November 22, 2020Tucked away in Paris’s second arrondissement, in a chic former textile district now buzzing with tech start-ups and design studios and punctuated by charming covered passages, is the eponymous workshop and showroom launched three years ago by Xavier Lavergne.

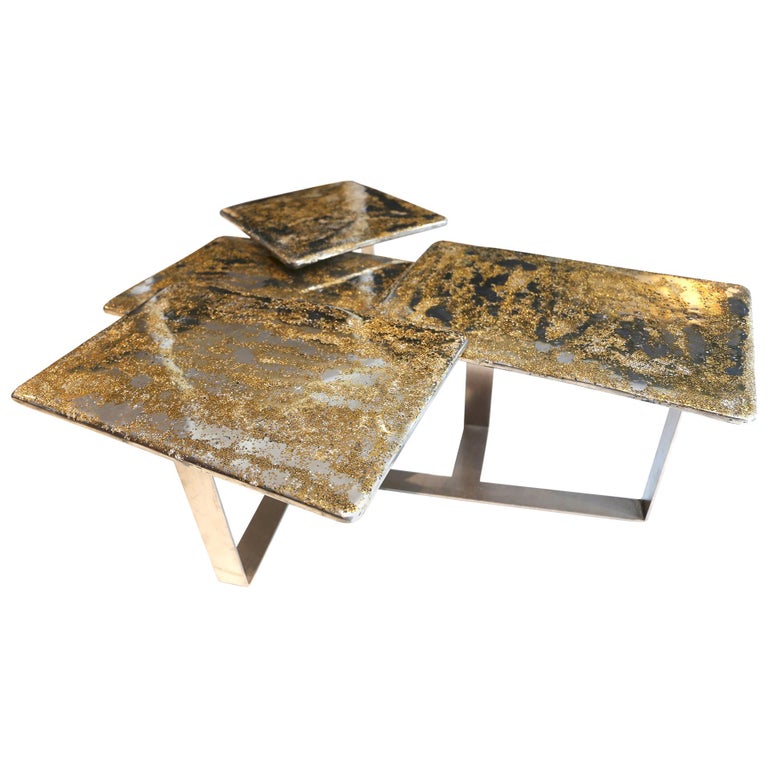

The space is situated between the Paris Stock Exchange and the Grand Boulevards, within walking distance of the Louvre. Displayed inside are the architect and designer’s distinctive, one-of-a-kind tables and countertops, fashioned from cast pewter, Murano glass and metal casting grains.

The now 55-year-old Frenchman earned his architecture license in 1995 and opened his own firm in 1998. He spent the next two decades working on prestigious architectural projects. These included public structures, like the European Commission headquarters, in Brussels, on which he collaborated with Jean Nouvel, and the French Pavilion in Osaka; as well as commercial and residential buildings, most notably a number of luxury townhouses in the posh suburb of Neuilly-sur-Seine, west of Paris. But his most prominent undertaking during this period was helming a large-scale construction and renovation at the Château de Versailles from 2010 to 2017.

While working at Versailles, Lavergne derived great satisfaction from collaborating with master artisans — roofers, carpenters, stonemasons, glassmakers, glaziers, gilders. This, coupled with his frustration with the French government’s strict guidelines for working on historic landmarks, led him to question his career.

“I yearned to follow a different path, to think outside the box, so I decided to pursue my childhood dream of creating unique pieces of furniture,” he explains. “I began to experiment, crafting them myself, like an alchemist, in a meticulous process of testing and researching, inventing my own ‘tools’ — not just objects but also gestures and ideas. My goal was to begin imagining new materials and designs that could play a role in building a sort of contemporary Versailles.”

Since then, Lavergne has developed several lines of furniture. His tabletops, coffee tables, side tables and consoles are made of melted pewter and resin and embedded with bronze casting grains or bits of Murano glass using techniques he has been exploring since the early 2000s.

Drawing inspiration from alchemy, hybrid life forms and morphogenesis (the biological process that causes organisms to develop a specific form), Lavergne’s creations suggest the splendor and mystery of the cosmos.

