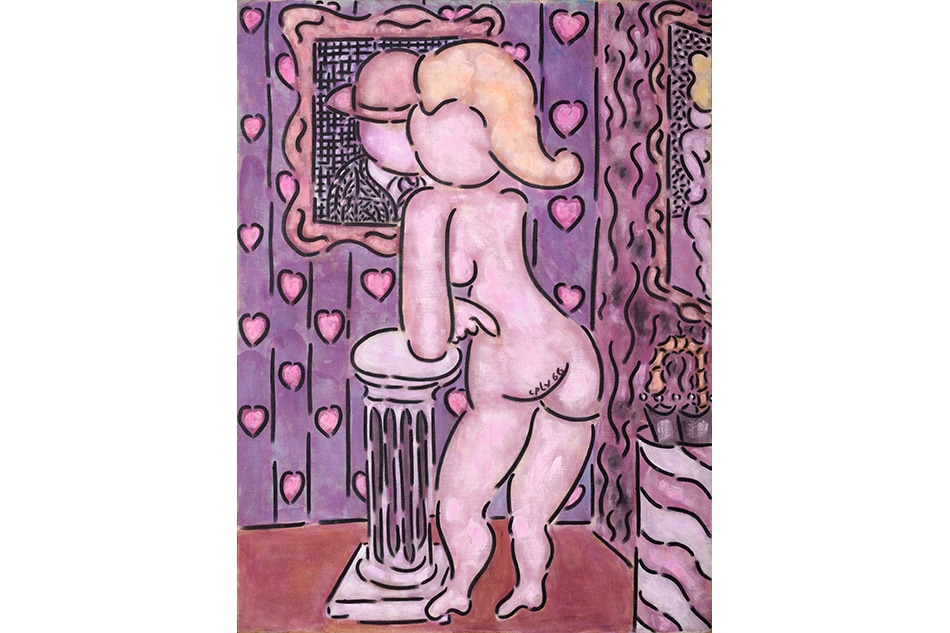

February 20, 2017A new show at Paul Kasmin Gallery, in New York, pays homage to 20th-century painter William N. Copley‘s obsession with the female form, which he rendered in Pop meets Surrealist style. Above, the artist works in his studio in 1965 (photo courtesy of the Frank J. Thomas Archives). Top: Conçue, 1982 (images, © 2016 Estate of William N. Copley / Copley LLC / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York).

What other subjects are there besides sex?” the late American painter William N. Copley once mused. One of the 20th century’s most entertaining iconoclasts, the self-taught, independently wealthy artist, dealer, collector, patron, philanthropist, writer, publisher and anti-establishment man about town certainly wasn’t the only artist (or human) to share Freud’s fascination with man’s primordial desires. But he was one of the few to articulate his fixation so openly and enthusiastically in art, as we see in “William N. Copley: Women,” a small retrospective at New York’s Paul Kasmin Gallery through March 25.

