A recently released book on René Prou’s life and career has given new, and well-deserved, prominence to the influential designer. Here, he stands in front of one of the massive ocean liners he helped outfit, ca. 1930 (portrait courtesy of French Lines). Top: A gouache rendering of a design for a bedroom, ca. 1945 (photo by Philippe Fuzeau, courtesy of the Musées de la ville de Boulogne-Billancourt).

August 12, 2018As a child growing up in Paris, Patrick Frey heard very little about his illustrious grandfather, the Art Deco–era designer René Prou. Frey, the CEO of the Pierre Frey fabric company, was born in 1947, just three months before Prou’s death, and has no direct memory of him. It was only in later years that his mother, Geneviève, started relating her recollections of her father. “She said he was happy-go-lucky, enterprising and amusing,” Frey recounts. “He loved to entertain, organize fancy dress parties, and was full of projects.”

Prou was certainly prolific. A promotional brochure for his eponymous design firm stated that he had designed 60 private residences and 30 banks between 1918 and 1930, and his career continued another 17 years after that. He decorated some 500 train compartments — the most prestigious of which were for the Orient Express — and participated in the interior design of nine luxury ocean liners, including the Paris, the Île-de-France and the legendary Normandie. He was also extremely well connected. His friends included the Catalan painter Josep Maria Sert and fellow designer Louis Sognot; he collaborated on projects with Raymond Subes and Ivan da Silva Bruhns; and he went trout fishing in Normandy with Émile-Jacques Ruhlmann. “Prou was very, very well thought of in the period and was a very influential designer,” says Gary Calderwood, the founder of Philadelphia’s Calderwood Gallery, which specializes in French Art Deco and modernist furniture. “He did things that were every bit as good as Ruhlmann.”

Yet the decades since his death have not been kind to him. While Ruhlmann and other contemporaries like Pierre Chareau have been hailed as masters of 20th-century design, Prou has more or less fallen off the decorative-arts radar. Frey is hoping this will change with the recent publication of the first monograph devoted to him, René Prou: Between Art Deco and Modernism (Éditions Norma). Initiated by Frey, the book was overseen by his wife, Lorraine, and authored (with text in English as well as French) by Anne Bony, one of France’s leading design writers. It is an eye-opening and long overdue reevaluation.

Prou used modernist motifs in the lighting, rubber floor covering and wrought-iron banister on the ocean liner Colombie, 1931. Photo from Arts décoratifs à bord des paquebots, Éditions Fonmare, 1992

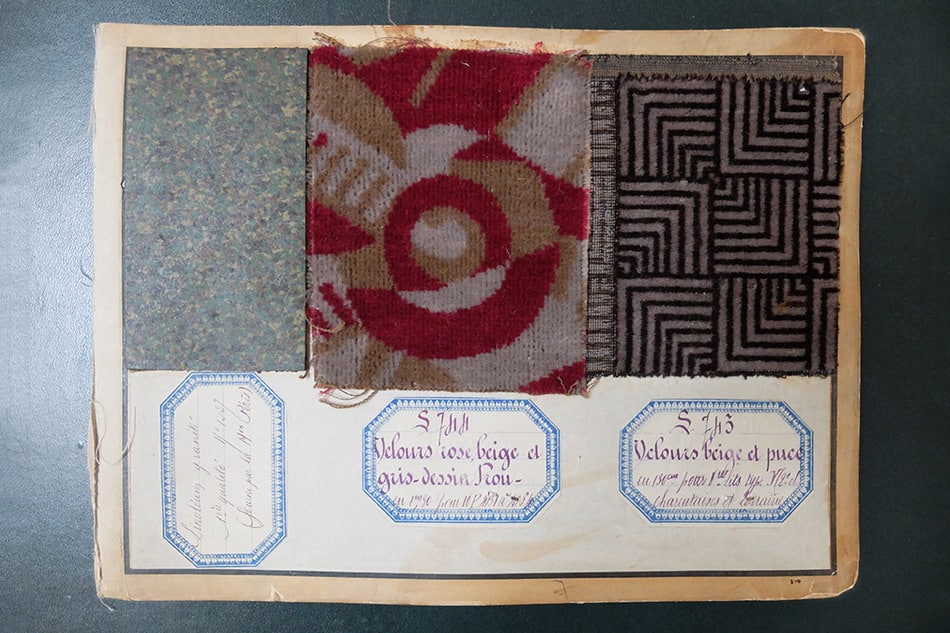

One of the challenges faced by Bony and art historian Gavriella Abekassis, who assisted with the research, was the lack of first-hand documentation. Prou’s son, Jean-René, ran his office for several years after his death, but after the business closed, most of the archives seem to have been destroyed or disappeared into thin air; Gary Calderwood is lucky to own 25 original Prou drawings. Bony had to rely almost exclusively on contemporaneous reviews, although the book also includes some nice personal mementos, such as a menu Prou illustrated in 1913 for Geneviève’s christening.

Ash burl panels and boldly printed upholstery enliven an Orient Express Pullman car. Photo by Jérôme Galland, courtesy of SNCF Médiathèque

Bony does an excellent job of providing context, including background on organizations that played an important role in the development of the French decorative arts in the early 20th century, such as the Salon des artistes décorateurs and the Union des artistes modernes. She doesn’t manage, however, to dig up much information about Prou’s background. Nothing is said about the professions of his parents, for instance. What we do learn is that he was born in Nantes on July 14, 1887, and later trained at an industrial-design school, the École Bernard-Palissy in Paris, between 1902 and 1908. He started his career working for the interior design firms Gouffé and Schmit & Cie. At the latter, he was responsible for the decoration of the Paris residence of the ambassador of Paraguay.