His collections bear names like Star Dust, Cracks, Bio-Stars, Scales, Galaxy, Meteors. Some of the opulent and lustrous pieces call to mind celestial bodies or extraterrestrial skies; others suggest more-earthly models, such as crocodile skins, insects, fossils, branches, puddles or seashells.

Lavergne loves the interplay of shadow and light in the table surfaces, but he wants to attain something “higher,” something metaphorical and poetic. “In addition to making something functional and beautiful,” he explains, “I want to go further, to give meaning, to address the mind as well as the eye.”

Lavergne’s conversation is peppered with such lyrical observations. He casually throws out references to such disparate and heady topics as Bachelard’s theory of material imagination, phenomenology, gastronomy, the transmutation of base metals, the immersive environments of kinetic artist Jesús Rafael Soto and James Turrell and French artist Hubert Duprat’s bejeweled caddisfly larvae.

He even reflects on the very nature of furniture: “What is a table? It’s so much more than a flat surface on a base,” he notes. “The term roundtable refers to a conference, a discussion, a way of exploring, clarifying, questioning, a way of opening one’s mind and reimagining the world.

“Picture the Arthurian myths about the king and his knights gathered around the Round Table,” he continues, “where everyone is equal, no sense of hierarchy — it’s an image of utopia.” This vision informs the vast selection of circular side and coffee tables he creates.

