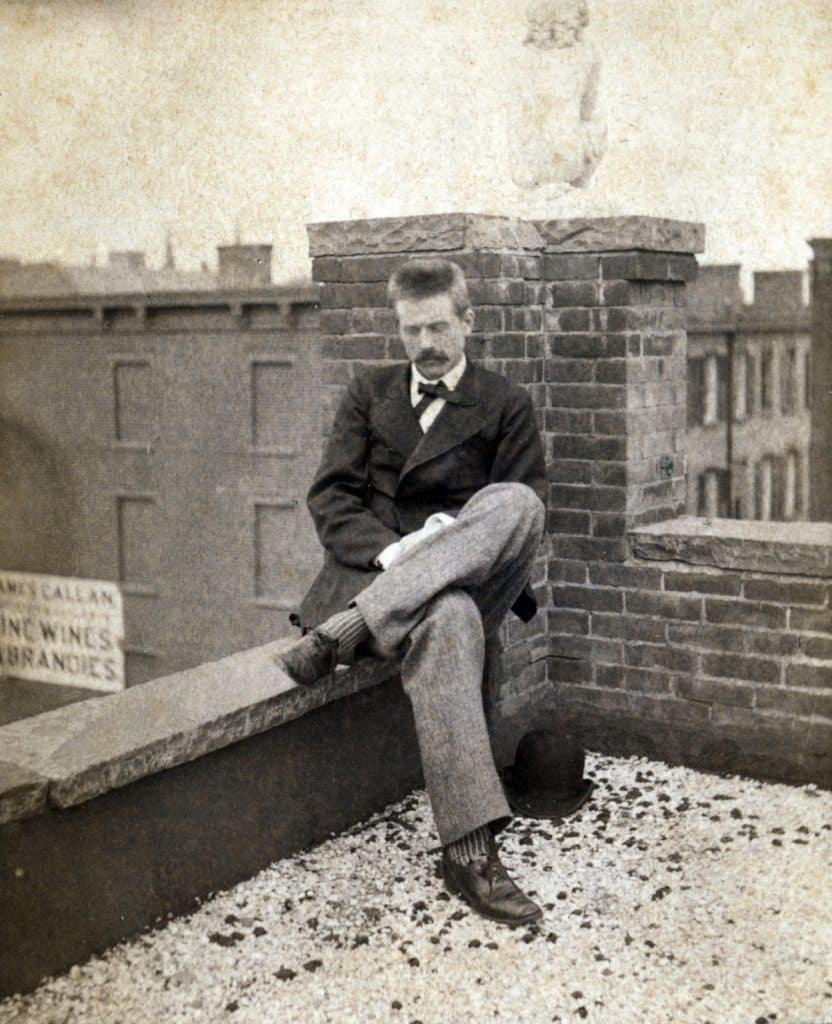

January 3, 2021By the time he died, in 1906, the great American architect Stanford White was well-known for his public buildings in New York and other East Coast cities. But the McKim, Mead & White partner also designed more than 100 residences, including some of the great shingle-style mansions of Long Island and New England and structures whose classical forms are reminiscent of his civic architecture.

“He loved houses, and he kept doing houses all his life,” says Samuel White, Stanford’s great-grandson and an author and architect in his own right. Charles McKim was busy with institutional projects, Samuel says, and William Mead wasn’t interested in residential work. That left the townhouses and country estates to his great-grandfather, whom the New York Times once described as the firm’s “impulsive creative genius, always in a hurry but completely assured in his ideas.”

Many of White’s houses remain standing, and more than a few are open to the public, including a Washington, D.C., mansion that is now a residential hotel, a Manhattan townhouse that became a French cultural center and several Newport showplaces that offer tours.

