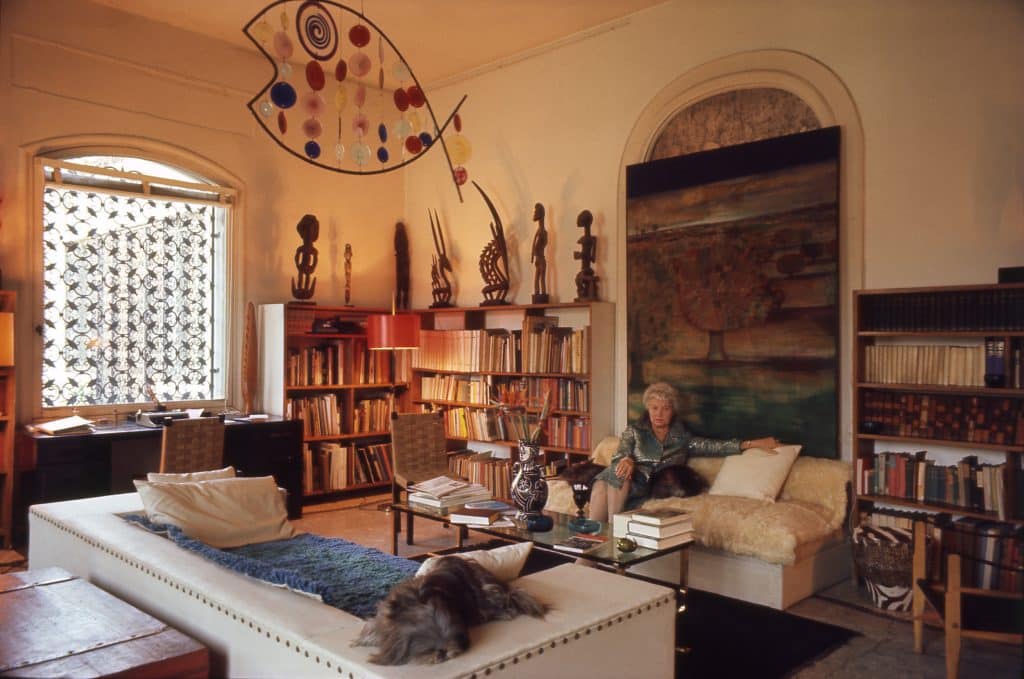

March 29, 2020A recent show at the Peggy Guggenheim Collection, in Venice, turned the spotlight on Guggenheim’s lesser-known collection of objects from Africa, Oceania and the indigenous Americas, which she often paired with modern art. Above, a D’mba headdress by a Baga artist in Guinea stands in front of a 1939 portrait by Pablo Picasso. Top: Guggenheim at home in the 1960s, in the library of the palazzo that now houses the museum, with works both tribal and modernist (photo courtesy the Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation). All photos by Matteo De Fina © Peggy Guggenheim Collection unless otherwise noted

In 1951, the storied heiress-turned-art-patron Peggy Guggenheim opened her palazzo on Venice’s Grand Canal to the public from Easter to early fall. For three days a week, strangers could stroll through rooms full of Pablo Picassos and Jackson Pollocks while she went about her daily business inside. By then, she had cemented her reputation as a fierce champion of Cubist, Surrealist, Dada and abstract art, one with a voracious appetite for the vanguard.

The visitors who flooded Palazzo Venier dei Leoni encountered spectacular works by Jean Arp, Constantin Brancusi, Alexander Calder, Leonora Carrington, Grace Hartigan, Kazimir Malevich, Henry Moore and Wassily Kandinsky, to name just a few. But they also were lucky enough to see the less-celebrated treasures elegantly packed into her home, which included her collection of objects from Africa, Oceania and the indigenous Americas.

As 1960s-era photos attest, Guggenheim gave these “non-Western” objects a prominent place in the palazzo, carefully pairing them with modernist paintings and sculpture whose creators habitually borrowed from such “primitive” forms while upending conventions of realism. It was a fashionable interior decorating scheme, but also an art history lesson.

Masks by (left) a Salampasu artist, in what is today the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and (right) a Toma or Loma artist, in what is now Guinea, flank a Tatanua mask (malangan) by a Madak artist, in Northern New Ireland, Papua New Guinea.

