July 3, 2022Robert A.M. Stern’s new memoir, Between Memory and Invention: My Journey in Architecture (Monacelli), written with Leopoldo Villardi, is an engaging, frank and funny read — Stern tells you what he really thinks.

The architect, who founded his eponymous firm 50 years ago, recounts how, as a boy in Brooklyn, he always wanted to become a part of the glamorous Manhattan skyline he saw across the river.” (The stately co-op River House and the international-style buildings of the United Nations were icons of his youth.)

He did that and then some, helping to shape that skyline in profound ways, not least by turning himself into a leading historian of the local urban landscape. After earning degrees from Columbia College and the Yale School of Architecture — where he studied with legends like Vincent Scully, Paul Rudolph and Philip Johnson, and where he would later serve as dean — he launched his architecture career. In the beginning, he was a postmodernist of sorts, riffing on the shingle-style houses of the East End of Long Island.

Development: CBSK Ironstate

Later, he became one of the most important advocates for incorporating classical elements into contemporary design. His wide-ranging portfolio includes high-end residential work, exemplified by the 15 Central Park West luxury condo tower; college and university projects, including the transformation of the campus of Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government; cultural institutions, such as the George W. Bush Presidential Library and the Norman Rockwell Museum; and a fleet of office buildings, among them Philadelphia’s Comcast Center. He has also been involved in much civic master planning, perhaps most famously collaborating on the design for Celebration, Florida.

Stern, 83, spoke recently with Introspective about the new book, his long career and the things he covets and collects.

So, why did you write a memoir?

A young architect working in our office came to me with the idea of doing an oral history. But eventually, he moved on to other things, and I enlisted Leo. He is a very good researcher, and he uncovered things that I thought I’d forgotten or thought I’d never done. There comes a point where I think it’s an appropriate thing to do.

Are there any similarities between writing and designing a building?

Definitely. They’re both highly iterative processes. You draw a sketch, or you write a sketch, as it were, and then you go back and you redraw or rewrite.

