September 6, 2020He has galleries around the world — New York, Singapore, Hong Kong and soon London — but for contemporary art dealer Sundaram Tagore, the term global has a far deeper meaning. Born and raised in Kolkata to a culturally distinguished family, the Oxford-trained art historian has lived in more places than most people will visit in their lifetimes — from the Himalayas and Venice to Hong Kong and New York, where he’s now based.

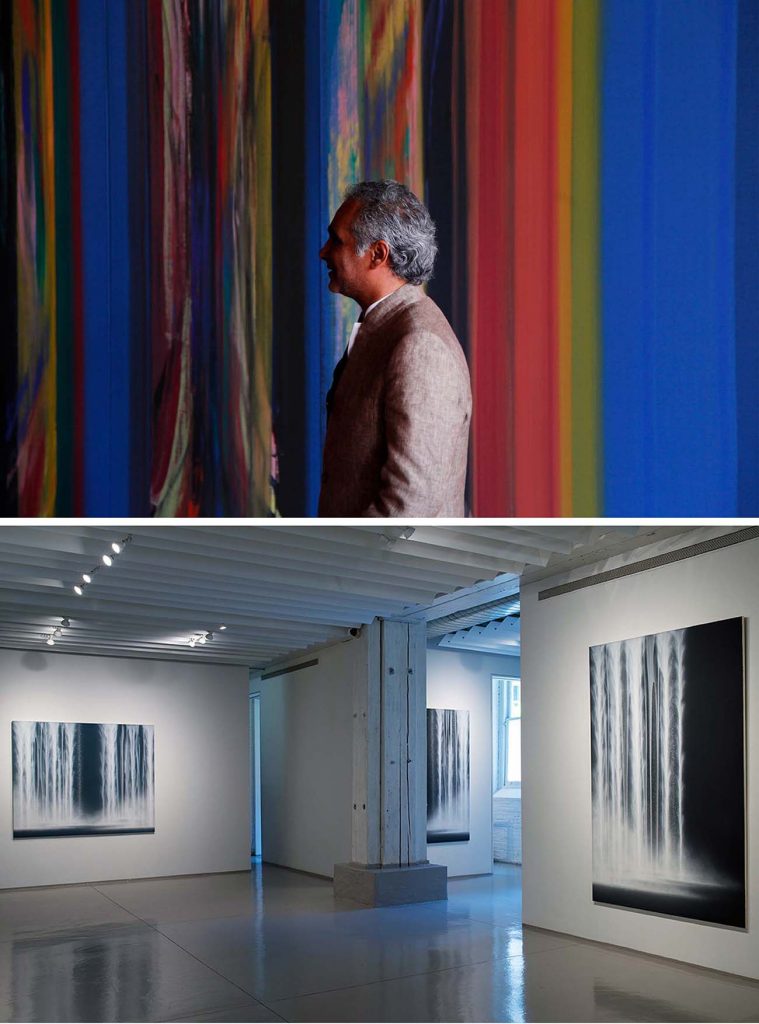

Since founding his first gallery space — in New York’s Soho in 2000, after working as a director at Pace Gallery — he’s developed a program steeped in cultural cross-pollination, paying particular attention to the many ways that artists respond to modernism through ancient and regional traditions — a fixation of his. He shows the work of a wide range of international artists, from Japanese painter Hiroshi Senju, to photographer Sebastião Salgado, to New York School painter Susan Weil.

Tagore’s appreciation for cross-cultural art extends to cinema, and he has made several films. His most recent production, the 2017 documentary Louis Kahn’s Tiger City, recounts the previously untold story of the legendary modernist architect’s massive National Assembly complex in Dhaka, Bangladesh, begun in 1961 and completed in 1982, nearly a decade after Kahn’s death. He’s currently working on a fictional film about a family of Indian Jews who flee their country during the tumult of the 1970s and open a contemporary art gallery in Manhattan.

While much of the work Tagore shows is highly aesthetic, for him, art does far more than provide pleasure or entertainment — it also enables a better understanding of the problems posed by globalization. In “Frontiers Reimagined,” a major show he was invited to cocurate at the Venice Biennale in 2015, for instance, he brought together more than 40 artists from 25 countries to explore solutions to the global crises we now face, from environmental degradation and poverty to the rise of nationalism and the oppression of women.

“I think many problems are rooted in this ongoing conflict between modernity and tradition,” he told Introspective in a recent interview. “To be modern, we have to give up some traditions.” Read on for more from Tagore.

