June 21, 2020When COVID-19 hit, some viewers of Skylar Fein’s most recent gallery exhibition came to him to say the work had been eerily prescient. The show, which took place last fall at Jonathan Ferrara Gallery in New Orleans, where Fein lives, mostly comprised artfully crafted, commercial-style signs that Fein built with wood. Some of them lit up.

One was meant to look like a notice from the Department of Homeland Security at Newark Liberty International Airport: “Welcome to the United States, Your Execution Is Important to Us. Please Wait and Someone Will Kill You Shortly.” Another was an attendance log with moveable wooden numbers and categories that included Deported, Neutralized, Terminated, Lost Cause, Consigned to the Dustbin of History, Complete Obliteration.

“I’ve always been a connoisseur of bleak visions,” Fein says. “Even as I was making them, the signs seemed to have fallen out of some other world, maybe a Stanley Kubrick movie. There’s doom, but also a macabre humor.”

Fein has been making art that urges people to resist the status quo for more than a decade now, his style heavily influenced by punk and Pop art. He describes himself as an accidental artist. Fein grew up in New York City and, from an early age, was interested in challenging norms. He joined the Communist Party USA at age 13.

In college, he majored in Russian and spent a year, in 1988, in the USSR. “I wanted to see the workers’ paradise,” he recalls. “It was terrible.” After college, he spent years doing odd jobs: construction worker, baker, sous-chef. “At one point, I sanded the hulls of boats in a boatyard,” he says. “I spent most of my adult life in a state of lostness.”

In his 30s, Fein went back to school, as a premed student at the University of New Orleans, hoping to help people as a physician. That was 2005, right before Hurricane Katrina hit. The storm and flooding destroyed a large portion of his belongings, and he decided to make a table out of the wood debris he found on his street.

“It was a composed tabletop of colored boards, and it looked kind of constructivist,” he recalls. An architect down the block liked it and commissioned Fein to make something similar for him. More commissions followed, and soon he was exhibiting his work in galleries. In 2008, he had his first solo show, at Jonathan Ferrara.

That same year, Fein was invited to create an installation for the inaugural edition of Prospect New Orleans, a multi-venue event that, when it launched, was the largest biennial of international contemporary art ever organized in the U.S. (it has since become triennial). His piece explored a little-known incident in the city’s history: the 1973 UpStairs Lounge arson fire, in which 32 people died in a gay bar in the French Quarter — at the time, the biggest mass killing LGBTQIA individuals in the U.S.