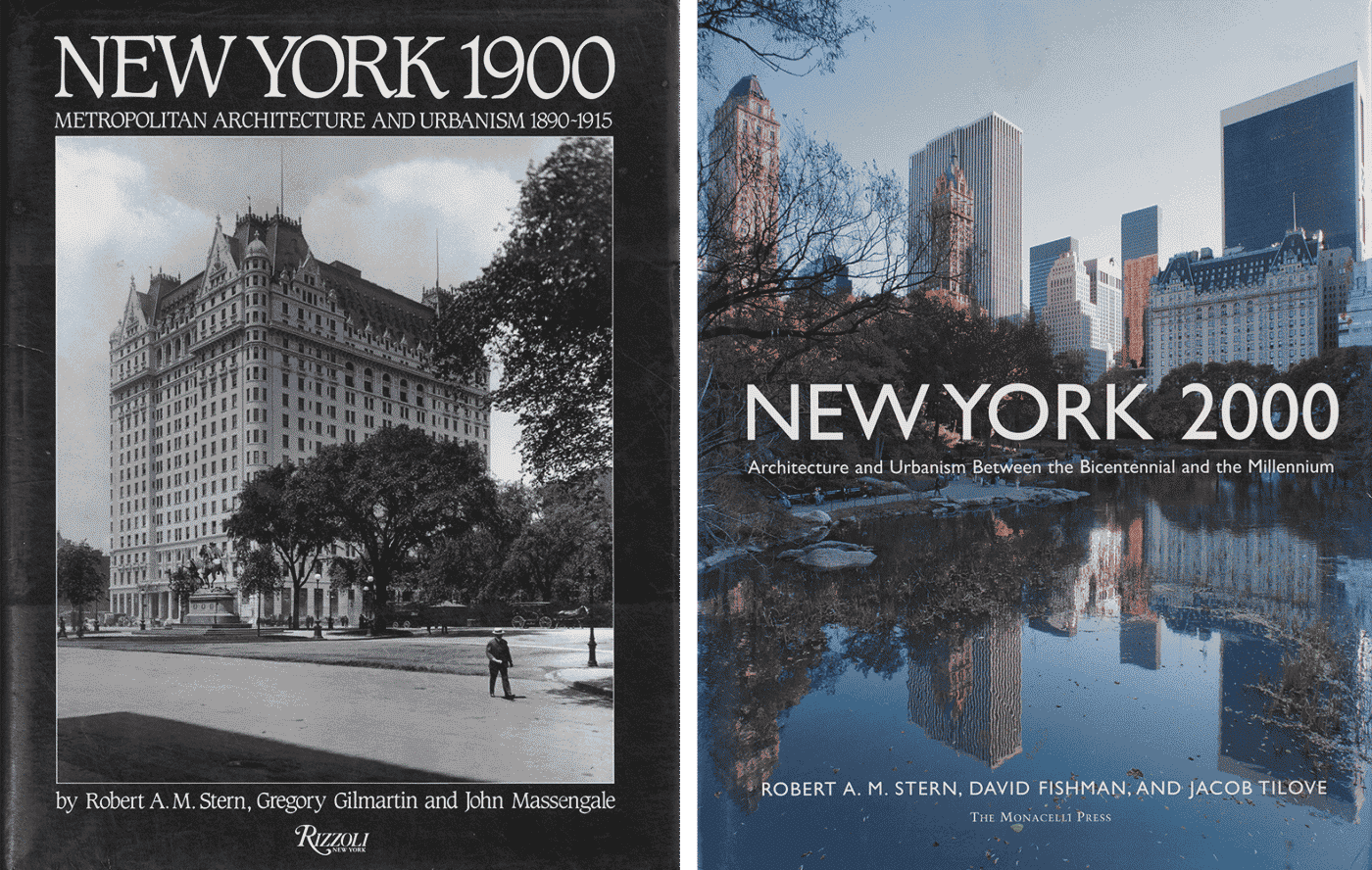

Your series of landmark historical books, also for Monacelli, surveying the urban architectural landscape, which began with New York 1900, has a new installment coming out next year. What can we expect from New York 2020?

When we finished New York 2000, my coauthors, David Fishman and Jake Tilove, and I agreed that we were finished with this series. But since the new century dawned, there have been so many transformative events in the city that we wanted to go on and record them. One gigantic surprise was the tremendous development activity in Brooklyn and Queens, but also in the Bronx and even Staten Island, the so-called forgotten borough. It’s a result of demographic change.

Your relationship with your mentor Philip Johnson had a big influence on you.

Philip Johnson consistently had his ear to the ground for trends, but he always had a sense of quality about his work and a discipline, which I admired. Philip and I always had great conversations. He would call me up to say, “Let’s have lunch,” which was usually at the corner table in the Grill Room of the Four Seasons.

How did you get to know him?

