May 7, 2023The collaboration between a designer and the photographer tasked with documenting her projects is an intimate one. If they are lucky enough to bring out in each other heightened levels of trust and appreciation, the relationship intensifies and evolves over time — and across varied projects.

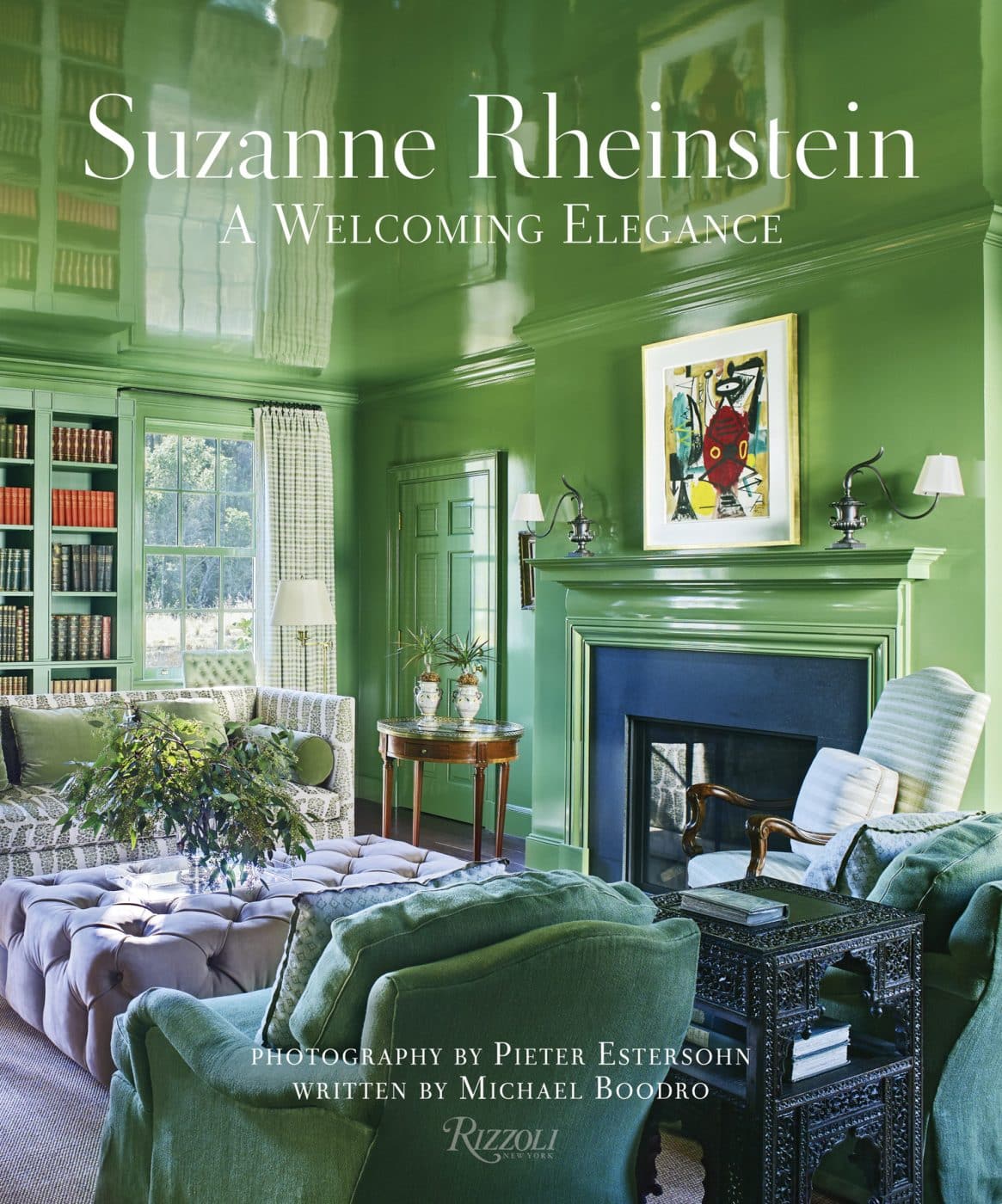

I was fortunate to have experienced this type of relationship with Suzanne Rheinstein, the Los Angeles decorating legend with whom I worked on countless magazine features and three books, including Suzanne Rheinstein: A Welcoming Elegance (Rizzoli), published in March just days before Suzanne’s death from cancer at the age of 77.

Collaborating with Suzanne meant enjoying the privilege of traveling with her from project to project — and having my face hurt at the end of each day because we always laughed so hard and had so much fun. We also would indulge each other’s curiosity.

