January 6, 2018The subject of a new show at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, the Sea Ranch — a secluded, forward-thinking residential enclave on the coast of Northern California’s Sonoma County — got its start in the early 1960s, when real estate developer Al Boeke bought a 10-by-1-mile stretch of former sheep pasture (photo by Fred Lyon, © Lawrence Halprin). Top: A corner window seat with Pacific views in Rush House, a 1970 residence built by Charles Moore and William Turnbull, of the since-disbanded Berkeley, California, architecture firm MLTW (photo © Leslie Williamson).

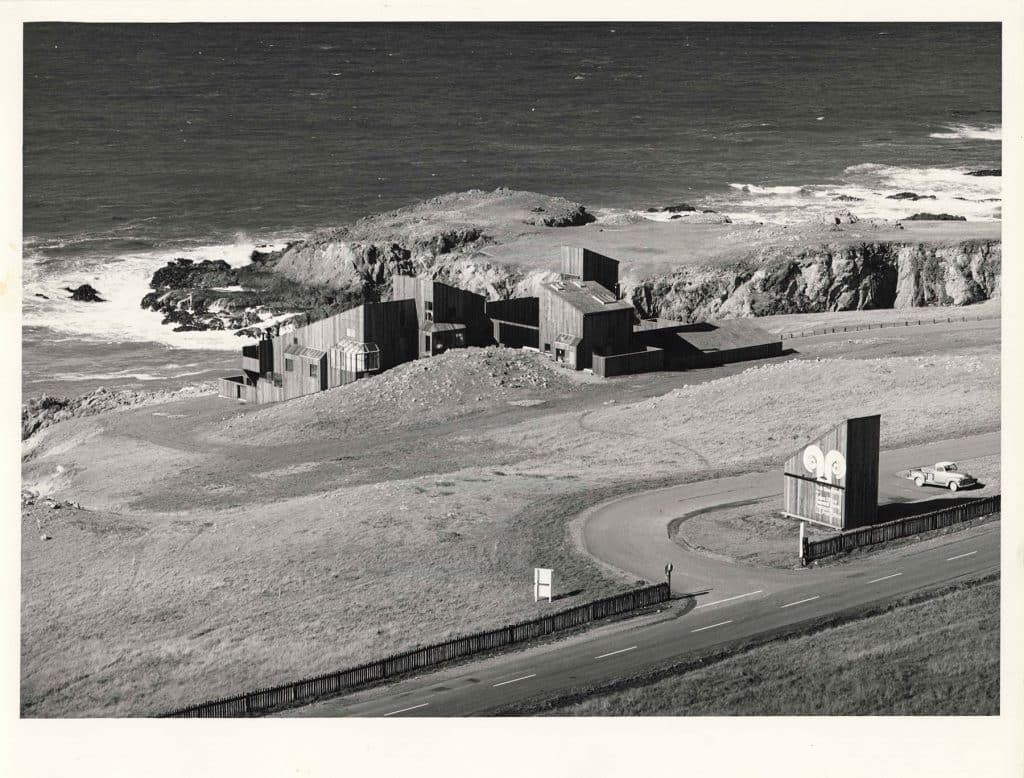

In 1965, MLTW designed the first multi-unit building on the property, Condominium One. Photo by Morley Baer, © the Morley Baer Photography Trust, Santa Fe

One of this planet’s most celebrated landscapes is the rugged shoreline of Sonoma County, three hours up the California coast from San Francisco, where undulating meadows and cypress forest meet craggy bluffs and pounding sea. But the existence of the Sea Ranch, an innovative early experiment in environmentally conscious development by a group of Bay Area architects and designers that opened on those dramatic bluffs in 1964, has remained a well-kept secret.

“It’s a very important part of modernist history and a story that’s not really been told,” says Joseph Becker, associate curator of architecture and design at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMOMA) and cocurator with Jennifer Dunlop Fletcher of “The Sea Ranch: Architecture, Environment, and Idealism,” which runs through April 28.