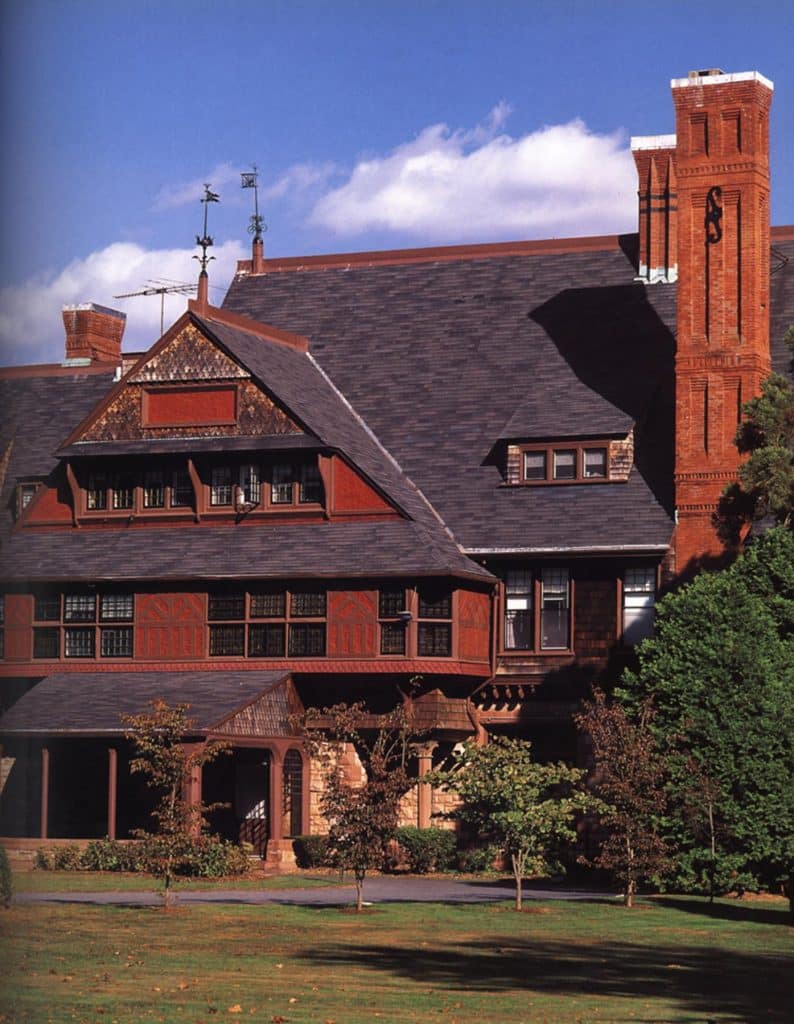

One house not open to the public is Stanford’s own weekend residence, Box Hill, in Saint James, on the north shore of Long Island. Its owner is Samuel’s brother Daniel White, who bought it from their parents and has been restoring it for more than 20 years. “Luckily, he has access to free architectural services,” jokes Samuel, referring to the role he has played in the restoration. Problems include a roof that leaks — Stanford alternated large and small dormers for effect, creating “the most complicated roof I’ve ever seen,” says Samuel — and a 125-year-old kitchen.

When he isn’t helping his brother or working at his longtime firm, PBDW Architects (formerly Platt Byard Dovell White), Samuel often writes about his famous forebear — one of whose structures, the Players Club on Gramercy Park South, he can see from his own Manhattan apartment. (He can easily walk to three others: the Washington Square Arch, the Century Association and the Judson Memorial Church.)

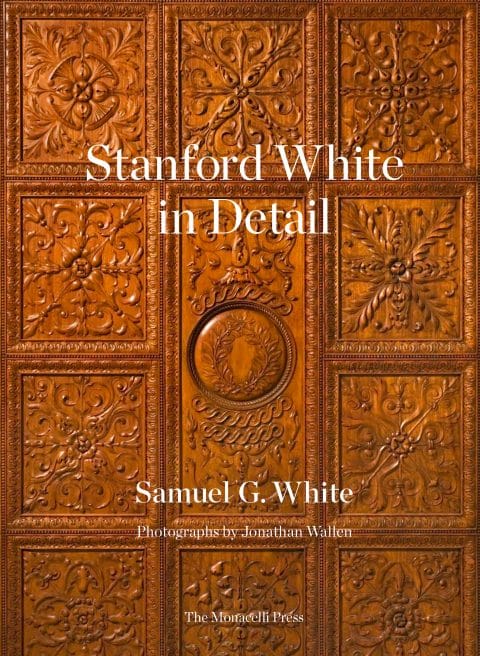

Samuel’s fourth volume on the subject is Stanford White in Detail (Monacelli), edited by his wife, Elizabeth White, with photos by Jonathan Wallen. “This book turns the telescope around. Rather than focusing on the houses, it focuses on the details that make the houses so wonderful,” he says by phone from the front porch of Box Hill. “It’s a very amiable subject.”

He proves that here, as he takes Introspective on a tour.

BOX HILL

This was originally a farmhouse “with no architectural ambitions,” Samuel says. Stanford enlarged it several times after his wife received a large inheritance, around 1884. In 1903, he covered the entire building in “pebble dash” (rocks pressed into mortar). “The house is right near the Long Island Sound, and there are wonderful beach pebbles that really capture the light,” says Samuel. The windows are framed in larger pebbles. “It’s all about texture.”

When it came to the interiors, Stanford was a compulsive purchaser whose “appetite for beauty respected no borders,” Samuel writes. “He collected temple ornaments from Japan, carpets from Turkey, tiles from Holland and mashrabiya screens from Morocco.” Then, he filled rooms with as many pieces as could fit. “At Box Hill, the density of decorative arts was much greater when he was alive,” says Samuel. In recent years, “my father sold pieces to pay our college tuitions, and then my brothers and sisters and I took things.” (Samuel is one of 11 siblings.) As a result, he jokes, “what you see today is the Mies van der Rohe version of these rooms.”

Stanford often bought fragments of genuine antiques and had them “restored” by local stone carvers; an example is Box Hill’s 18th-century Italian fireplace, whose right-hand figure is a reproduction. The wrought-iron fire screen and other accouterments are Spanish. The wooden lions are believed to be Venetian.