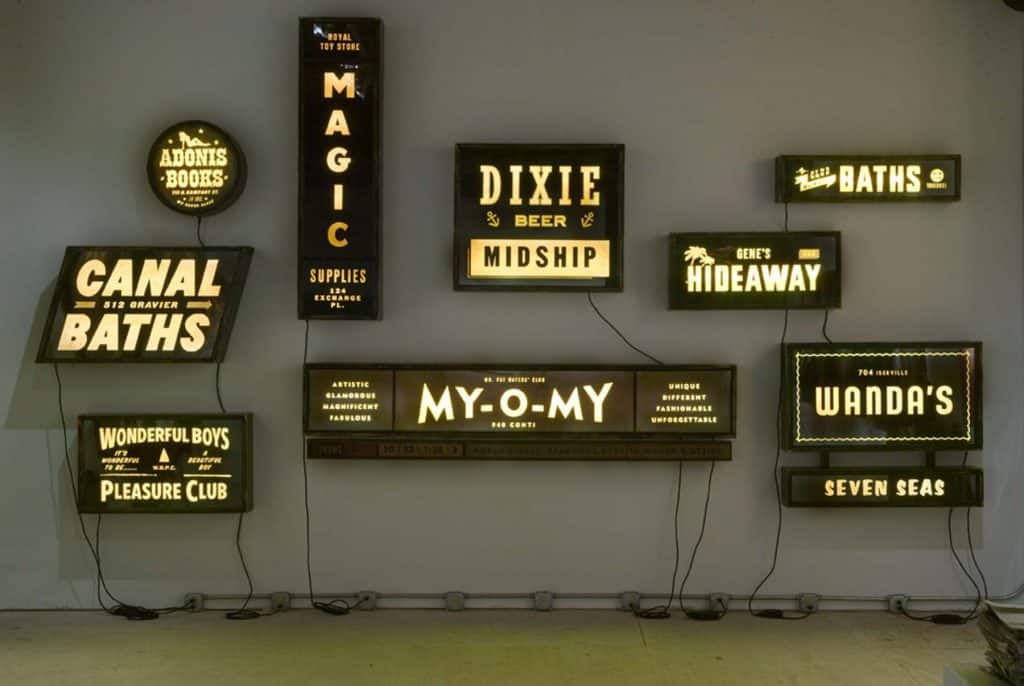

“How do you make art about that?” Fein recalls thinking. “I started out making respectful, well-mannered work about death, and that just made me dread going to my studio.” So, instead, Fein created an homage: Remember the UpStairs Lounge was a re-creation of the bar, complete with swinging doors, red damask-patterned wallpaper, loud 1970s dive-bar music, wood cutouts of Burt Reynolds and the swimmer Mark Spitz, a peep-show booth and lighted signs referring to other gay hangouts in the neighborhood.

Tens of thousands of people came through, and the response was overwhelming. A reviewer from Art in America questioned whether the work “met a strict definition of art.” Looking back, Fein exclaims, “That was truly a great review!”

Remember the UpStairs Lounge, which was acquired by the New Orleans Museum of Art and exhibited in 2018, was the beginning of Fein’s passion for signage. “I think signs have a lot of presence,” he says. “I love throwing a switch to make something light up.” In 2009, he had his first solo museum show, “Youth Manifesto” — a kind of ode to punk rock — at NOMA. Among the exhibits was a wood sculpture of an American flag composed of prices and advertising icons.

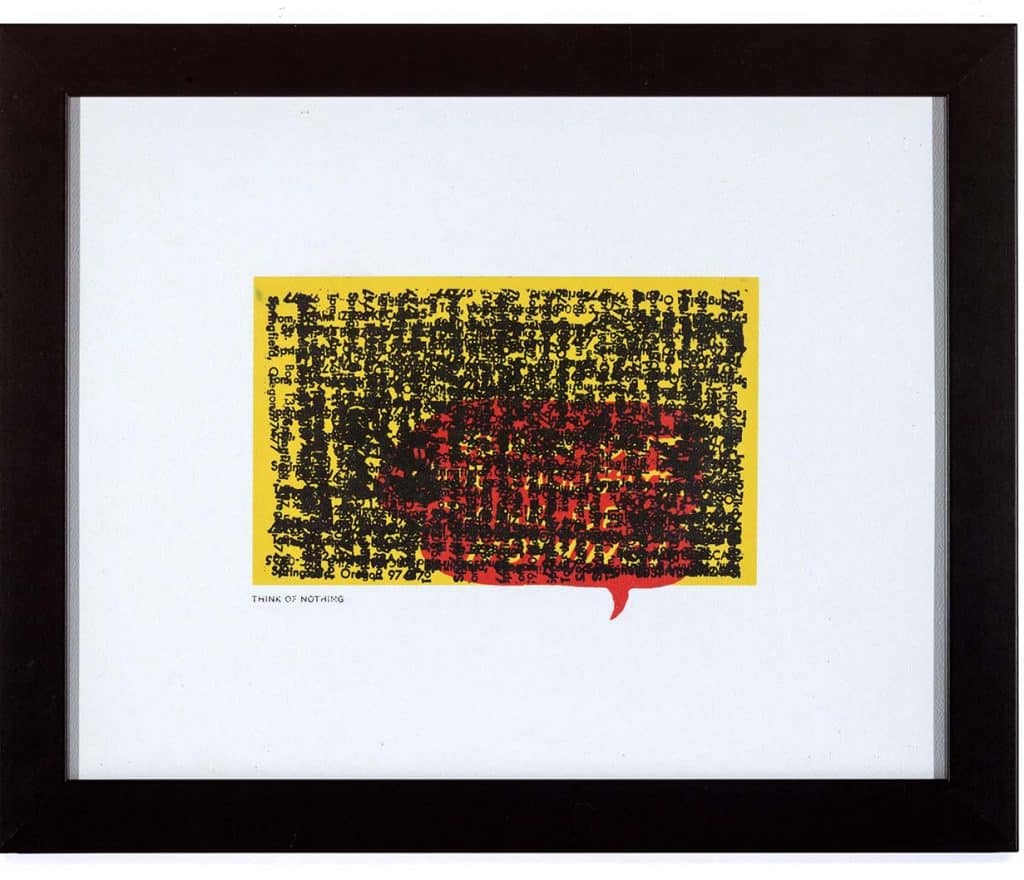

Fein has made several of these flags; the prices are juxtaposed with texts from radical writers, such as the French philosopher Georges Bataille and the labor activist Franklin Rosemont. “A lot of my work is on the border between fine art and design, and I’m okay with that,” he says. “A lot of political art was highly designed.”