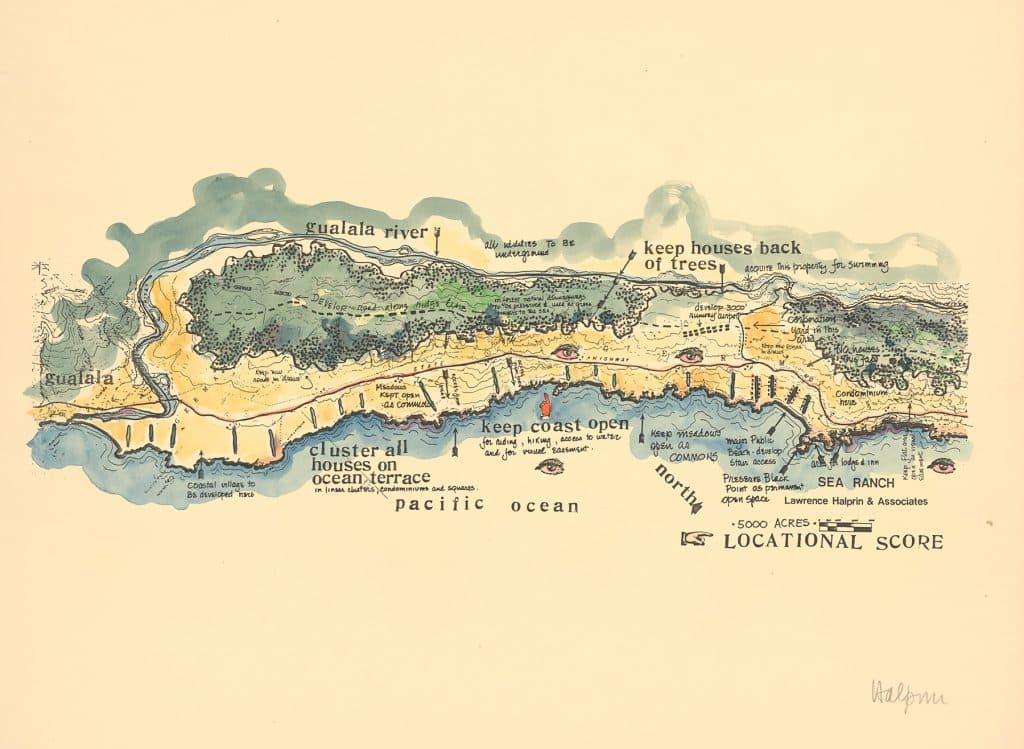

The exhibition explores the context, history, players, architecture and long-term impact of the utopian project, which began with the purchase by forward-thinking Bay Area real estate developer Al Boeke of a 10-by-1-mile stretch of coastline comprising 3,500 acres of former sheep ranch. A staunch opponent of suburban sprawl, “he was so taken with the beauty of the landscape,” says Becker, “that he came up with a business plan for it,” albeit one not as unconventional as the Sea Ranch became.

Boeke hired San Francisco–based architect Lawrence Halprin — who later designed Ghirardelli Square and United Nations Plaza, both in San Francisco, and Freeway Park, in Seattle — to create a master plan for a community that would meld affordable living with modern architecture and a shared commitment to living lightly on the land. Halprin envisioned a gatehouse, lodge, general store and restaurant; these would be simple modern structures built of local woods, including redwood and Douglas fir, that set the template for the rest of the development. Joseph Esherick, founder of the College of Environmental Design at UC Berkeley and nephew of master furniture craftsman Wharton Esherick, came on board and designed a series of single-family homes inspired by the plain forms of the region’s vernacular wood-sided barns and sheds.

Architect Joseph Esherick (inset) — who started UC Berkeley’s College of Environmental Design and was the nephew of furniture designer Wharton Esherick — designed the Sea Ranch’s Joseph Esherick in 1966.