Your father, Subho Tagore, was a pioneering artist, and you are also a descendent of the influential poet, composer and painter Rabindranath Tagore — the first non-Westerner to win a Nobel Prize, in 1913. What else should we know about where you came from?

My father went to London to study art at Central College in the 1930s, and when he came back to India, he founded the first Indian art collective, called the Calcutta Group. In those days, Calcutta was not the backwater it is today — it was an intellectual capital and a financial capital, and the epicenter of the art world. Calcutta had hosted the first Bauhaus exhibition to travel outside of Germany.

All the maharajas were collecting art there. My father had all these interesting artists around him, including Jamini Roy, who Peggy Guggenheim collected when she went to India. The discourse was all about, How do you create a modern art? How do you become a modern individual? So all this rich history that exists — that’s the kind of space that these artists were working within.

I’ve seen you described in some older publications as an “Asian art specialist.” While you certainly have some Asian artists in your stable, that doesn’t seem quite accurate. Did you start out dealing Asian art?

Not at all. I’ve had a global roster of artists from the very beginning, and in 2000, actually, when I first opened the gallery in Soho, I was principally showing modernist women painters from New York: Susan Weil, Merrill Wagner, Joan Vennum. It was a very exciting time. I slowly adopted a larger program, but I still have an emotional attachment to the work of those women painters.

Are you especially drawn to abstraction?

Yes, but I’m also drawn to the hand of the artist. The haptic. Process and materiality are very, very important to me. Take the “Waterfall” paintings of Japanese-born mid-career artist Hiroshi Senju, on view now by appointment in an ongoing exhibition at my Chelsea and Madison Avenue galleries in New York. In them, you can see how the renowned painter — the first Asian artist to receive an honorable mention in the Venice Biennale, in 1995 — poured the paint and used multiple brushes. In the work of celebrated Bangladeshi artist Tayeba Lipi, whose pieces are in the Guggenheim Museum, you can see how she connects razor blades and also safety pins to make glittering sculptures.

You also get a sense of the hand in some of the important photographers we show. Take Karen Knoor. She shifts things around using a digital process. She’ll plant a tiger in a palace, for example. When you deconstruct the photo, you see that evidence of her hand.

You have a well-developed appreciation for the cross-cultural. What do you get excited about in particular when contemporary artists explore different cultural influences?

That synthesis can extend the language of art and push boundaries. If they come from a long tradition, I like to think about how they are using that tradition today. For instance, Senju uses the thousand-year-old Japanese Nihonga tradition of crushing seashells, minerals and pigment and then combining the result with animal-hide glue to create his own paint. But when he applies it, he paints in a gestural Abstract Expressionist manner. That fusion is so interesting to me.

The Korean artist Chun Kwang Young also applies Asian traditions to modernist abstraction, but in a very different way. How did he get there, and how does he make those huge sculptural abstractions?

His works really straddle the worlds of painting and sculpture formally, but they are also layered with history. He was studying at the Philadelphia College of Art in the early nineteen seventies and loved the Abstract Expressionist style, but he knew American artists had already carved out that area.

After moving back to Korea, he had occasion to go to a Chinese apothecary, where he was given traditional medicine wrapped in a pouch with a string. That was an epiphany for him.

He began wrapping little pieces of Styrofoam — to recycle the material and for longevity, he says — with pages from historical Asian periodicals and history books, and then gluing them to canvas. He aggregates thousands of them to create these undulating abstract forms and adds charcoal and coloration by using teas or dyes from flowers.

You’re closing your gallery in Hong Kong, as the city undergoes a transformation under Chinese rule, but you’re also opening a space in London, in the new development Cromwell Place, as soon as the pandemic allows. In the meantime, you’re keeping your program going at your New York galleries, by appointment. What should we look out for this fall?

We’re organizing a big show of abstract paintings on metal by Miya Ando, who got a lot of attention for wrapping the Versailles hotel in Miami during Art Basel a few years ago.

She’s also cross-cultural. She was born here, but she grew up in a Zen monastery in Japan, and her parents, who are Russian and Japanese, were swordsmiths. She watched them transforming metal into these forms. So that’s where this idea to work with metal comes from.

Some of these young artists really have this cross-cultural sensibility in their DNA. Globalization is the world we live in, and they are able to capture that sensibility, that zeitgeist.

Talking Points

Sundaram Tagore shares his thoughts on a few choice pieces