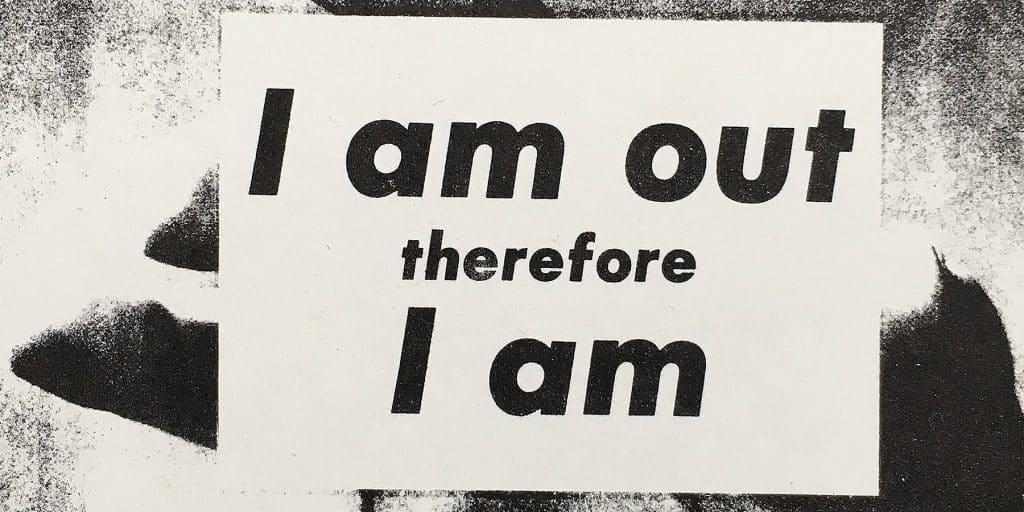

June 23, 2019This Fred W. McDarrah photograph captures young people celebrating after the 1969 riots outside the Stonewall Inn. Courtesy of Fred McDarrah Archive/MUUS Asset Management Co LLC. Top: I Am Out Therefore I Am, 1989, by Adam Rolston

When police stormed the Stonewall Inn, a bar frequented by gay men and lesbians, on June 28, 1969, no one knew that history was being made. “It took a couple of days for the mainstream press to pay attention, and then often disparagingly,” says Patty Rhule, a founding editor of USA Today who became a leader of Washington, D.C.’s Newseum in 2007. But the events of June 28 to July 1, now known as the Stonewall riots, proved to be the kick-off and catalyst for 50 years of social change. (So much change that this month, New York City Police Commissioner James O’Neill apologized for the raid.)

Some of that change was instigated or aided by artists who documented, meditated on and fought to improve the plight of sexual and gender nonconformists. Indeed, one of the effects of Stonewall was an unprecedented blurring of the line separating activists from artists.

That’s why it’s not just civil libertarians who are marking the 50th anniversary of Stonewall. Museums across the country are mounting exhibitions of art inspired by, related to and celebrating Pride, the movement launched in the wake of the riots. Here, some of the most intriguing offerings.

“Art After Stonewall, 1969 to 1989”

Leslie-Lohman Museum and Grey Art Gallery,

New York, through July 21

Left: Marsha P. Johnson at the Gay rights demonstration, Albany, New York, 1971, by Diana Davies. Right: Riot, 1989, by Gran Fury. Courtesy of Carpenter Center for Visual Arts /

Harvard Art Museum

When Charles Leslie and and Frederick Lohman realized there was a public interest in seeing and collecting art by and about gay men, the only place they could show it was their Soho loft, where they began mounting groundbreaking exhibitions 50 years ago. In 1987, they formed the Leslie-Lohman Gay Art Foundation. In 2016, the foundation became an accredited museum, which now occupies a storefront space on Wooster Street.

But even at 5,600 square feet, the Leslie-Lohman Museum isn’t big enough for the new exhibition “Art After Stonewall, 1969 to 1989.” Comprising more than 250 works by 160 artists, the show is divided between the museum and New York University’s Grey Art Gallery a few blocks away.

Grey is part of New York University, which is one indication of the acceptance queer culture has begun to receive from mainstream institutions. Indeed, “Art After Stonewall” was initiated in the American Heartland when the director of the Columbus Museum of Art asked Jonathan Weinberg, a painter and art historian who specializes in LGBTQ works, to help organize a show marking the Stonewall anniversary. “With extraordinary courage and generosity,” Weinberg says, “Columbus not only sponsored the exhibition but decided that, given its topic, it should open in New York.”