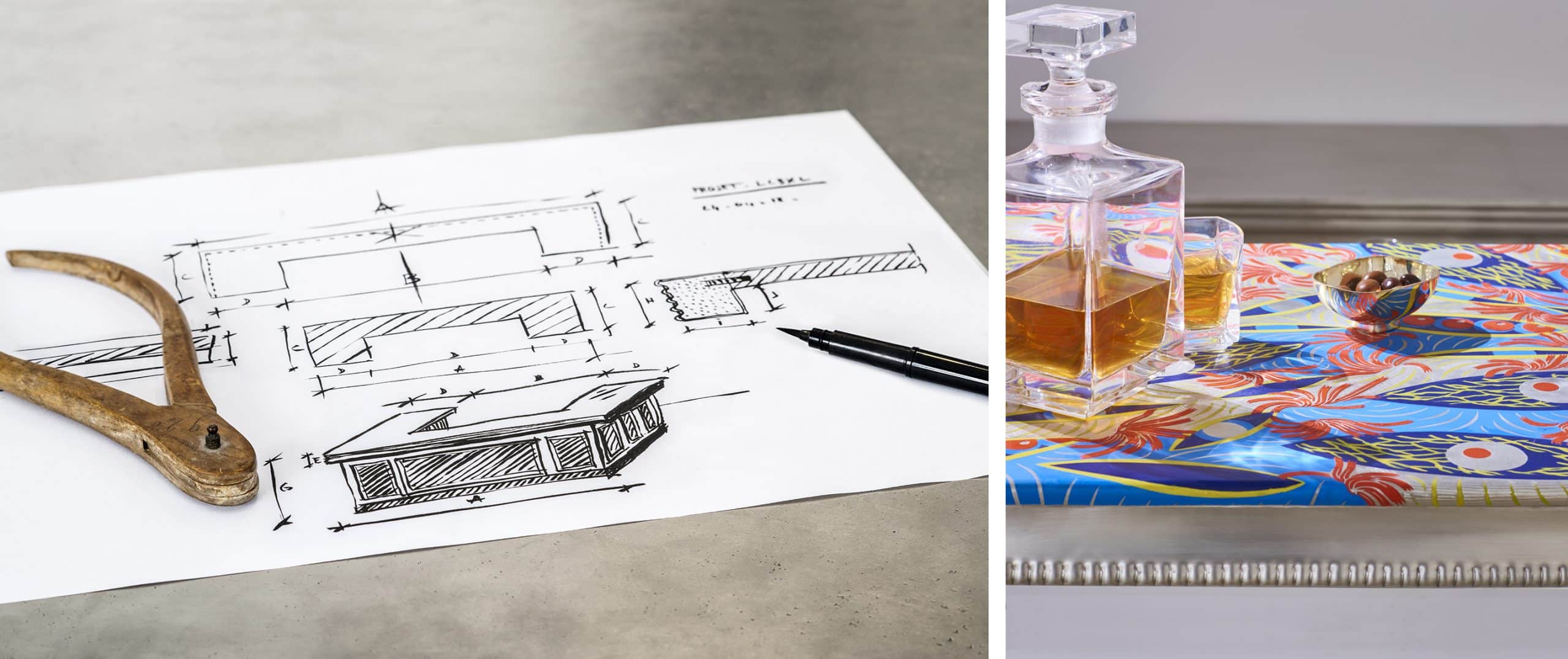

In the far corner of his showroom, a winding staircase leads to a downstairs workshop, an intimate laboratory where he tests mixing, heating and cooling techniques. It looks like a small-scale state-of-the-art kitchen for molecular gastronomy, with a bar, sink, stove, gadgets and vessels, ladles and measuring instruments and a central island cluttered with assorted containers of brightly colored caviar-like beads in glass, copper, bronze, aluminum and brass.

His main ingredient is the purest cast pewter — the bluish-gray alloy used in past centuries for serviceware (chargers, dishes, plates) or spoons and ecclesiastical flagons.

“In fact, it’s the fourth precious metal, after silver,” he says. “It’s incredibly malleable. So, by tweaking pressure, heat or humidity, you can use it to produce powerfully expressive forms. In its different states, it can be used as sheet metal, cast, bent, hammered, heated or molten. It can be frozen solid and combined with glass, minerals or other metals.”

In collaboration with a master metalsmith in the Pays de la Loire region, Lavergne has devised recipes for combining pewter with resin and imbuing the result with flecks of light by means of glass beads and casting grains.

Each of his creations is unique — he describes them as “alive.” Lavergne says, “The alchemy is imperfect, so the result is often unexpected, never reproducible.” They are all stamped with the Xavier Lavergne Ateliers logo and accompanied by a certificate of authenticity.

The pieces can also be customized, from the shape and dimensions of the tabletop to the height, width and material of the legs (crystal resin, brass, metal). A client in northern France, for instance, recently commissioned a Scales dining table with a wide metal base.

Upstairs from the showroom is a third space, devoted to Le Comptoir, a separate brand dedicated to bar counters for bistros, cafés, wine bars and restaurants.

“Bar counters bear the silent traces of lovers’ illicit rendezvous or good-byes,” he says, “of comings and goings, of barroom camaraderie or strangers passing through, of the pounding of beer mugs, the tapping of coins to get the barkeep’s attention, the dent of a cufflink or the rapping of a hard-boiled egg.”

With Le Comptoir, Lavergne has updated the traditional French bar counter, using wood covered in a thick sheet of pewter with custom moldings, either classic or contemporary.

He is currently collaborating with artists and engravers to bring the form into the 21st century with bold motifs inspired by video games, animated films, street art, comic books and tattoo art — one-of-a-kind pieces he calls “the antiques of the future.”

Lavergne is also expanding his experiments from “working dry” to “working wet”: combining glass and metals with walnut and moist clay, moving from the cosmos back to earth.

Meanwhile, he continues his architecture work, even winning recognition this past summer for his contribution to French culture by being named a Knight of the Order of Arts and Letters. And, inspired by the Bauhaus model of a total architecture, he is applying the techniques used in his innovative furniture to create walls, rooms and facades.

His ultimate goal is to design a single, seamless, harmonious space that embraces furniture, doorknobs, light fixtures, dinnerware and carpets — à la Frank Lloyd Wright and not unlike Richard Wagner’s mid-19th-century concept of Gesamtkunstwerk, or total work of art.

“I am incredibly excited about continuing on this journey,” Lavergne says, “always dreaming up new materials, new designs, new ideas that help me to imagine the Versailles of tomorrow.”