“Esherick designed the first few homes tucked into the cypress trees with rooflines having a slope ratio believed to provide the best way for wind to pass over the buildings and cause the least disturbance,” says Becker. This was just one of a long list of architectural and landscape decisions, from modest home sizes to native plantings, that put the Sea Ranch way ahead of its time in environmental sensitivity. Its founders, says Becker, “were in deep awe of the site, its aesthetics, climate and history. There weren’t many projects so intent on preservation of the landscape as a core factor, so this was groundbreaking.”

Next, the upstart Berkeley-based team MLTW — consisting of Charles Moore, Donlyn Lyndon, William Turnbull and Richard Whitaker — designed prototype condominium units and a recreation center before disbanding, with the members going their separate ways (Moore became dean of the Yale School of Architecture). Condominium One, as the first group was called, consisted of 10 compact, 500-square-foot units that were arranged around a central courtyard to encourage communal living and priced to attract buyers from various income levels.

They were based on the cube, with individual variations to respond to the particular siting — a window bay to capture a view, say, or a nook for a bed. Exposed posts and beams and exterior siding of rough-hewn timber were meant to blend into the surrounding landscape. Extensive built-ins, including lofted beds, benches and tables, left little need for additional furnishings.

The Sea Ranch’s visual identity, from its logo to trail signage to marketing materials, was masterminded by graphic designer Barbara Stauffacher Solomon, who had trained at Switzerland’s Basel Art Institute and brought a touch of European modernism to the California coast. She developed the primary colors and bold shapes of the painted wall decorations in the Sea Ranch’s recreation center as a frugal way to work within a limited budget, but her designs would become widely copied forerunners of the environmental supergraphics that were a craze in the late 1960s and ’70s.

During the Sea Ranch’s heady first decade, its developers hewed closely to its stated ideals. “Homes were inexpensive, there was diversity in ownership, and stewardship of the land was a priority,” says Becker. “It was a beautiful example of nineteen sixties countercultural idealism.”

By the 1970s, however, residents of inland communities had become alarmed by the prospect of the Sea Ranch’s limiting public access to the beach — sacrosanct in California — and the state’s coastal commission declared a 10-year moratorium on building. Development resumed in the 1980s. In ensuing decades, with different developers at the helm and with the California real estate market heating up, some of the first principles “stretched a little bit,” says Becker.

“There are aspects in keeping with the original intention and aspects that have moved away from it. The desire for sixt-hundred-square-foot footprints was down, and the buildings grew a bit, and the intention for the houses to be tucked into the forest shifted,” he explains, adding, however, that “there’s still a lot of attention paid to having the buildings keep a cohesive design vision and to making it a priority to preserve the landscape.”

Wood wraps not only the outside of the Sea Ranch’s residences but also — as can be seen in 1970’s Rush House — a large part of the interiors, too, the better to blend in with the landscape. Photo © Leslie Williamson

Today, the Sea Ranch’s 2,300 one-acre lots are three-quarters built out. One can still buy or build a house, as fashion designer Trina Turk and visual artist Pae White have done in recent years, if the plans meet the requirements of the Design Review Board, some of whose members have long histories at the Sea Ranch. Original architects Lyndon and Whitaker still maintain homes there, as do the heirs of Moore and Halprin. (More recently, such architects as Kay Kollar, Tom Marble and Judith Sheine have done lovely work in the community.) When existing houses come on the market, Becker says, architecturally significant and bluff-edge properties are priced in the $1 million–to–$3 million range, with smaller homes in the neighborhood of $500,000 to $600,000.

The carefully considered artifacts in the SFMOMA exhibition include photographs, drawings, plans and a full-scale replica of a portion of Condo 1, Unit 9, which was owned by Moore. “We included a replica to show that the raw materiality was closely tied to the site and that construction techniques were relatively rudimentary — and, of course, to give a sense of scale,” Becker says.

Although some parts of the project are open to the public — including a seasonal lodge, a restaurant, a store selling sundries and Sea Ranch–branded merchandise and short paths to six coastal access points — most of its roads and extensive hiking trails are off-limits to nonresidents. And that is all the more reason to catch the SFMOMA exhibition: It offers a fascinating, in-depth look at a visionary community that would be hard to see any other way.