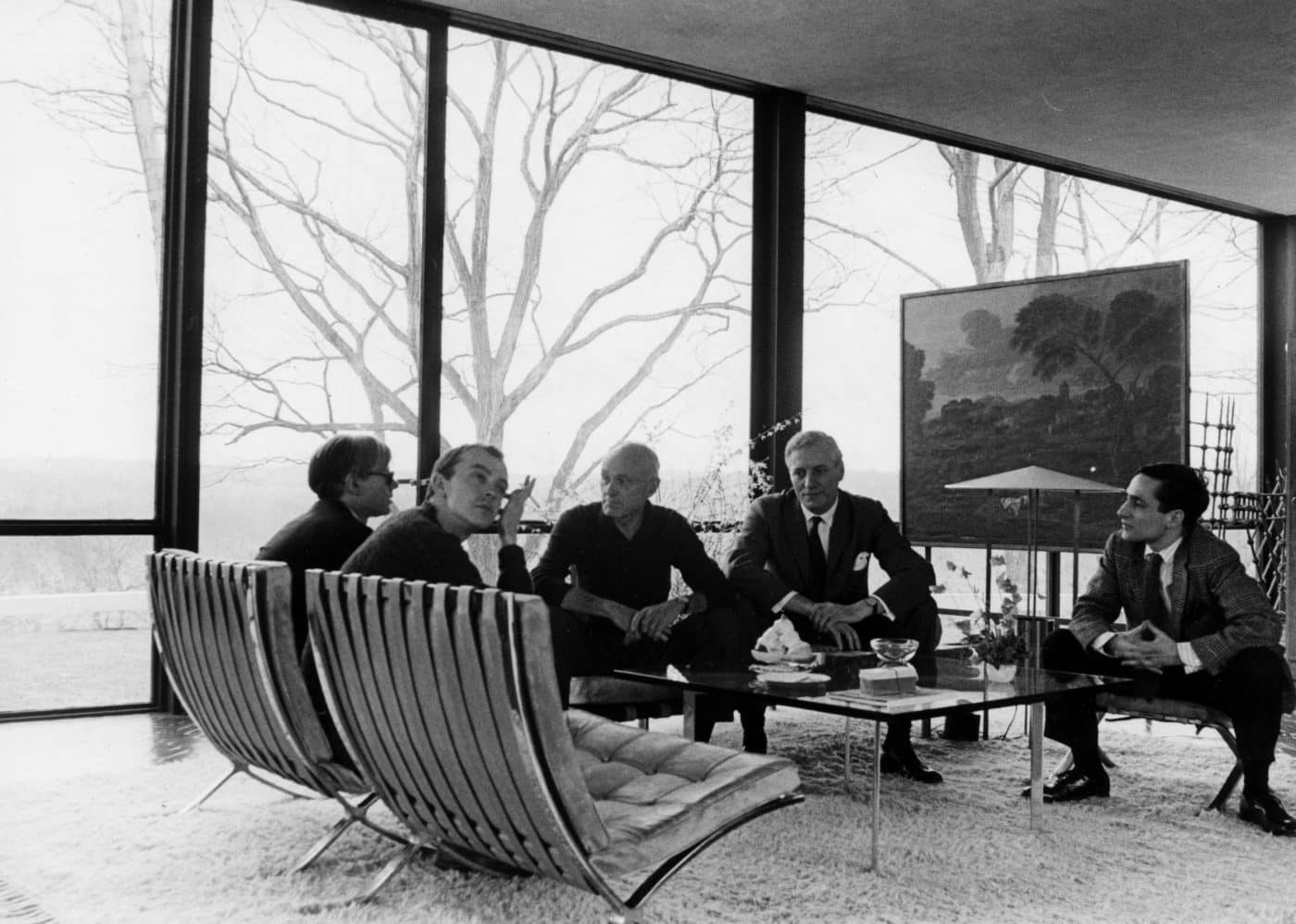

He and I had encountered each other, the first time being when I was in my first year at Yale architecture school. He’d come up for reviews. In any case, one of my classmates said, “Let’s see if we can go to the Glass House,” at that time the most famous residence in America.

So, the group suggested I call him. I don’t know why the students thought I was the guy, but I looked him up in the phone book — can you imagine someone as well-known as Philip Johnson had his phone number listed?

He said, “Sure, come up during the week when I’m not there. Pick a day.”

About seven of us went down. We had the run of the place and peeked around. It was a wonderful experience. Much later, he called me in the studio again, and he said he wanted me to have a new fellowship in the Architecture League in New York. It was the beginning of my career.

To me, your book illustrates that architecture, in fundamental ways, is a social profession — versus the Howard Roark solo-hero model from The Fountainhead.

I think that Ayn Rand really set the public perception of architecture in the wrong direction. Architecture is very social. The leading architects in history and certainly in modern history were all social animals. Philip Johnson was the personification of that. But it’s also social in that you work with clients. Most of the time you work with a developer or a public official. And then you work in teams of people as you create the designs for the building. And those teams consist initially of architects, but then you add on engineers. And then eventually, you add on other consultants, and on and on it goes.

Domestic design has been such a deep interest of yours, in particular the shingle style.

Vincent Scully wrote the book on the topic. When I got to Yale, there was the great Scully giving courses on Greek architecture and American architecture, in which the shingle style played a big part. And it all came into focus for me. Then I got to know Bob Venturi, who shared my affection for Scully’s work and for those houses. And I delved into them.

How did you delve?

My research was actually going around to look at those houses, going up to Newport and eventually settling as a summer resident in East Hampton, on Long Island, where there were many shingle houses. They were not particularly valued by people.

Then, I really dug in and wrote a little guidebook on East Hampton shingle houses. People would come to me and say, “Well, you know, I love the shingle houses, but I can’t imagine living in them.” They had all these small bedrooms sharing one bathroom.

So, I decided that I could design new houses, and clients egged me on to that — to use the shingle style with modern solutions.

One of the key phrases in the book is that you wanted “to put back into architecture what orthodox modernism had taken out.” What does that mean?