I tend to ask a lot of questions when I’m working, often so that I can understand what needs to be prioritized in an image and how the narrative of the story might best flow. When an architect or designer responds that something “just looks right” or “feels like the right choice,” my antennae go up immediately, and I wonder if they’ve done their homework. (Yes, I get “judgy,” as my son, Elio, says.)

Never once did this happen while working with Suzanne. Every single component in her interiors was there for a reason that she could explain with erudition, nuance and clarity. Of course, everything felt like it belonged where it was, but the distinction with Suzanne’s work was that she had studied, read and, perhaps most importantly, traveled all over the world to both satisfy her inquisitive nature and inform her design choices.

If you are going to reference the work of Renzo Mongiardino, as Suzanne did in a guest house in West Hollywood, it helps to have done more than just look through old shelter magazines featuring Mongiardino projects. Suzanne believed it was crucial to see your inspiration in person in order to dial it up or make it your own. Tucked away on a compound in Los Angeles, a family gym was built in homage to the Gustavian-era metal tent at Haga Park, in Sweden. The gym’s success owes to its proportion and scale, which Suzanne picked up during her visit to Stockholm.

The gardens and landscapes surrounding the houses she worked on were enormously important to her, and travel and research informed her work outdoors, too. (The Garden Conservancy, which she long supported with passion and commitment, honored her this past winter at a gala at the Union Club in New York City, where I was thrilled to be her date.) I’m not sure she would have taken on a client who didn’t share her appreciation for gardens.

Suzanne’s work has been labeled “traditional,” but it was actually much more ambitious and modern than first impressions might suggest, so rooted is it in her own personality and in showcasing the interests and collections of her clients. Her approach might at times be thought of as “scholarly,” but this isn’t really accurate either, since that implies a somewhat labored process and Suzanne’s creativity flowed freely and organically as an expression of her identity.

We geeked out on the stories behind things. As we worked, we’d talk about the Palazzina Cinese, in Palermo; Fortuny fabric (antique versus modern); and why using Georg Jensen silver really matters. We’d stop shooting when the sun went behind a cloud, and she’d share her thoughts, for example, on why a grouping of black ceramic vessels by Kaori Tatebayashi fit perfectly in front of a Lucio Fontana painting. She was correct, of course; it was a magical and unexpected juxtaposition.

Indeed, I’d always come to see the “magic” after she explained her process and how her eye worked — which she did because she wanted to share her joy and appreciation for these things, not to dominate or show off. Curiosity, which again, Suzanne had in spades and for which I so loved and admired her, is a humbling force.

Suzanne was also passionate about repurposing objects and furniture from her clients’ previous homes, a “green” practice that feels correct for these times. For Suzanne, it went deeper than correctness. Although many of her clients could easily afford to scrap their previous possessions and start anew, Suzanne promoted the ideas of connecting not just with the past but with their personal histories as well. She cherished the process of dovetailing old possessions into a new home and a new design ethos that reflected the environment her clients wanted for that period of their lives.

While shooting A Welcoming Elegance with Suzanne, I often felt I was having a reunion with old friends when I recognized pieces I’d previously documented in earlier residences, be it a 15th-century Spanish chest on a stand or a collection of 18th-century embroideries by women.

I mention the fact that these were by women because this is how Suzanne introduced them to me — the person who’d created an object was paramount for her. The ceramic garniture in the entry of a Bel Air house, she’d tell me, was made by Eve Kaplan, and the collage over the mantel in the Newport Beach, California, project was by Marian McEvoy. Suzanne was intent on always crediting her collaborators, because she understood the deeply cooperative nature of her work.

The apotheosis of her career, I believe, is her own last home in Montecito, which she designed with James Shearron and Richard Bories and which figures prominently in the book. Here, in an almost reductive mode, her true genius manifested. (I told her while we were shooting it that it seemed she had really put on her big-boy pants for this project, and she howled with laughter.) It is a rare talent who can design a home with such a decisive hand.

I hope I was able to capture the degree of thought that went into this home, which she designed as a retreat during a period of profound health concerns. While we were shooting, often in the afternoon, Suzanne would let me know that she was just going to lie down for a moment. I knew she was experiencing significant discomfort from the challenges of confronting cancer, and the quiet nobility of these announcements made me love her even more.

There was an undertone of not wanting to disturb my thought and work processes, the desire to support the esprit de corps of the team and the confidence of not needing to be the superstar. Suzanne was, after all, someone who admired the subtle and whispering qualities of the back of the fabric. Hail!

Purchase the Book