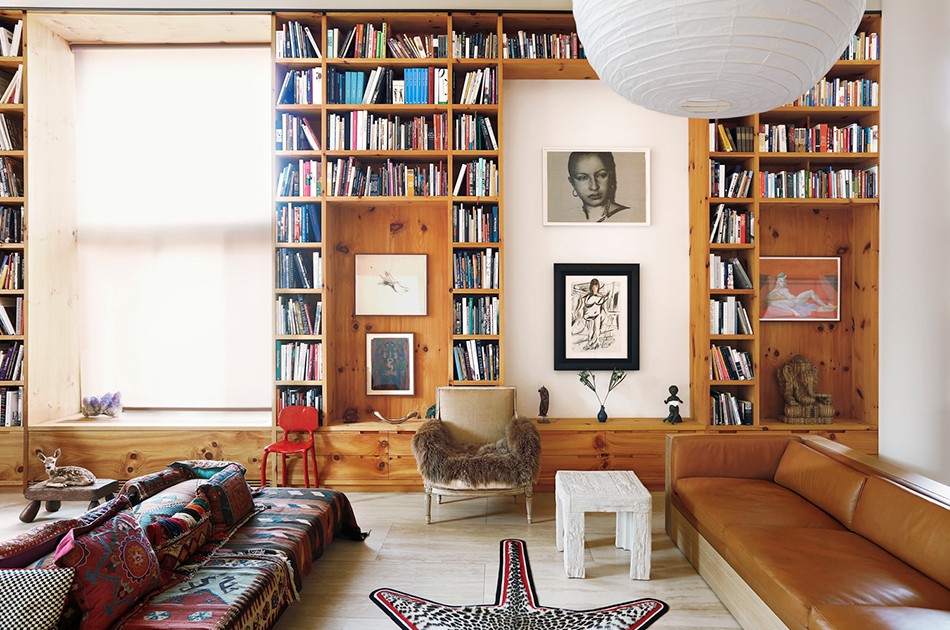

March 23, 2015Architect Kevin Lindores (left) and interior designer Daniel Sachs created a loft on New York’s Bowery (top) for Inez Van Lamsweerde and Vinoodh Matadin, incorporating the Dutch-born photographers’ own images into their home, as well as those of other artists and a chair by Maarten Baas. Portrait by Jeffrey Blocksidge, top photo by Inez and Vinoodh

It was Frank Gehry who initially brought interior designer Daniel Sachs and architect Kevin Lindores together. The two met in 1987 while they were employed by Gehry — but they had been sharing a passionate interest in his work long before that. As a child, Sachs had taken to clipping photos of the starchitect’s work out of magazines. Lindores, meanwhile, had been struck by a Gehry talk he’d attended as an architecture student at Carlton University, in Ottawa. “It was one of those eye-opening experiences,” he recalls. “I realized architecture didn’t have to be International Style glass towers or postmodern cartoons. It could be whimsical and fun, but serious at the same time.” There was an almost immediate professional understanding between Sachs and Lindores, too. As Sachs tells it, “Kevin was one of the few people who could second-guess my way of resolving problems.”

Such a communion has been a key element of their long-lasting success (and no doubt of their relationship — the two are partners in life as well as work). Today they live together in Manhattan’s West Village in a former artist’s studio that dates back to the 1920s, and they run their eponymous firm — Sachs Lindores Architecture, Interiors — from a space on the top floor of a brick warehouse in Williamsburg, Brooklyn. Their employees number seven, and their clients include the likes of artist Philip Taaffe, poet Tom Healy and Dutch-born photographers Inez Van Lamsweerde and Vinoodh Matadin.

For real-estate magnate Steve Guttman and his wife, Kathy, who live with an impressive art collection, the firm designed a Miami loft incorporating a Polaire sofa by Jean Royère, a wood bowl by Alexandre Noll and a coffee table by Jean Prouvé. Photo courtesy of Sachs Lindores

In many ways, Sachs and Lindores are perfectly complementary. “Daniel has an amazing eye for color, texture, scale and proportion,” notes another client, art collector and philanthropist Kathy Guttman. “Kevin is the master of space.” That said, there is a significant amount of overlap. “Right from the start, when we work on the architecture, we’re already talking about what the furniture is going to be in the rooms, the fabrics and colors, the finishes,” says Lindores. “I think that’s one of our real strengths — that we’re both heavily involved in all aspects of a project.”

