July 23, 2023“PLEASE DON’T TOUCH THAT!” I hear myself saying, too sharp, too fast.

I give tours at Manitoga/The Russel Wright Design Center, mid-century industrial designer Russel Wright’s home, studio and 75-acre property in Garrison, New York, about an hour north of New York City. We site educators are an eclectic group of Hudson River Valley locals. I live in nearby Beacon, and my background is in the theater, but our gang includes design, art and nature lovers of all kinds drawn to the house and the beauty of its surroundings.

Wright’s modernist home, completed in 1961, is built into the cliffside of an old quarry pit, which Wright turned into his family’s own private swimming pool by diverting a stream and sending it down seven layers of huge granite slabs he’d arranged to create a picturesque waterfall.

In the warmer months, the house and studio are accessible through a short woodland hike, by guided tour only. The rest of the paths on the property are open to the public, free of charge, all year long, as Wright intended. The site is a National Historic Landmark, both for its landscape and its architecture. Stewarded by the nonprofit that restored the home and revitalized the grounds with breathtaking fields, flowering shrubs and carpets of moss in the early 2000s, it began welcoming visitors in 2010.

At this moment, my wonderful tour guest (maybe my favorite guest today), his curiosity piqued by the bits of knowledge I have strategically planted, has seen the Hans Wegner valet chair next to the shelf that Wright custom built to divide the sleeping area from the desk area in his private studio. Like an octopus who thinks with its arms, my inquisitive visitor has reached out to see if the seat actually lifts up.

He recoils at my admonition.

Oh, dear. Success and failure, all at once. If I’m doing my job right, by this point in the tour, my guests should have that sense of childlike wonder, entranced by the idyllic natural setting and immersed in a world of creative possibilities. Who wouldn’t be fascinated by a ceiling made from pine needles and epoxy? Who wouldn’t want to push on a door that looks as if it’s part of the wall? Who wouldn’t want to test out all the furniture? This place is a Willy Wonka’s chocolate factory of temptation for the design minded.

Wright’s claim to fame was as a designer of dinnerware and home furnishings, and his name recognition was due in large part to the savvy of his wife and business partner, Mary. “Good design is for everyone” was their motto. Together, they wrote and published Guide to Easier Living in 1950, advocating for a new, casual, elegant America where men do the dishes and other household chores (Italian designer Massimo Vignelli wrote the introduction for the reedition in 2003).

The couple’s American Modern dinnerware line for Steubenville Pottery was (and still is) the best-selling in U.S. history, with more than 200 million pieces sold during its initial two-decade-long production run in the 1940s and ’50s. As Martha Stewart put it, “The Wrights were the leading proponents of what is now known as all-American modernism.” (Stewart’s favorite dinnerware, by the way, is the American Modern Granite Gray.) In 2021, the Russel & Mary Wright Design Gallery, showcasing some 200 examples of their work, opened in a section of the main house.

Russel Wright also created furniture for makers like Heywood-Wakefield, Statton and Old Hickory. Perhaps his best-known designs were the streamlined maple tables, chairs and case pieces he conceived for Conant Ball starting in the 1930s (Mary, the marketing whiz, coined the term blond wood to describe them).

But those near and dear to Manitoga see the property itself as Wright’s ultimate artistic triumph.

He and his wife purchased the plot, a former granite quarry and logging site with a small farmhouse, in 1942 as a summer getaway from their home in New York City. Although Mary died in 1952, Wright was determined to build a modern house on the property for himself and his young daughter, Ann. He enlisted architect David L. Leavitt to execute his plan, in large part because of their shared admiration for Japanese design concepts. Ann thought the shape of the rough quarry wall looked like a dragon curling around the pit to drink from the pool, so Wright affectionately dubbed the cliff and its dwelling Dragon Rock.