Orthodox modernism had taken out many things, one of which was ornament, which graces a building and gives it its individuality and helps the observer to connect visually. If you strip all of that away, architecture lacks, dare I say, personality.

But also, orthodox modernism was obsessed with machine production. Prefabrication was celebrated, and maybe it still is, as the be-all and end-all of architecture, not a means to realize different buildings.

You also say that architecture is part of a continuum.

I believe you should go backwards to go forwards, just like in music or painting. An artist like Frank Stella will talk about the work of baroque painters and their influence. And sometimes it’s a little hard to see that in Frank’s work, but his heart’s in the right place.

Fifteen Central Park West is such an influential building. Why do you think that is?

It’s such a prominent site. Our clients, the Zeckendorf brothers, encouraged us to use stone in a richly detailed way. The idea was that the tower on top of the building would have an interesting silhouette so the building could be big but not just a blockbuster. That’s why people like it. It reminds them visually of buildings they admired, particularly from the glorious skyscraper period of the nineteen twenties and early thirties in Manhattan.

My own early experiences in architecture came from renovating grand old apartments on Central Park West and on the Upper East Side. I saw that these had great bones, but again, the issue was to adapt them to contemporary life without destroying the good things about them. So, I tried to give 15 Central Park West the characteristics of apartments that I had admired and tinkered with.

You had an eighteen-year tenure as dean of the Yale School of Architecture. What were your achievements?

I think I brought a new vitality to the school. It had gotten a bit sleepy. We introduced hand drawing as a core consideration in the program. The most important thing: We revived Yale’s tradition of having diverse points of view in the studios, not a closed set of orthodoxies. I think I put Yale back on the map. And I’m told it remains on the map under Deborah Berke, my successor, who’s doing a very good job.

Are there younger architects you admire?

Someone like Gregg Pasquarelli, at SHoP Architects, does very interesting buildings, Bjarke Ingels too. But there are also younger architects, like Mark Foster Gage, who was a student of mine, worked for me, trained originally as a classicist but is now an extremely inventive modernist teaching at Yale. I watch carefully what he’s doing.

The profession has changed a lot.

In the past, it was pretty much a white boy’s profession. This has changed for the better, and it’s continually evolving. I do my best to support the efforts of minority candidates for admission to top schools and to get jobs in the best offices and to really be able to show their talents.

Do you live with design in terms of furniture and objects?

I’m not a collector by instinct, but I am sitting on a sofa I designed in a room I designed that also includes some bentwood furniture from the late nineteenth century. Once I buy something, I tend to keep it forever. I have a small house on Long Island in East Hampton that reflects my interest not only in shingle-style architecture but in furnishings.

I have bought things from the lexicon of contemporary modernist furniture — Gio Ponti Superleggera chairs in my study and Le Corbusier swivel chairs in the office.

In the eighties, I also collected architectural drawings when Max Protetch had his gallery, ranging from Gunnar Asplund works to those by Eliel Saarinen to Léon Krier. So I’m eclectic.

I am told that you owned, and then sold, Donald Judd’s Untitled (DSS 42), from 1963.

Philip Johnson’s companion, David Whitney, became my art adviser. And David came to me one day saying, “Donald has a very early piece” — and this was in the early sixties — “and he has no room to store it, and he wants to sell it. Would you buy it?” And I said, “Sure. I would be delighted.” And it was quite expensive for those days, $2,500.

It subsequently proved to be one of Donald Judd’s seminal pieces. And a few years ago, its value was so great and its insurance so costly, I put it up for auction and it did very well [fetching $14.2 million at Christie’s], and I used that money to establish a fund in support of architectural culture at Columbia College and Yale School of Architecture.

What’s the future direction for the firm that bears your name?

I hope it will go forward in its diversity, in its willingness to take risks on new artistic ideas, but remain true to the basic core values of a sense of history, a sense of research as the basis of design, a sense of architecture that isn’t out to knock your socks off but to fit in. Meanwhile, I’m still there.

Are there other architectural memoirs worth reading?

I would say Frank Lloyd Wright’s autobiography is an amazing document. He wrote it at the bottom of his influence and career, as a part of an effort to reinvent himself. Of course, he made up a great deal of it. And that’s the fun of it, in a way.

I’m not going to tell you how much I made up in my book. That may come out after I’ve gone to my reward.