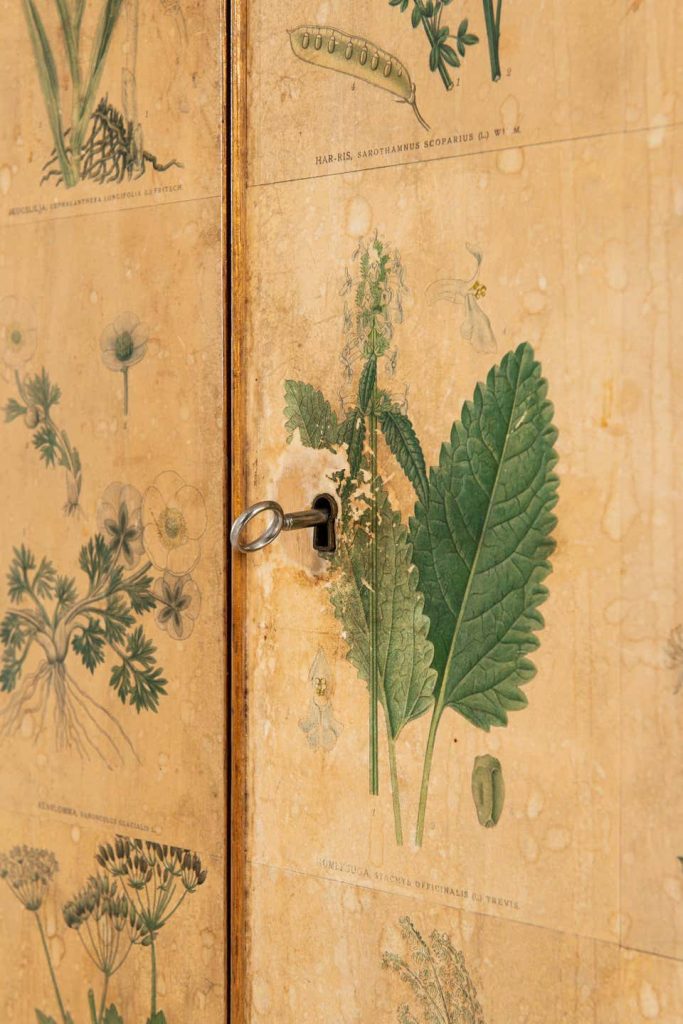

Josef Frank for Svenskt Tenn Flora Cabinet Model 852, 1937 ($114,556)

September 20, 2020

Architect and designer Josef Frank fled Austria ahead of the Nazis in 1933, bringing echoes of the warm woods and floral decoration of his native land’s Wiener Werkstätte tradition to his adopted Sweden.

Not a fan of the steely Bauhaus “machine for living” aesthetic, Frank has been called “the friendly modernist,” exponent of a gentle, humane variation on the style of which this rare first edition of his Flora model 852 cabinet is a sublime embodiment.

Designed in 1937 for the Stockholm-based furniture manufacturer Svenskt Tenn, where Frank was lead designer for three decades, the cabinet stands nearly six feet tall, crafted of mahogany and oak and covered with hand-colored paper inspired by 18th-century botanical drawings. It’s a standout example of Scandinavian modern’s prewar phase and of Frank’s unique artistry, says Claes Schalling, of Malmö, Sweden-based Studio Schalling.

Later models of the Flora cabinet, which remained a popular item in Svenskt Tenn’s catalogue, differ from this one in having a wooden plate behind the door handles. It’s not clear how many of the first version were made.

“My guess is fewer than a hundred,” Schalling says. And they’re easily distinguishable. “The layout of the hand-colored papers is never the same, which makes each cabinet unique.”

Ilse Crawford for Nanimarquina Wellbeing Hammock ($1,035)

The luxurious Wellbeing hammock is not something to leave out in the rain. It is woven by Nepalese artisans using traditional techniques and the purest cotton — organic, sustainable, hand-spun and undyed. “It’s definitely an indoor item, or for use on a covered porch,” says Scott Burns, vice president of the Barcelona-based rug and textile company Nanimarquina.