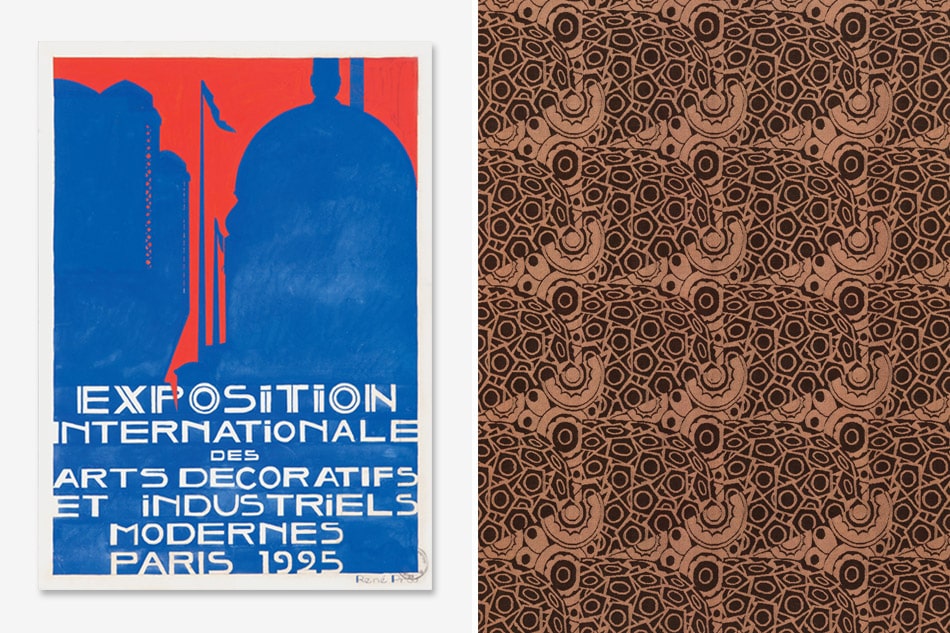

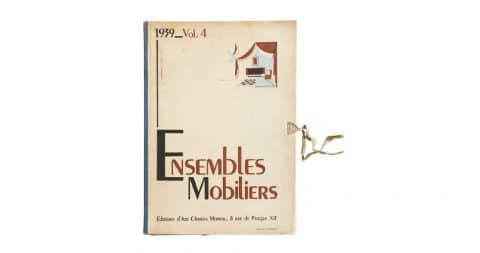

Prou began designing under his own name after World War I and never stopped. Among other projects, he imagined a women’s boudoir and a girl’s bedroom for the prestigious French Embassy pavilion at the 1925 Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes in Paris — widely considered the start of the Art Deco period. Prou created vases for the Manufacture de Sèvres, a fireplace for the living room of the Villa Noailles and a tearoom at the Lido cabaret on the Champs-Elysées. He also collaborated on the dining room of the Waldorf Astoria Hotel, in New York, and was commissioned to design a reading room, a VIP reception room and a 350-seat dining room for the Mitsukoshi department store, in Tokyo. The focal point of the latter was a luminous fountain at its center. He was a devoted pedagogue, too, teaching more than 3,000 pupils at the École nationale supérieure des Arts Décoratifs over two decades, among them Charlotte Perriand and the postwar modernist designers Pierre Guariche and Alain Richard.

Contemporaries praised “the purity and soberness of [Prou’s] lines,” Bony writes, and hailed him as “one of the uncontested masters of modern art.” The contemporaneous architect Eric Bagge stated: “There is scarcely among our decorators a man more in love with novelty.” Indeed, Prou’s output included sparks of innovation. He covered the floors of ocean liners with patchwork carpets made of linoleum, for example, and produced some strikingly modern-looking metal chairs. Yet much of his work was more traditional, regularly incorporating typical Art Deco geometric motifs and luxurious wood paneling.

This dichotomy was displayed in the interiors of his own homes. Prou’s wife, Andrée, had an aversion to the Art Deco style, and their Paris apartment was outfitted with classical 18th-century furniture, which he would regularly rearrange. “He sent his family to a hotel for as long as he needed to recompose everything,” Lorraine Frey says. Prou got his way in the south of France, however: In Antibes, he built a villa for his family called La Hubloterie (hublot is the French word for porthole, of which the house had three) and furnished the living room with a wonderful set of Bauhaus-inflected furniture made of red-lacquered Duralumin, an early aluminum alloy.

Sycamore armchair, ca. 1920. Photo courtesy of Sotheby’s/Art Digital Studio

Such aesthetic diversity might have been a key to Prou’s success during his lifetime, but it has not served him well posthumously. “The reason his work is not highly valued at present is because there is no identifiable Prou style,” notes decorative arts dealer Jean-Pierre Harter, of the Harter Galerie, in Nice. The most sought-after Prou pieces today are those in metal featuring scrolls and calligraphic lines. Still, a set of eight dining chairs in that style from the 1940s only made $2,000 when offered at Rago Arts and Auctions in New Jersey in 2017. And this past February, a pair of more modernistic folded-sheet metal chairs, circa 1928, failed to make their low estimate of $9,833 at Sotheby’s Paris, selling for just $7,682. According to Calderwood, few of the pieces attributed to Prou include documentation, a lack that poses another problem for his market.

Lorraine Frey hopes the new monograph will lead to a major reassessment. “I’d like to think people who have things by him will come forward,” she says. For her husband, meanwhile, the book has been a revelation — and something of a long-overdue gift. “At over seventy, I’ve finally discovered who Prou was,” he says with obvious enthusiasm. “That’s incredible, given he was my grandfather!”

PURCHASE THIS BOOK

or support your local bookstore