When Guggenheim died, in 1979, at the age of 81, her collection became part of the foundation that her uncle, Solomon R. Guggenheim, founded in New York in 1939, and most of her personal belongings, including her non-Western art collection, vanished into storage. Nine years earlier, she donated the palazzo.Since then, some of the pieces have been on view in the palazzo’s Cubist room, but it was only this year that the museum turned its curatorial attention to this meaty segment of Peggy Guggenheim’s collection in Venice. We can thank its relatively new director, Karole Vail, for that gift.

Guggenheim poses in the dining room of the palazzo to the left of the Umberto Boccioni sculpture Dynamism of a Speeding Horse + Houses, 1914–15. On the chests to either side of her are an Ago Egungun headdress (left), made in the first half of the 20th century by a Yoruba artist in what is today Nigeria, and Cactus Man I, 1939, by Julio González. Hanging on the walls are, from left, Abstract Speed + Sound (Velocità astratta + rumore), 1913–14, by Giacomo Balla; The Regular, 1920, by Louis Marcoussis; and Woman with Animals (Madame Raymond Duchamp-Villon), 1914, by Albert Gleizes. Photo courtesy the Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation

When Vail — an accomplished curator who also happens to be Peggy Guggenheim’s granddaughter — took the helm of the Venetian institution in 2017, she began pulling back the curtain through special exhibitions and rehangings. “Part of the educational mission of the museum is to highlight lesser-known aspects of the collection,” she says. A great example is the recent exhibition “Migrating Objects: Arts of Africa, Oceania, and the Americas in the Peggy Guggenheim Collection” and its accompanying catalogue. The show opened this winter with 35 works that range from Dogon figures from Mali and a D’mba headdress from Guinea to a bark mask from the Northern Amazon, ancient terracotta Nayarit figures from West Mexico and funerary carvings from Papua New Guinea. “When I arrived in Venice nearly three years ago, I was keen to show these objects, as I wanted to delve further into the collection and better understand Peggy’s broader tastes and interests,” says Vail.

Two ancestor figures flank an architectural element from a ceremonial house; all three pieces were made in Papua New Guinea in the first half of the 20th century.

With this show, she got to do just that. Not long after it opened, unfortunately, the coronavirus temporarily closed the museum, and it remains unclear if it will reopen before June 14, the exhibition’s scheduled end date. Regardless of what happens, though, those 35 objects will have taken on a much more significant role within the museum’s vast holdings.

“I think this part of the collection was never taken quite as seriously, even by Guggenheim herself,” says Vivien Greene, the exhibition’s lead curator, who worked with a team of specialists. “People didn’t know how to fit it into the narrative, even though it has a big place within modern art.”

In an effort to move beyond the Eurocentric model, in which African, Oceanic and indigenous American pieces have been considered almost exclusively as muses for modernist artists, the team sought to shed light on each object’s individual history, from the cultural role it played before landing in Europe to the socioeconomic context that enabled its migration. “We are now able to look at these works not only for their beauty and expressive power but also for a better understanding of, and renewed respect for, their original contexts and purposes,” says Vail.

The objects above — from left, a seated male figure, a lidded container and a vessel — are by unrecorded Dogon artists in what is today Mali. Those on the left and in the center are probably from the first half of 20th century, while the one on the right may have been made as early as the 16th century.

Guggenheim, who moved to Venice from New York in 1947 after closing her fabled modern-art gallery, Art of this Century, began assembling this part of her collection relatively late in her life, in 1959. Returning to New York that year for the first time since taking off for Venice, she was eager to buy more contemporary art, but things had changed. “I was thunderstruck, the entire art movement had become an enormous business venture,” she wrote in her autobiography. Feeling she’d be priced out of the modernism market by investors with no authentic interest in art, she turned elsewhere. “In the next few weeks I found myself the proud possessor of twelve fantastic artifacts, consisting of totem poles, masks and sculptures from New Guinea, the Belgian Congo, the French Sudan, Peru, Brazil, Mexico and New Ireland,” she wrote. She returned to Venice with them and continued collecting through the notable dealers Julius Carlebach, in New York, and Franco Monti, in Milan.