Art After Midnight (New York), 1985, by Tseng Kwong Chi. ©Muna Tseng Dance Projects, Inc.

In New York, the show is divided chronologically, with the Leslie-Lohman Museum displaying mainly works from the 1970s and the Grey mostly pieces from the 1980s. A large David Hockney painting of trans actress Divine and a Keith Haring poster created for National Coming Out Day are two highlights of the first part, along with pieces by Robert Mapplethorpe, Kate Millett, Barbara Hammer, Harmony Hammond and Michela Griffo. Significant artists in the Grey show include Vaginal Davis, Andy Warhol, Nan Goldin, Lyle Ashton Harris, Greer Lankton, Martin Wong and David Wojnarowicz.

The mixed-media artist Thomas Lanigan-Schmidt, who has colorful, tabletop-size sculptures in both sections of the show, was himself at Stonewall and succinctly sums up its cultural and historical significance in the catalogue: “The Stonewall event itself is like high art. . . . It’s one of those moments where reality and everything come together to create history.”

“Art After Stonewall” will remain at the New York locations until July 21, then move to the Patricia & Phillip Frost Art Museum, in Miami (September 14, 2019 – January 6, 2020), followed by the Columbus Museum (February 14 – May 17, 2020).

“Nobody Promised You Tomorrow: Art 50 Years After Stonewall”

Brooklyn Museum, through December 8

The Hudson River Jordan, 2018, by Tuesday Smilie

The Brooklyn Museum, long a center for art with an edge (it houses the Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art), has brought together pieces by LGBTQ artists born after 1969. Creating in the wake of Stonewall, says museum director Anne Pasternak, “these younger artists have worked to explore its impact, further its legacy and expand upon its mythologies.”

Notably, the museum commissioned L.J. Roberts to produce a monument to Stonewall. The resulting handsome assemblage of acrylic light boxes, dominating a large gallery on the fourth floor of the museum, commemorates women who took part in that uprising and other early protests. Long overlooked, they get additional shout-outs from Tuesday Smillie, in her banner made of delicate fabrics and plastic tarp; and in the terrific film Happy Birthday, Marsha, by Sasha Wortzel and the artist Tourmaline, formerly known as Reina Gossett, about trans pioneer Marsha P. Johnson (the title of the exhibition was said to be Johnson’s rallying cry). You’ll wish it lasted for more than 14 minutes.

Other highlights include a colorful painting by Jeffrey Gibson (seemingly abstract, it actually spells out its title, Because once you enter my house it becomes our house) and a sculpture made by Constantina Zavitsanos from a mattress pad literally impressed by sleep and sex, in a section of the show titled “Desire.”

“Stonewall 50”

Contemporary Arts Museum Houston, through July 28

Yaya Mavundia, Parktown, Johannesburg, 2014, by Zanele Muholi

The ambitious CAMH exhibition, curated by Dean Daderko, includes everything from the fragments of a resin-coated bar plastered with images of its patrons (salvaged from Mary’s, a Houston gathering place that closed in 2009) to color photographs by Los Angeles–based art-world star Catherine Opie of gender nonconformists like the poet Eileen Myles and the model Jenny Shimizu. There are many works by young artists not addressing Stonewall directly, Daderko says, but rather channeling the energy it created and “establishing dialogues across time and space.”

Cadre, a commissioned wall painting by Chitra Ganesh, invents a meeting of female protestors, their images embellished with faux hair, mirrors, fabric and found objects. Also in the show, in seeming dialogue with Opie, are 15 black-and-white portraits of South African queer and trans women by activist and artist Zanele Muholi.

The history of protest intersects with the history of pop culture in surprising ways. Jean-Michel Othoniel’s blown-glass sculpture Yellow Brick Road is an elegant and somewhat menacing tribute to the gay icon Judy Garland (whose funeral was held hours before the Stonewall riots). Nick Vaughan and Jake Margolin have contributed a five-channel video in which drag queens lip synch important gay rights speeches. “Making an exhibition that celebrates a riot that took place in New York’s Greenwich Village fifty years ago feels vitally important right now,” Daderko writes in the catalogue, adding that the artists “show us how to imagine a future in which the fight to represent ourselves and call the shots is no longer a necessity, but a pleasure.”