Born in Toronto in 1965, Lindores claims that his love of buildings likely derives from his maternal grandfather, who built houses as a job on the side. “He was constantly working on projects — constructing or renovating a building,” Lindores explains. Sachs, meanwhile, was born in 1955 in Virginia and raised in San Francisco, where his father owned a high-end women’s department store called Ransahoffs. (Jimmy Stewart memorably shops for Kim Novak there in Hitchcock’s Vertigo.) Sachs enrolled at UC Berkeley intending to study architecture, but he quickly found himself more interested in sculpture — and he soon transferred to the Cooper Union in New York, where Taaffe was one of his classmates. After graduation, Sachs and two friends set up a company called Curzon Studios, which famously made frames for Robert Mapplethorpe and a dining room suite commissioned by avant-garde theater director Robert Wilson for the New York apartment of art collector Paul Walter, among other projects. In 1982, Sachs moved to Los Angeles, where he spent much of the next decade making furniture and sculpture in Gehry’s studio. In 1993, he moved back to New York to found an interior design practice, called Snook, with Uruguay-born designer Fernando Santangelo. It was wildly successful: within just a few months, Bette Midler commissioned them to decorate her Manhattan penthouse (which was only recently featured on the cover of Architectural Digest).

“Right from the start, when we work on the architecture, we’re already talking about what the furniture is going to be in the rooms, the fabrics and colors, the finishes.”

In the kitchen of the Guttmans’ Manhattan home, an Alvar Aalto light fixture lights up a table and banquette of Sachs Lindores’s own design; the chairs are Finnish antiques from around the 1940s. Photo by Stephan Barker, courtesy of Sachs Lindores

While Sachs was making waves in New York, Lindores had left Gehry’s studio and returned to his native Canada to finish his architectural training — but they kept in touch during this time. Finally, in 2000, the two men joined forces personally and professionally, and created their own firm in New York.

Today, their collaborations are marked by a compelling sense of balance across all elements and a seamless integration of influences that might appear disparate in less-seasoned hands. “Our rooms are never murky or unfocused,” insists Sachs. “They have a well-defined architectural approach. And we try to make things livable and comfortable, even when they have a formality to them.”

That said, both Sachs and Lindores have difficulty pinning down their specific style. “I love all kinds of beautiful buildings, from crazy mud huts to the château at Versailles,” explains Sachs, while Lindores confesses to an interest in “many different genres.” Ask him for his influences and he mentions not only Viennese modernist Adolf Loos, but also 18th-century German baroque architect Balthasar Neumann. Sachs also shares his great passion for the past. “I’ve always loved the patina of objects,” he admits. “I love the way it feels when you walk across a creaky floor — that age and wear. Those things can somehow be very edifying.”

Their projects to date have certainly been varied. They include a duplex in an 1830s Manhattan townhouse, which features stately columns, an 18th-century English mantelpiece and a stellar collection of 20th-century furniture by the likes of Jean Royère, Vladimir Kagan and Pierre Chareau. They have also constructed a ground-up shingle-style house in Portsmouth, Rhode Island, influenced by the work of McKim, Mead & White, and have worked on a 3,400-square-foot loft on the Lower East Side for Van Lamsweerde and Matadin, collaborating with Simrel Achenbach of the Brooklyn-based Descience Laboratories. The slightly eccentric brief they were given for that interior called for a cross between a Japanese tea house and a Swedish sauna. “We wanted the place to ideally look like we’d been living there since the nineteen-seventies,” declares Van Lamsweerde.

In the apartment of writer David Hay, on New York City’s Fifth Avenue, the art in the dining room is by Thomas Ruff, while the Camel table is Richard Neutra, the chairs Jens Risom for Knoll and the hanging light fixture Anton Fogh Holm and Alfred. J. Andersen. Photo by Jeffrey Blocksidge, courtesy of Sachs Lindores

To date, Sachs has worked on a total of seven different projects for poet Healy, ranging from a Miami apartment in 1998 to a Tribeca loft last year. Healy praises both the “understated elegance” of the designer’s style and “the calm, gracefulness of his taste,” going on to say, “I marvel at Daniel’s understanding of color and pattern, how and why some things work together and some don’t.” Another firm fan is artist Taaffe, for whom Sachs and Lindores are currently designing a studio residence building by the Housatonic River, near Cornwall, Connecticut. “There’s an elasticity and a fluidity to their work, as well as a deep understanding of our historical situation,” Taaffe enthuses. “It’s an architecture without egotism. Their sensitivity is very unique.”

All things considered, the duo’s work has little in common with that of the man who facilitated their fated meeting, years ago. “After seeing the bravura of some of Gehry’s buildings that jump out at you, it became interesting to me how you make things that can both be subtle and still have a kind of strength to them without screaming out that they exist,” Sachs reflects.

Their career path has been similar in spirit. “Kevin and Daniel could have a giant design firm and work only for gazillionaires,” Healy notes. “But they chose to keep things small and special. They’re best with clients who can slow down and be as attentive to detail as they are.”