November 13, 2017In the course of his career, Ward Bennett designed everything from interiors to table settings to furniture, including the 1968 Scissor chair (photo by Michael Pateman/Herman Miller Archives). Top: Bennett reclines in a caned Mobius Executive armchair while resting his feet on a low-back, upholstered version (photo courtesy of Herman Miller Archives).

Long before Marie Kondo began evangelizing about the life-changing magic of tidying up, Ward Bennett had discovered the joys of paring down. “Most homes are just full of things that are meaningless,” he said in a 1981 interview with author and preservationist Barbaralee Diamonstein-Spielvogel. It was an unlikely stance for a designer of things ranging from interiors and furniture to textiles and flatware, but Bennett, a native New Yorker who died in 2003 at the age of 85, was a self-made Renaissance man with a contrarian streak.

He delighted in the art of living, the challenges of eliminating the unnecessary and the singularity of his own apparently boundless talents. Those talents have finally been chronicled, in a multifaceted monograph published by Phaidon this year, on the centenary of his birth.

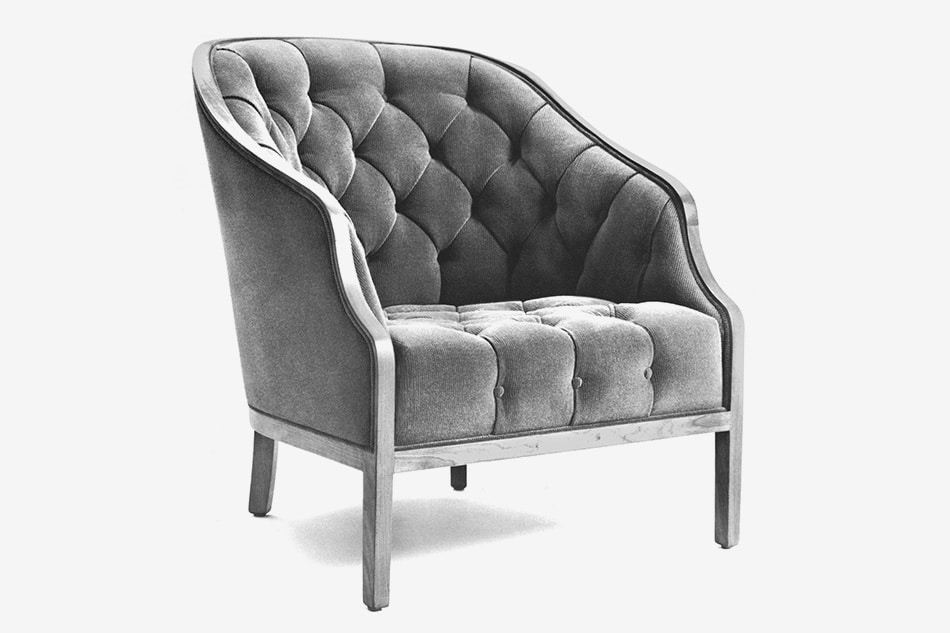

“Ward Bennett was a modernist, but one who had no qualms about embracing history,” says noted design journalist Pilar Viladas, who contributed an essay to the volume. “For me, his signature was his ability to quote history while making it modern.” She points to such examples as the Scissor chair of 1968, a modernist update of the 19th-century Brighton Beach chair. His Banker series lounge chair (like the Scissor, among the approximately 150 chairs he designed for Brickel Associates) was a streamlined take on the 18th-century French bergère and a Bennett favorite for its visible framing. “I expose the structure of everything I design,” he once said, “even of my chairs.” The revelations didn’t end there.

“What stood out to us was how transparent Bennett was about his influences,” says Elizabeth Beer, who coedited the lushly illustrated book with Brian Janusiak, her husband and fellow cofounder of the multidisciplinary design studio Various Projects. Bennett was always clear about the origins of his designs and where they ended up, she notes: “I don’t think he thought of himself as original in terms of the particular products he made as much as his approach to total design — designing every aspect of your life.”

At the Easton House in Easton, Pennsylvania, which Bennett designed in 1961, he is pictured leaning out of a hatch that leads to the kitchen, dining room, bathroom and guest bedroom. Photo courtesy of the Ward Bennett Archive / Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum; © Smithsonian Institution

“We loved the simplicity of his forms, the way he approached things — very physically, almost sculpturally — and how he didn’t let specific categories or disciplines fence him in,” adds Janusiak. “He was very comfortable using his sensibilities as a designer and his aesthetic understanding of how he liked the world to be to design anything that he became interested in.”

The sheer breadth of those interests, combined with what Bennett described as “complete devotion” to whichever of the “many, many professions” he was working in at a particular moment, fueled an astonishingly diverse yet utterly cohesive body of work for clients including David Rockefeller and Chase Manhattan Bank; Tiffany & Co.; Rolling Stone publisher Jann Wenner; and Gianni and Marella Agnelli, for whom he created a minimalist apartment in a Roman palazzo. Whether designing a beach house or an ashtray, he sought “to make the form as poetic as possible.”