To the right of the fireplace are a 19th-century European marquetry chest and a bench that is “straight out of Salem, Mass.,” says Samuel, noting that the entire space reveals Stanford’s penchant for mixing periods and styles.” The walls are covered in quarter-inch strips of split bamboo — White also had a penchant for experimenting with unusual materials.

“Stanford was really cheap,” says his great-grandson, using the walls of Box Hill’s dining room to prove the point. “If you couldn’t afford tapestries, you would have paneling, and if you couldn’t afford paneling, you would use Spanish leather. If you couldn’t afford leather, you would use lincrusta [a wallcovering made by spreading a paste of linseed oil and wood flour onto a paper base], and if you wanted something even less expensive, you used anaglypta, which is paper pressed to look like paneling.” Stanford chose anaglypta.

Repeated freezing and thawing — Box Hill had no heating system until 1938 — caused the paint on the anaglypta to develop a crackle finish. Samuel and his brother have no plans to redo it. “Removing the paint would destroy the paper, which is very thin,” Samuel says.

Hanging on one of the anaglypta-covered walls is a 19th-century American eagle mirror, restored several years ago for an exhibition in Newport. On what he calls “the Sheraton-style sideboard of no particular importance” are a bronze fish from a fountain Stanford designed for Box Hill and a cast of a 16th-century Florentine bust. Flanking the mirror are several faience plates.

ROSECLIFF

One of Stanford’s later works, this Newport mansion was commissioned in 1899 by Theresa Fair Oelrichs, a Nevada silver heiress, as a setting for elaborate parties. Stanford, his great-grandson says, “was able to express that spirit in architectural terms.” He modeled the exterior after the Grand Trianon at Versailles; inside is a mirrored ballroom with elaborate plaster ornaments. These days, the space is rented out for weddings and other celebrations. “If you have a party there,” Samuel says, “the room does half the work.” During Rosecliff’s heyday — the first Gilded Age — ladies would descend the heart-shaped stairway in their ball gowns, he notes, adding, “Its geometry is extraordinary. You’d need a computer to create it today.”

WILLIAM WATTS SHERMAN HOUSE

Starting at age 18, Stanford apprenticed with the acclaimed Romanesque revival architect Henry Hobson Richardson. In 1875, Richardson built his first great shingle-style house, in Newport, for the banker William Watts Sherman. Richardson died in 1876, and just a few years later, Stanford was asked to renovate the house by Sherman’s new wife, who wanted its interiors to be more formal.

Fitting neoclassical forms into a somewhat informal house was tricky. In the library, Stanford tied the elements together with a datum — a continuous line —18 inches below the ceiling. He outfitted the space with gold-leafed wooden panels, several carved into fish scales, one of his favorite motifs. “The abundance of gold leaf in this room makes it feel very special,” Samuel says.

KINGSCOTE

Kingscote, a Newport mansion that he enlarged in the 1870s for the King family of New York, represents another example of Stanford’s experimentation with exotic materials. The dining room ceiling is cork, while the panels flanking the fireplace are made of cast-glass blocks, and the wall above the fireplace is clad in iridescent tile.

Stanford had a great interest in built-ins, what Samuel calls “the middle zone between architecture and furniture,” as evidenced by a sideboard, which is integrated into the wainscoting but stands on legs. A spinning wheel, Samuel says, was the King family’s way of signaling that “we’ve been around a long time” — that is, a symbol of old money.

VILLARD HOUSES

For Stanford, “every surface was an opportunity, and few opportunities were neglected,” his great-grandson writes. A prime example is New York City’s Villard Houses, a complex of five townhouses that appears from the outside to be a single great palazzo. The building was commissioned in the 1880s by railroad magnate Henry Villard and completed in 1884 (with the help of McKim, Mead & White’s chief designer, Joseph Wells).

Although the houses were absorbed into a hotel — now the Lotte Palace — in the late 1970s (becoming a restaurant, meeting rooms, a bookstore and offices), their landmarked interiors have been preserved. A clock with bronze zodiac figures by the great sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens graces a marble wall in the main stairway, which was part of Villard’s own residence. Samuel believes the elaborate decorations — including marble column capitals, intricately carved wood and embossed-leather panels — were all executed in the U.S. “This was the period when the federal government’s main source of income was tariffs, and it was expensive to bring things over from Europe,” he says. “And there’s nothing millionaires hate more than having to pay money to the government.”

THE PAYNE WHITNEY HOUSE

The granite mansion commissioned by Payne and Helen Whitney at 972 Fifth Avenue contains what Samuel calls “one of the great rooms in America,” citing it as proof that his great-grandfather “never lost the ability to turn the volume up to the absolute maximum.”

The Venetian Room, Helen Whitney’s favorite, was where the couple’s guests waited. Its mirrored walls were topped with a cornice of basket-weave metal sporting delicate porcelain roses. Before she died, in 1944, Helen had it disassembled and stored in crates. In 1997, her son’s widow had it reinstalled in the building, now owned by the government of France. As a result, Samuel points out, “the Venetian Room escaped the most destructive period in American cultural history. If it hadn’t been in storage, it would probably have been cut up when they installed air-conditioning.”