“Pride: Photographs of Stonewall and Beyond”

Museum of the City of New York, through December 1

Fred W. McDarrah photographed the historic gay pride march on July 27, 1969. Courtesy of Fred W. McDarrah Archive/MUUS Asset Management Co LLC

Fred W. McDarrah, a longtime staff photographer for the Village Voice, captured the aftermath of the Stonewall riots in precisely 19 images. “Someone once said, ‘You were at the battle of Lexington and Concord. Why didn’t you take more?’ ” recalls the photographer’s son, Timothy McDarrah. “My father answered, ‘Who knew?’ ”

McDarrah knew more than most. Following Stonewall, he shot countless Pride parades, city council hearings, rallies and other milestones of the gay rights movement. And he didn’t leave his negatives to moulder.

The photographer, who had a makeshift darkroom in his family’s Greenwich Village apartment, had created some 40,000 prints by the time he died, in 2007, all neatly catalogued, according to his son. “At the time, there was no demand from museums for photos of transexuals, of drag queens marching through the Village,” Timothy says. “But he knew these people, as ostracized and marginalized as they were, had value, and he made these prints knowing someday the world would catch up.”

Now, it has. The solo show “Pride,” at the Museum of the City of New York, features 11-by-14- and 16-by-20-inch prints made by McDarrah, as well as 6-by-8-foot blowups made by the museum. Nearly a dozen other institutions, finding McDarrah’s work essential to telling the story of queer liberation, have included it in Pride-related shows.

“He’s having a moment,” Timothy says of his father, adding, “He wouldn’t say, ‘I told you so,’ because he was a humble guy. He would smile and wink to himself.”

McDarrah captured this view of paradegoers during the fifth annual Christopher Street Liberation Day march at Gay and Christopher Streets in June 1973. Courtesy of Fred W. McDarrah Archive/MUUS Asset Management Co LLC

“Rise Up: Stonewall and the LGBTQ Rights Movement”

Newseum, Washington, D.C.,

through December 31

Harvey Milk campaign poster from his successful 1977 run for the San Francisco Board of Supervisors

A rainbow flag in its original colors signed by Gilbert Baker, the rainbow flag creator

“You really get to see how attitudes have changed over fifty years,” says Patty Rhule, describing the original exhibition she helped organize for the Newseum, which looks at how the media have portrayed key events in LGBTQ history, and helped or hindered its progress.

“One of the themes is how people used the power of the press to make the case for change,” says Rhule. But the show is more than just press clippings and videos. Artifacts on display include Martina Navratilova’s tennis racket; a campaign poster from Harvey Milk’s successful 1977 campaign for the San Francisco Board of Supervisors; the gavel Nancy Pelosi used to announce the repeal of Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell in 2010; and an early rainbow flag signed by its designer, Gilbert Baker. After the show closes (and the Newseum leaves its current home in Washington) at the end of the year, the exhibition will travel to other institutions.

“Letting Loose and Fighting Back: LGBTQ Nightlife Before and After Stonewall” and “By the Force of Our Presence: Highlights from the Lesbian Herstory Archives”

the New-York Historical Society, through September 22

Left: Say It Loud, Out and Proud: Fifty Years of Pride, ca. 1965–67, by Randolfe Hayden “Randy” Wicker. Right: The Future Is Female, ca. 1980s

Gay Liberation, 1970, by Su Negrin, Suzanne Bevier and Peter Hujar

“Letting Loose and Fighting Back: LGBTQ Nightlife Before and After Stonewall” contains important artifacts — the original street sign from the gay club Paradise Garage, a matchbook from the lesbian bar Sea Colony — as well as material that puts them in context. Bars and discos, the museum’s web page points out, were important to the gay rights movement as “oases of expression, resilience, and resistance . . . hard-won in the face of policing, unfavorable public policies, and mafia control.”

A companion show, “By the Force of Our Presence: Highlights from the Lesbian Herstory Archives,” focuses on the contributions of women to queer liberation, drawing on items from the archives of the title, long housed in a Park Slope, Brooklyn, brownstone. Notable among these are a 1970 poster, titled Gay Liberation, whose celebratory design by Su Negrin combines a joyful protest photo by the important gay artist Peter Hujar with a psychedelic mandala by Suzanne Bevier; and a pair of red, white and blue Doc Martens worn by the Lesbian Avengers’ Christina McKnight in an early 1990s Dyke March.