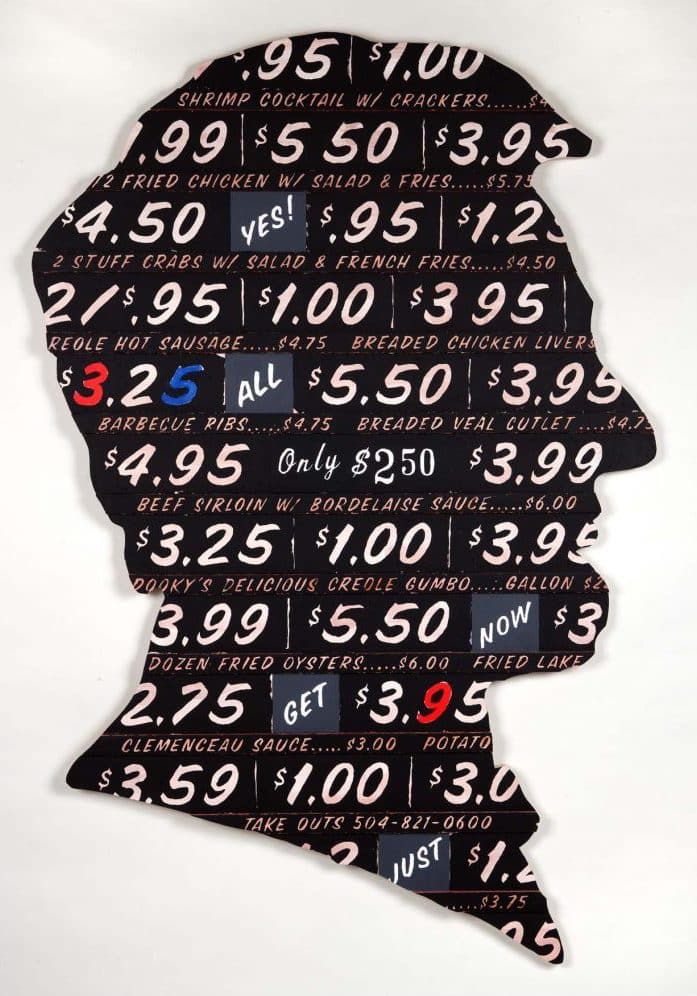

Fein took a similar graphic approach with a series of wood silhouettes of presidents. In Black Lincoln for Dooky Chase (2010), which was acquired by the Brooklyn Museum, Lincoln’s head is filled with prices, advertising icons and text from the menu of Dooky Chase, a New Orleans creole and soul food restaurant. It alludes to the suggested connection between Lincoln’s opposition to slavery and a trip he made as a teenager to New Orleans, then the center of the slave trade. Fein has also made silhouette sculptures of Nixon and Reagan.

In 2012, Fein had a solo show at C24 Gallery, in New York, called “Beckett at War,” for which he created numerous pieces inspired by Samuel Beckett’s time in the French Resistance. One is a painting of a telegram from the playwright’s friend Mania Péron warning him that the Gestapo were on the way (he fled to Southern France). “We all need to be tipped off the way that Mania Péron tipped off Beckett,” Fein muses. “We need people to lay some truth on us.”

Fein’s 2019 exhibition — the one that people now find prescient — was titled “Two Thousand Words for Students, Artists, Workers, Owners and Everybody,” an allusion to the Czech writer Ludvík Vaculík’s critique of life under Communism, “Two Thousand Words to Workers, Farmers, Officials, Scientists, Artists and Everyone.”

Among the pieces displayed were a lighted church-style sign, Daughters of Barbarity: Where the Beatings Will Continue Until the Unusual Occurs and Miracles Happen, and a mirror emblazoned with the words “I Have a Reason for Everything I Do.”

With its themes of brutality and authoritarianism, the show seems to have anticipated the country’s current state of pandemic-induced anxiety and unrest related to racial injustice.

Fein insists that his mission is to find beauty in a desolate world. During the pandemic, he hasn’t been making art; instead, he’s been helping to build acrylic barriers for local restaurants so they can safely serve customers.

“I hope my work reminds people that we’re not the first to live through hardship,” he says. “We can take courage from folks like Samuel Beckett. In the worst conditions, the memory of people like him steadies my resolve.”