The hammock is the product of a collaboration between Nanimarquina and designer Ilse Crawford, of the multidisciplinary firm Studioilse. Crawford, who gained a cult following when she was profiled in a 2017 episode of Netflix’s Abstract: The Art of Design, founded the department of Man and Wellbeing at Eindhoven, Holland’s most prestigious design academy, and was a founding editor of the influential shelter magazine Elle Decoration UK. She and Nanimarquina share a humanist philosophy in which comfort, softness and warmth are of paramount importance. Beauty is a happy by-product.

Think of the hammock as a destination — a place to unwind in a den or sunroom, in lieu of a ho-hum couch or daybed. “It’s where you go for relaxation, to get away from everything,” Burns says. “Even five minutes in this hammock is enough to decompress.”

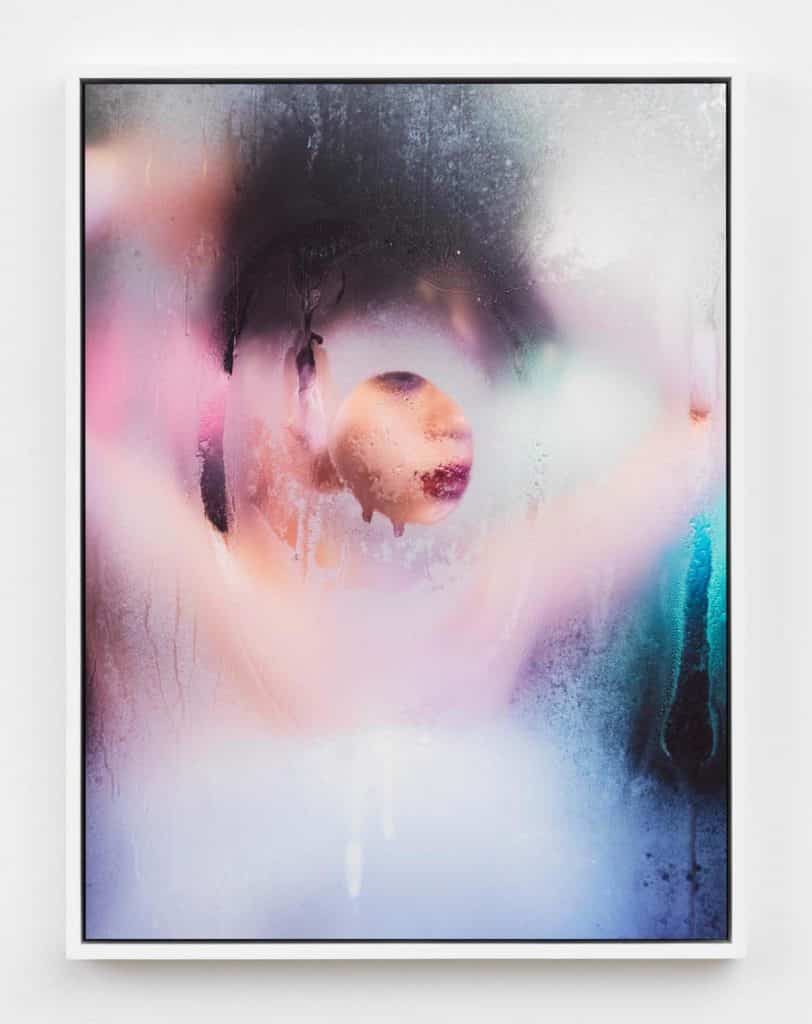

Target, 2017, by Marilyn Minter ($42,000)

Steamy in more ways than one and, measuring seven by five and a half feet, larger than life, Marilyn Minter’s C-print Target, 2017, has the blurred, enigmatic aura that characterizes the American artist’s sex-positive, feminist paintings.

The body of the model is obscured except for a circle cleared of condensation to reveal part of her face, as if she exists in a bulls-eye. The title alludes to global political threats to women’s reproductive rights and sexual freedom, longstanding concerns for Minter.

She first gained recognition in the 1980s with photorealistic paintings of pornographic images, intended to empower women, and her work has continued to push the boundaries of what defines female beauty and sexuality.

Alicia Pestalozzi, associate director of Lehmann Maupin gallery, calls the print, number one from an edition of three, “a prime example of Minter’s photographic oeuvre, examining many of the same ideas explored in her paintings: using steamed and frosted glass to obscure the viewing plane, reinterpreting voyeurism in art and reclaiming for women the portrayal of the female form.”

