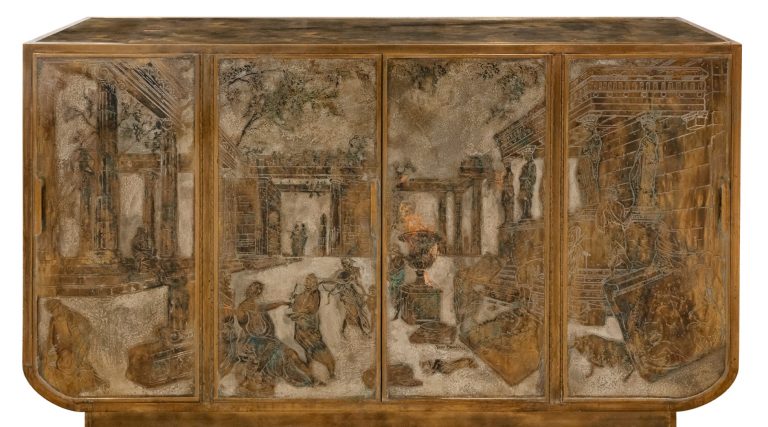

Aguirre was born in Bogotá, and in the mid-1980s, he launched three outposts of his boutique, A Estribor, there, plus one in Cartagena, which he curated with furnishings from local artisans. He recalls a formative visit to Bogotá’s El Museo del Oro that sparked a curiosity about the visual arts of the indigenous peoples of the Americas. Aguirre brought with him his affinity for the raw shapes he saw there when he moved to New York in 2000. “I try to adapt the simple, rustic shapes into something more contemporary, modern and thoughtful,” he says, pointing to his series of earthy cast-bronze objects. “The result is something that is very clean, with satisfying proportions.” Reflecting his attraction to shapes found in nature, one bronze bowl flaunts a sandblasted surface evoking the texture of wood grain; another is a contemporary reimagining of ancient ceramic stirrup spout vessels, named for their likeness to riding stirrups.

Today, Aguirre has been joined in his firm by his sons David and Mateo, who offer aesthetic input and oversee operations, although Aguirre’s vision guides the company. The trio conceive their pieces in a downtown Manhattan studio, then make them by hand in a Long Island City warehouse.

In an effort to support Project Lion, an initiative spearheaded by UNICEF USA to benefit displaced children in India, Aguirre Design recently collaborated with New York–based design firm Purvi Padia. The resulting work, the cast-brass footed Sinha bronze bowl, represents an intercontinental blending of styles, recalling pre-Columbian clay vessels but with a nod to brass elements borrowed from Indian design. Thirty percent of its sale proceeds go directly to Project Lion.

Shop Aguirre Design on 1stdibs

Alexandra Agudelo

Alexandra Agudelo finds strong similarities between her work as a silversmith and that of her former career as a dentist. Portrait by Juan Manuel Aguayo, courtesy of Cristina Grajales Gallery

“I believe my work lies in the conversation between the past and present,” says Bogotá-based artist Alexandra Agudelo. In her sunlight-drenched studio, surrounded by hammers, chisels and a curated selection of books, Agudelo transforms silver through the magic of fire, tenderly shaping the precious metal into delicately raw bowls, plates and decorative objects. She is fascinated by contemporary design and the metalwork of the native peoples of the Americas. In her craft, she transcends stereotypes of Latin American silversmithing, typically linked to Spanish influence, by playing with irregular textures, shapes and borders, perfectly executing each imperfection.

Before adopting metal as a medium, Agudelo discovered her penchant for design through an unusual avenue: She worked as a dentist for two years. “It is almost the same language,” she explains, noting that both crafts require a perfectionist’s attention to shapes and aesthetics. When she began experimenting with silver, she was taken by its dual nature: rigid when cool but, heated, quite malleable. “When I saw it transform from solid to liquid and then back to solid again in a matter of seconds, I was fascinated,” she says. “When I saw the colors the metal takes when it is melted and ready to be poured, I was hooked. In that light, it makes sense that metalworkers were considered the shamans of the tribes.”

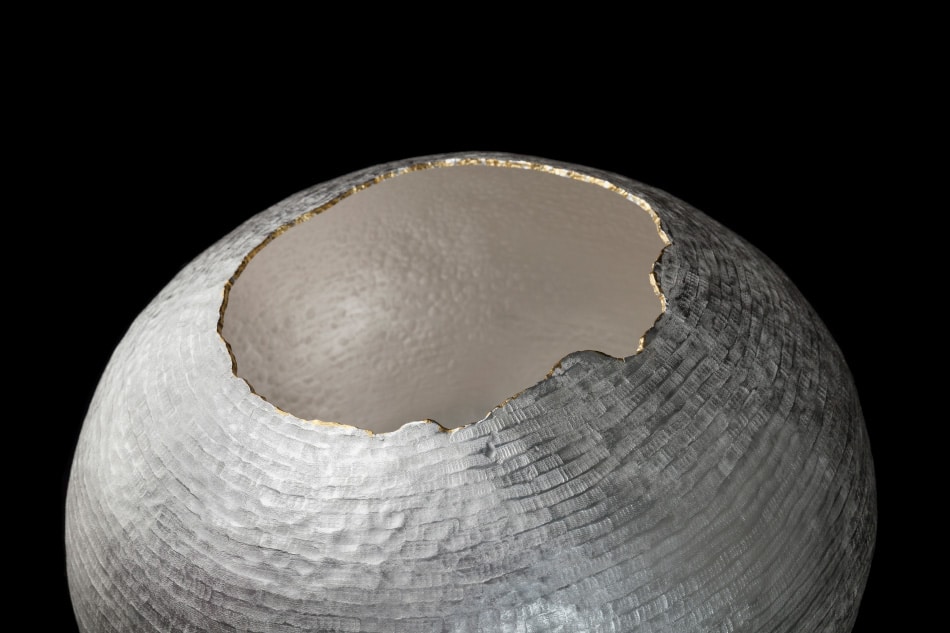

For an exhibition at New York’s Cristina Grajales Gallery (on now through June 8), Agudelo revisited the myth of El Dorado to create 20 silver works. Flecks of yellow line the rim of a vase, a basin’s golden interior shimmers inside a black shell — these details hint at the secret of the golden city, which inspired famed explorations by Spanish conquistadors. While some pieces appear light and delicate, others seem hard and severe. “My joy is to bring silver down from its pedestal and make it an accessible, everyday occurrence,” she says. “I found myself wrestling with the metal to make it reveal its secrets to me.”

Shop Alexandra Agudelo on 1stdibs