December 19, 2016The design of this ca. 1815 Austrian Empire table was likely inspired by French architects Charles Percier and Pierre-François-Léonard Fontaine, who created the Empire style. Top: A detail of the table’s hooved triangular base shows carved-wood sphinxes, stained black to look like patinated bronze.

With particularly fortuitous timing, the Kunsthandel Stephan Andréewitch gallery in Vienna has an outstanding Austrian Empire center table for sale. It is in the same style as the exceptional furniture with bronze mounts that went on view November 18th in the exhibition “Charles Percier: Architecture and Design in an Age of Revolutions” at the Bard Graduate Center in New York (through February 5, 2017). The bronzes also recall the dazzling 18th-century mounts unveiled at the Frick Collection in New York in its new show, titled “Pierre Gouthière: Virtuoso Gilder at the French Court” (through February 19). Both shows will travel to France.

Made about 1815, the Andréewitch piece is a round tilt-top table whose three legs are adorned with winged sphinxes sitting on a triangular base. The top is veneered with 18 book-matched pie-shaped slices of highly figured Austrian walnut. The pedestal is stained black to simulate patinated bronze, as are the carved wood sphinxes. Affixed to the pedestal are gilded mounts in the form of palmettes and dancing maidens.

The table was made in the workshop of Josef Ulrich Danhauser, the owner of the most important furniture factory in Vienna between 1804 and his death, in 1829. Danhauser employed hundreds of artisans to make fine pieces for royal and noble patrons, as well as simpler Biedermeier examples for the middle class. (More than 2,000 Danhauser drawings, along with actual examples of the furniture, are archived in the MAK, the Österreichisches Museum für angewandte Kunst, Vienna’s design museum).

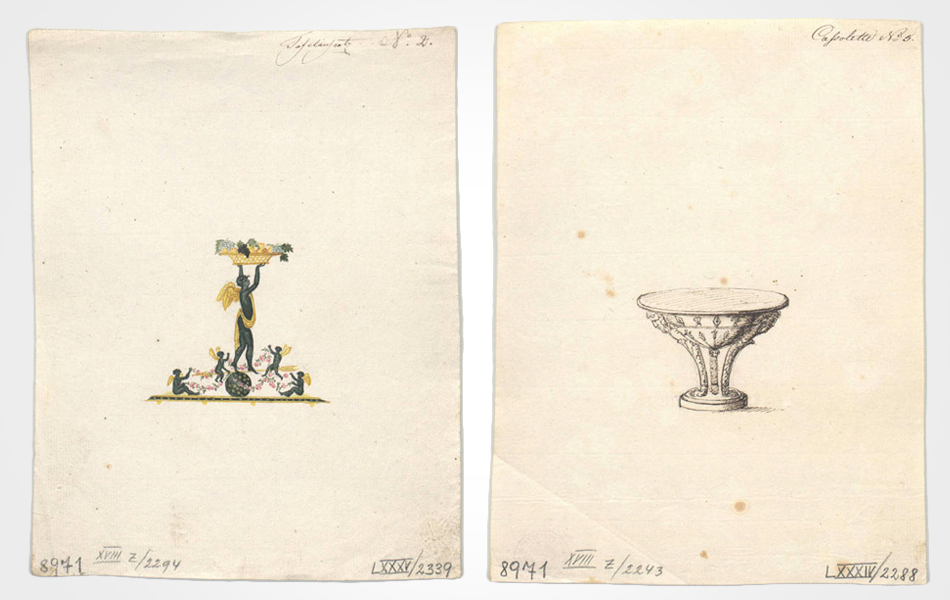

This drawing, from the 1812 Recueil de décorations intérieures, details a center-table design by Percier and Fontaine that inspired Danhauser’s piece.

But the Austrian center table is not a wholly original Danhauser design. Andréewitch is convinced that the table was inspired by a similar example created by renowned Paris architects Charles Percier and Pierre-François-Léonard Fontaine, who invented the Empire style in the 1790s. Both men admired classical aesthetics and lived in Rome, where Percier was on a five-year royal grant after winning the Prix de Rome. Upon their return, in 1791, at the height of the revolution, they set up a practice and began adapting ancient models to contemporary taste. The new style caught the attention of Joséphine and Napoléon Bonaparte, who became their primary patrons. Percier and Fontaine worked on numerous projects for the Bonapartes over the course of more than 10 years, decorating Malmaison, remodeling the Tuileries Palace, redecorating Fontainebleau and the Grande Galerie of the Louvre, creating the decorations for Napoléon’s coronation as emperor in 1804 and designing the Arc du Carrousel.

Although Percier and Fontaine collaborated closely, the Bard exhibition — the first devoted to Percier alone — posits that the former did most of the creative design and decorating work while the latter managed clients and the construction of projects. As the show’s guest curator and Sorbonne architecture professor Jean-Philippe Garric writes in the Bard catalog: “The importance of Percier’s work in interior decoration, furniture, metalwork and ceramics as well as in the graphic arts … sets him very much part from the other architects of his generation, indeed from architects in general.”

In 1801, Percier and Fontaine began publishing folios of their designs, including one of a round table with sphinxes at its base, for distribution across Europe. In 1812, the folios were collected and published as Recueil de décorations intérieures — the first recorded use of the term “interior decoration” — a copy of which is on display at Bard.

“It was the idea of the Danhauser workshop in Vienna to copy the French taste,” says gallery owner Andréewitch, who has reproduced the Recueil page showing the table from his personal copy of the 1812 volume on his 1stdibs storefront.

Rarity:

The table model is not particularly rare, but an example with such perfect proportions is. There are several illustrated in the Madeleine Deschamps book Empire (Abbeville 1994), which illustrates how the proportions of the table changed as it was copied by artisans in Italy, Spain, Germany, Sweden and Russia — and not for the better.

“This table is one of the best known and most important pieces Danhauser made,”Andréewitch says. “Museums in Austria and Warsaw, Poland, have examples of it.”

Condition:

“Most of these tables were made of mahogany, but this is Austrian walnut with exceptional figuring, and it is in nice original condition,” says Andréewitch, who thinks it’s notable for being made of local wood.

Provenance:

Andréewitch says the table was in the collection of a noble family from Genoa, Italy, before he bought it.

Price:

Andréewitch is asking $71,464.85 for the table, which he thinks is reasonable. “Another one sold for just over two hundred thousand dollars, a record price, at the Dorotheum auction house in Vienna six years ago,” he points out. (The buyer was Bernhard Rzehorska, a longtime collector of Empire furniture.)

He notes further that the table was a real luxury item when it was made: “A table like this would have cost about six thousand Austrian gilders in 1815. It was not affordable for the average Viennese citizen. The price was the same as a year of or two of salary of a government minister.”