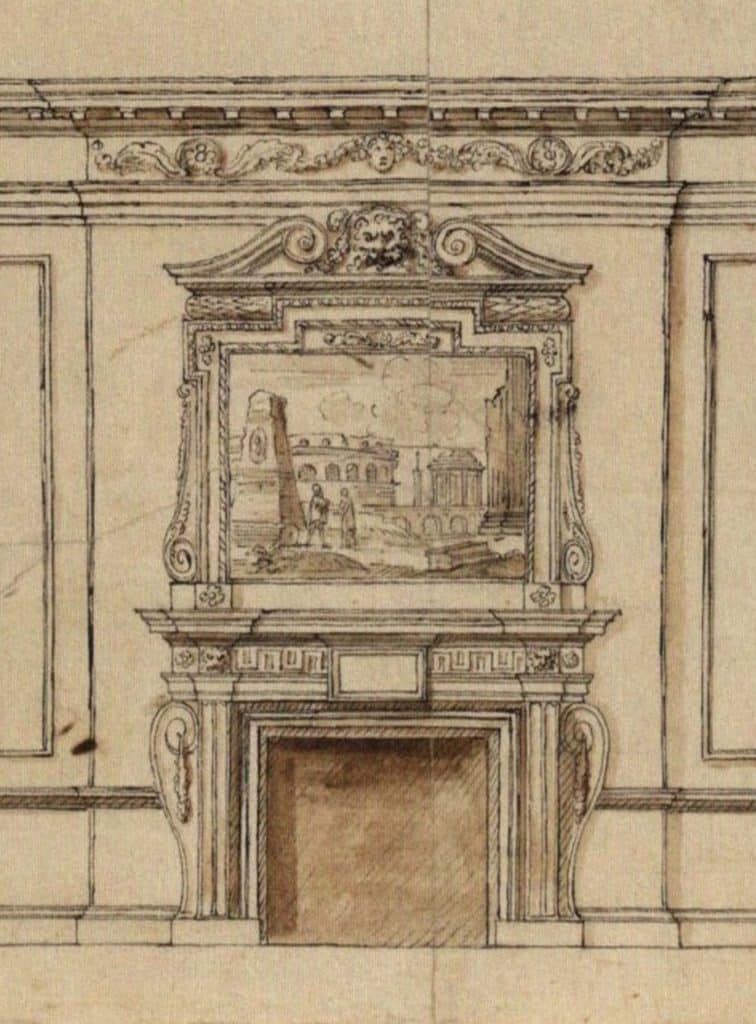

George II Palladian Fireplace Mantel, 1740s ($145,792)

This handsome George II fireplace mantel, crisply carved of white statuary marble, is “everything one would look for in an English fireplace of the period — very much in the style of Inigo Jones and William Kent, the grandees of eighteenth-century Palladianism,” says Wilfred Lewis, of the London gallery Jamb Ltd.

From the gargantuan size — more than 6 feet tall and 11 feet wide — and stellar quality of the material, it’s evident that the 1740s piece was made for the principal room of an important house.

The carving is spare above, with a plain inset frieze and simple egg-and-dart molding lining the shelf that breaks forward above the jambs, and more decorative below, with double scrolled consoles and hanging drops of acorns and oak leaves. “It’s the perfect sought-after balance of austerity and grandeur,” Lewis says.

Kay Bojesen Teak Monkey Toy, 1950s ($5,909)

Kay Bojesen’s mid-century modern monkey is a charmer, to be sure, and one of the most coveted pieces by the Danish silversmith and wooden-toy designer. Bojesen created, among other things, the Grand Prix silver service, known as Denmark’s national cutlery and found in Danish embassies worldwide, but it’s his wooden creatures — which also include plump birds, a yawning hippo and a painted zebra — that are most beloved.

With an expressive face and movable hook-like limbs that allow it to dangle playfully in any number of places around the house, the teak monkey “was a great hit when it was first introduced, in 1951, and it’s one of the great Danish design classics now,” says Alexander Nordling, of Stockholm’s Nordlings antique gallery. “It’s whimsical and beautiful at the same time.”

Exhibited at London’s Victoria and Albert museum in the 1950s, it became an instant icon.

The 12-inch version is the largest of four and the hardest to come by, Nordling says. “They were produced in very limited numbers compared with the smaller monkeys. It’s the large size that makes it so rare and sought after.”