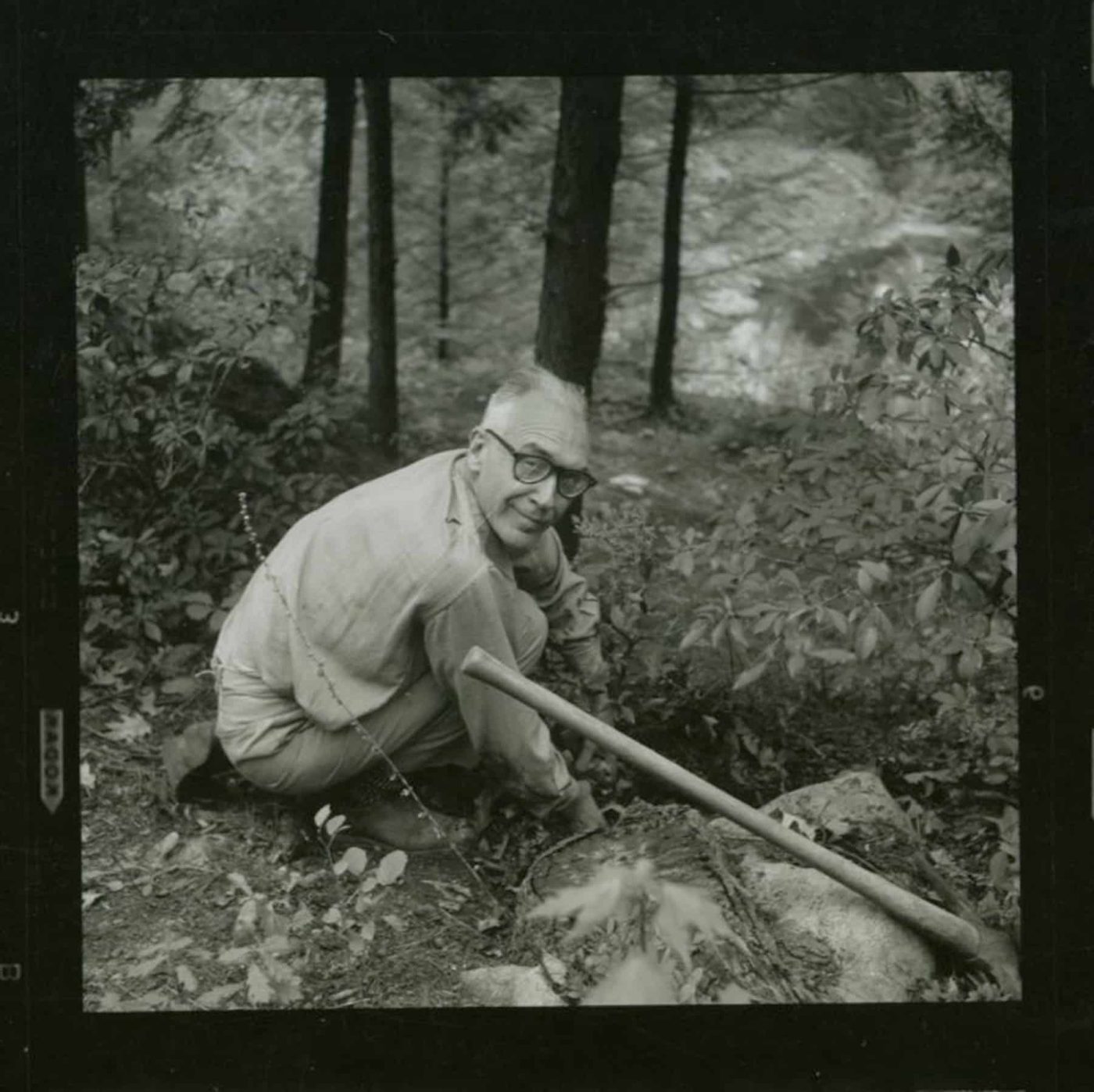

Personally, I’m compelled by trying to figure this man out. Although an advocate for a modern, industrialized way of life, he spent all his free time creating paths through the woods. He found his way to his vocation as an industrial designer through the theater, training as a scenic designer with the likes of Norman Bel Geddes, so he was not a stranger to world building or storytelling. The name Manitoga is derived from Algonquin words meaning “place of great spirit.” Despite being a pioneer in mass production, he spent years learning the landscape, designing in harmony with nature and building a singular, irreplicable home. It is his own private decades-long experiment in how to live.

When leading tours, I sometimes cheat and, instead of holding forth, try to coax information from my guests. “Are there any collectors in the group who can tell me who created this table?” I ask, gesturing to the Eero Saarinen Pedestal table in Wright’s dining area. It’s placed at the foot of a two-story window so that those seated around it are under the canopy of trees, eye level with the middle of the waterfall.

Even the shyest design nerds can’t help but out themselves by slowly cocking their heads to the side and squinting to see the base of the table, because something is off. It’s just one example of how Wright customized the designs of his contemporaries for his unusual home, in this case flipping the base so that the narrower end is at the bottom and boring it right into the uneven granite floor.

Collectors might gasp and clutch their pearls at this borrowing and tweaking, at the lack of reverence for authorship, but I imagine it was a form of flattery. It transports us back to a time when industrial design was an experimental movement, a set of changing ideals rather than an established marketplace. A village throwing ideas around and riffing.

Manitoga’s tours run from May into November. I started in May 2022, so I have now seen the property over the course of an entire year, and each season has its own woodland garden highlights. In the spring, the path to the house winds through pink and white mountain laurel flowers. In the summer, a spectacular orange wall of daylilies blooms on the old quarry’s granite cliff.

I even got to experience the site during the winter, with no one else around. During those moments of stillness, I gave myself permission to sit, gingerly, in Wright’s Reading and Writing chair, complete with hinged side tables, where he sat and wrote about the possibilities of a new, modern America. He placed it on the mezzanine, overlooking the sunken living room and the panoramic vista of the quarry pool path and the hemlock trees. I’m sitting in it now, imagining the past.