Guggenheim, wearing a pair of her signature Elsa Schiaparelli sunglasses and holding one of her beloved Lhasa apsos, stands between the Yoruba Ago Egungun headdress (left) and the Tatanua mask from Northern New Ireland. Hanging in the middle of the wall behind is The Antipope, 1941–42, by Max Ernst, to whom Guggenheim was married for a time. Photo courtesy the Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation

Based on the photographs of the palazzo from the 1960s, it appears that Guggenheim was devoted to arranging and rearranging her objects, discovering formal resonances between her favorites. In one image, for instance, an elaborate polychrome Ago Egungun headdress from the first half of the 20th century — recently connected to a Yoruba artist in the workshop of Oniyide Adugbologe in present-day Nigeria — stands on a wood chest before a 1920 Cubist painting by Louis Marcoussis, a pairing that’s replicated in the exhibition. In a second photo, the sculpture sits on a pedestal surrounded by different paintings. Numerous other objects likewise appear in multiple places in her home in the photos, including an equestrian figure, also likely from the first half of the 20th century, by a Senufo artist in present-day Côte d’Ivoire, and a bark mask by a Cubeo artist from the Uaupés region of the Northern Amazon. Meanwhile, a male and a female figure, made by a Nayarit (Ixtlán del Rio culture) artist from ancient West Mexico between 300 and 400 BC, are displayed near a Picasso work in one photograph and next to a Wassily Kandinsky in another.

Guggenheim and the artists she cherished were largely unaware of the cultural significance of such objects; for them, the works’ exotic mystique and formal appeal were enough of a draw. The Surrealists, for example, found the pieces’ perceived mythical power especially important. André Breton, an avid collector of Oceanic works, once wrote, “From the beginning, the course of Surrealism is inseparable from the power of seduction, of fascination, that Oceanic objects exerted over us.”

The museum’s recent show replicated some of the pairings of non-Western and modern art that Guggenheim presented in her effort to emphasize the similarities of their abstract arrangements of form and color. L’Habitué (The Regular), 1920, by Louis Marcoussis, for example, was shown with the Yoruba Ago Egungun headdress. Research performed for the exhibition led to the headdress’s new attribution to an artist in the workshop of Oniyide Adugbologe.

Many of the objects were, indeed, originally used for ritual purposes, but the exhibition revealed stories beyond their ceremonial roles that make them even more fascinating. Guggenheim’s striking malangan carvings, from early-20th-century New Ireland, Papua New Guinea, for instance, were used in funerary ceremonies and meant to rot or burn after use. That they exist today speaks to a moment in the middle of the last century when the Western market for such pieces was strong enough to disrupt local traditions.

Guggenheim sits surrounded by her cherished collection in the library of her palazzo. Behind her hangs Autumn at Courgeron, 1960, by René Brô. On the bookcase to the left are African sculptures, and hanging from the ceiling is Fish by Alexander Calder. Photo by Ray Wilson, courtesy of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation

This funerary carving was made in the early 20th century by an unknown Mandara artist on Tabar Island, Northern New Ireland, Papua New Guinea.

Taken in their entirety, the holdings clearly have the intrigue and dazzle of great provenance; Peggy Guggenheim was vastly more adventurous than many collectors of her era. But the works she amassed are also a good reflection of popular taste at the time. In 1957, the Museum of Primitive Art was established across the street from New York’s Museum of Modern Art by Nelson A. Rockefeller and MoMA’s then-director Rene d’Harnoncourt.

Rockefeller’s collection of African, Oceanic and indigenous art included several types of objects that Guggenheim would later acquire for herself — among them, a striking Baga D’mba headdress from Guinea, used in ceremonial dances that the French colonial government had restricted. The Museum of Primitive Art also had Senufo zoomorphic helmet masks similar to Guggenheim’s wildly expressive example from present-day Côte d’Ivoire.

While Guggenheim may not have presented her non-Western objects with the fanfare she accorded her paintings and sculpture from Europe and the United States, these pieces were clearly very important to her. “She wrote about loving the work while she was collecting it,” says Greene. “She corresponded with a man who collected non-Western objects, Robert Brady, a Barnes student who settled in Cuernavaca. She writes, ‘I’m so glad I started collecting primitive art.’ ”