Born in Manhattan’s Washington Heights neighborhood, Bennett left home and school at age 13, a decision he ascribed to tumult stoked by his father, an intemperate vaudevillian. He found work schlepping silk in the Garment District, then began assisting fashion designers. While still a teenager, he was dispatched to Europe (aboard the Normandie, first class, no less) to sketch the latest collections and bring back fresh ideas. Soon after, he returned to Europe and traveled extensively, seeking out people he admired (Constantin Brancusi, Le Corbusier) and soaking up other formative influences (Cistercian architecture, Rodin sculptures, everything in the Uffizi).

After a stint at I. Magnin in San Francisco and another in the U.S. Army, he returned to New York and in 1943 was hired as a window dresser for fashion entrepreneur Hattie Carnegie. (Her “way of living” fascinated Bennett. “Everything was beige and she had wonderful taste,” he recalled.) Meanwhile, he studied art with Hans Hofmann, palled around with Jackson Pollock and Tennessee Williams and shared a sculpture studio with Louise Nevelson. He later spent a year in Mexico making jewelry with Richard Pousette-Dart, and the Museum of Modern Art included Bennett’s bold brass necklaces and pendants alongside pieces by the likes of Anni Albers and Alexander Calder in its 1946 “Modern Handmade Jewelry” show.

Bennett designed the Sugarman House, a concrete residence in Southampton, New York, for CBS producer Marvin Sugarman and his wife, Ronnie, in 1969. He raised the home’s living areas to maximize views, like the one here, from the second-floor roof deck. Photo by Adrian Gaut

At age 30, he received his first interior design commission: a Fifth Avenue penthouse for Harry Jason and his wife (the sister-in-law of Bennett’s brother). The project received favorable press coverage, including a two-page spread in the New York Times, and suddenly Bennett had a new career. “I just was sort of shunted into it. I really think I may have continued with sculpture,” he said in a 1973 interview for the Archives of American Art (the full transcript appears in the book). With no formal training, he drew on his fashion industry experience, including window displays (“working with objects and lighting”) and an accumulated understanding of “elegance, and how people would live in a home.” His lack of formal training might actually have been a strength. “He didn’t come out of architecture school or industrial design school, and it gave him the freedom to do what he felt was necessary,” says Beer. “He just kind of made it up as he went along!”

This same individuality fueled a swift expansion of projects for Bennett’s one-man design firm (he worked from home — mainly the sky-lit Manhattan penthouse apartment he created in 1962 after acquiring a series of former maids’ rooms in the famed Dakota — and never employed more than an assistant or two). “I would not like to buy other people’s furniture [for interior design projects], so I would just go to some furniture shop and make a little sketch and keep my fingers crossed,” he recalled of his earliest forays into furniture design. These led to numerous commercial partnerships, including his 21-year role as the sole designer for Brickel Associates (acquired in 1993 by Geiger, which was acquired in 1999 by Herman Miller).

“Ward Bennett was a modernist, but one who had no qualms about embracing history.”

Rather than hone a signature look, Bennett made space and scale his primary concerns. Each commission represented a fresh opportunity to solve problems and address individual needs. A champion of industrial elements who is credited with originating the high-tech style (“Stainless steel is the precious metal of our time,” he once declared), he was equally enamored of natural materials. Bennett sneered when Skidmore, Owings & Merrill proposed the exclusive use of teakwood in Chase Manhattan’s executive offices. Having personally interviewed all 38 of the bank’s senior leaders, he was determined to offer curated choices of furniture, objects, artwork, even wood. “We ended up with great problems using four types of wood. It was sort of a battle,” he said later of the 1960 project. “It was worth it, because it’s still a very good job.”

Here, Bennett shapes the arm of a carved-wood frame chair. “He began his career in fashion and recognized the influence that experience had on his process of furniture ‘patternmaking’ and modeling,” according to the book. Photo courtesy of Herman Miller Archives

“His approach was very hands-on,” says Janusiak. “He went to the factories, worked with the craftspeople, made models. In the case of a chair, he would create a basic wood model with cardboard and fabric, position it around his body and figure out the angles and what made it comfortable and how things needed to change, and then make new models.” He happily delegated the drafting of technical drawings to others, including Norman Diekman.

“He was a classic American success story,” notes Viladas, “albeit one of creativity more than business acumen.” Day-to-day operations, finances and “selling products” were among the myriad things in which Bennett said he had no interest. He also steered clear of professional associations (“I’ve never been a joiner”). In the 1973 interview, he professed to hate decorating and decorators, social climbing and television commercials. Travel sustained him, as did meditation, film “and, of course, any of the arts.”

A great advocate of eliminating furniture (he is forever linked to the “conversation pit”), Bennett harbored a Zen-inspired goal to own nothing, yet his creative ambitions knew no limits. “If you’re a designer,” he said, “you should be able to design everything.”

Shop Ward Bennett on 1stdibs

Or Support Your Local Bookstore