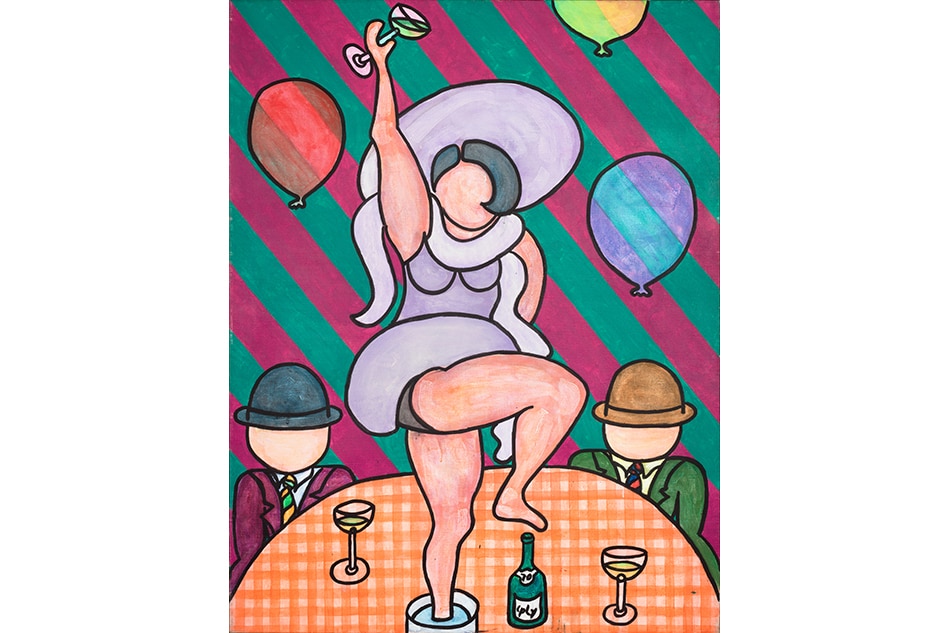

Female nudes or scantily clad women abounded in Copley’s work from the late 1940s through 1996, when he died at the age of 77. Often they are accompanied by his skirt-chasing alter ego, CPLY, a faceless man in a bowler hat and tweed suit. But what we see here is that the artist, who married six times and had an obvious fascination with adultery and prostitution, didn’t portray a woman’s body as a typical vessel of pleasure or paradigm of beauty but rather as a beloved and powerful psychological force. Saucy but never sleazy, more burlesque than debased, these canvases are a vibrant stage on which the libertine Copley cheerily played out his visions of Eros and excess. He had no tolerance for sexual taboos, and even the most explicit images on view here, from his “X-Rated” series of scenes from pornographic magazines the artist sourced in seedy 42nd street emporiums, seem less about the dark side of desire than about the fun and joy representing women brought him — sort of like the pleasure a truck-obsessed four-year-old pours into a drawing of a fire engine. “I don’t think my work is dirty. But I think it’s erotic,” he told an interviewer in 1968. “Eroticism and humor have to do with the sweetness of life.”

Battle of the Sexes No. 2, 1974, holds pride of place at one end of the Paul Kasmin show.

Under the Stars (Hommage à Picabia), 1994

His self-taught style — flat, colorful, cartoonish and full of energizing marks and patterning — is an unusual brew of offbeat Americana, Surrealism and Pop. That mix has always made him hard to categorize, situating him somewhat outside the mainstream, particularly at a time when abstraction, minimalism and conceptual art were more fashionable. That said, he was a true insider in some of the most influential art circles of the 20th century. Walter Hopps, the founder of Houston’s Menil Collection, called him the link between Surrealism and Pop and likened him to Charlie Chaplin and Buster Keaton, while Marcia Tucker, the bravely experimental founder of New York’s New Museum of Contemporary Art, showed some of his wildest work in the ’70s. Ed Ruscha and Carroll Dunham are among the numerous artists who collect his work, and he was close friends with a slew of boldface art-world names, from Marcel Duchamp, whose obit he wrote for the New York Times, to Andy Warhol, who made a silkscreen portrait of one of his wives and wanted to stage a play about his life, which was indeed a story worth telling.

Orphaned as an infant and then adopted by a very affluent couple from Illinois — a chance happening that critics connect with his love of the absurd and get-it-while-you-can attitude — Copley was raised in Southern California and educated aft Andover and Yale, from which he was drafted before receiving his degree to serve in World War II. He returned to Southern California after the war and on a whim opened a small gallery in Los Angeles with his brother-in-law, who had introduced him to Surrealism. They hunted down L.A. denizen Man Ray, who led them to Duchamp and the influential dealer Alexander Iolas. Iolas, in turn, connected them with René Magritte and Max Ernst, among other Surrealists. To convince these artists to show at his gallery, the extravagant Copley promised considerable guarantees, and when their works went unsold, he bought them up, forming one of the best collections of Surrealism in the States.

Jane, 1966

With Man Ray, he eventually moved to Paris and sunk comfortably into the Surrealist scene, painting, partying and sharpening his biting political humor. In 1962, he relocated to New York, hooking up with like-minded iconoclastic Pop artists and continuing to paint for the next few decades.

Always busy with something, he was bled dry by some of his more elaborate projects. In 1954, he created a foundation to provide grants to artists, and in 1968, he launched S.M.S (Shit Must Stop), a short-lived magazine that came with artists editions and served as an attempt to subvert the art market machine and publishing system. In need of money in 1979, he sold his art collection at Sotheby Parke Bernet for $6.7 million. Many of his Surrealist gems were purchased by Dominique de Menil and now reside in the Menil Collection, which, with the Prada Foundation, co-organized the first-ever major Copley retrospective last year. He died of complications from a stroke in 1996 in Sugarloaf Key, Florida, where he had lived since 1991.

“Understandably, there’s always a lot of focus on his personal story,” says Nick Olney, who organized the show at the Kasmin gallery, which has represented the late artist’s estate since 2009. Olney hopes this exhibition will help viewers see “the complexity of Copley’s paintings.” What unites many of these images of women — from dancing blondes, curvy and faceless (he didn’t like drawing faces), to empowered ladies of the night (identified, in part, by the inclusion of a bidet) — is Copley’s lively all-over patterning. “Think of Henri Matisse,” says Olney. Fernand Léger‘s graphic forms also come to mind, as do Thomas Hart Benton’s woozy, flowing forms and American heartland flavor. And of course, there are the bowler hats and umbrellas of Magritte, as well as some seamless Surrealist weaving of reality and fantasy. Sometimes he even added real lace and bits of lingerie to the surface of his paintings, disrupting the two-dimensional picture in a way that still feels peculiarly radical. It’s a heady, quirky mix with a lot to look at.

Some might find it hard to see past Copley’s casual bon vivant virility, but buried in much of his work is some trenchant cultural criticism. He mocked the pomp and circumstance of American patriotism, for instance, and pushed for a gentler understanding of prostitution. His “Tomb of the Unknown Whore” series (1965–83) posits the “unknown whore” as a war hero. As the artist, who saw battle during World War II, is quoted as saying in the catalogue for the recent retrospective: “The wars make bachelors out of everybody, and they lose their identity. And these girls are the only people that give them a little bit of their identity back…. War and prostitution are definitely the same. And these girls are probably a little more honest than the people who make war.”