July 3, 2017Yossi Milo in his new 10th Avenue space (portrait by Matthew Brandt).

When Yossi Milo made his debut as a gallerist, in the late 1990s, in New York City’s Chelsea neighborhood, he lacked the usual backing and connections and knew little about art dealing or collecting; he was simply driven by a love of art. Born and raised in a tiny town north of Tel Aviv, he’d developed his passion as a child while attending a boarding school in Israel located next to the legendary Ein Hod Artists’ Village, founded by Dadaist Marcel Janco.

After his military service, Milo traveled extensively, landing in New York in 1988 and never leaving. Upon graduating with a degree in psychology from Baruch College in 1998, he opened a gallery with a partner in a walk-up space over a garage on West 24th Street, relaunching it in 2000 under his own name and dedicating it to photography. “Nothing about it was pretentious,” Milo says. “It was just about pictures. I took great care with every single detail of each presentation, and people noticed.”

He struck a nerve with his first show: black-and-white pictures of big-eyed, creepy-looking children in surreal settings by Simen Johan, a Norwegian-born photographer whom he’d spotted in a student exhibition at the Alternative Museum. “Simen was one of the first people to get a lot of attention for creating digitally manipulated photographs but producing them as traditional silver gelatin prints,” Milo says. “The images were really disturbing, and people liked them.” The gallery was off and running.

Today, Milo is one of New York’s preeminent photography dealers, known for championing not only Johan but also Germany’s Loretta Lux, similarly renowned for otherworldly portraits of children; the South African documentarian Pieter Hugo; the train-hopping lensman Mike Brodie, aka the Polaroid Kidd; and the process-based work of Matthew Brandt, Meghann Riepenhoff, Alison Rossiter and Marco Breuer.

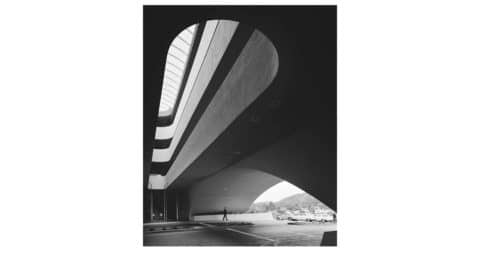

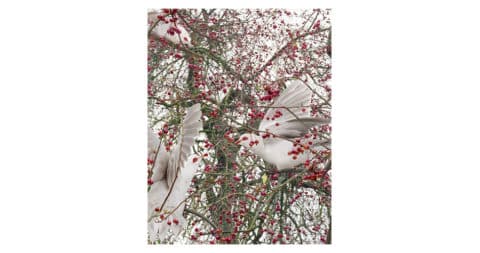

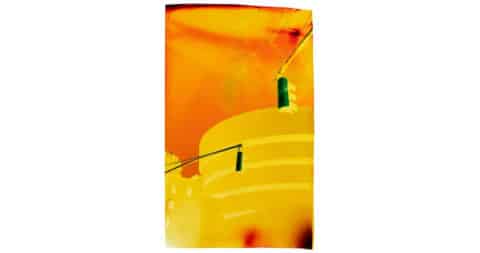

Now housed in a more lavish split-level 10th Avenue space, the gallery is currently showing work by Ezra Stoller, the great photographer of modernist architecture, for whose estate Milo is the exclusive representative. Called “Ezra Stoller Photographs Frank Lloyd Wright Architecture,” it’s timed to coincide with Wright’s 150th birthday and paired with the more conceptually minded show “Tree…,” which presents portraits by Korean photographer Myoung Ho Lee of trees standing like billboards in grassy fields. These come on the heels of an exhibition of photos by Mark Ruwedel, famed for his pictures of American deserts and the American West. That show included selections from Ruwedel’s 2014 book Pictures of Hell, depicting sites named for hell or the devil, and his 2014 “Opportunities Realized” series, which revisits sites depicted in Ed Ruscha‘s 1970 artist’s book Real Estate Opportunities, which documents tracts of land for sale throughout Los Angeles County.

For Twelve LPs, 2009–11, artist Mark Ruwedel captured heat-warped records littering a desert landscape, intending them as ruined versions of the pristine discs in Ed Ruscha’s book Records.

Along with running a full exhibition program and securing museum shows and major book publications for his artists around the world, Milo participates in several fairs, including New York’s Armory Show, Paris Photo, AIPAD and San Francisco Fog Art + Design. He prides himself on his jewel-box-like installations for these events. At the Armory this year, he presented primarily all-black process-based work by Brandt, Rossiter and Breuer, among others; for the ADAA Art Show, he created an installation of pieces by Breuer, who contributed colorful camera-less, free-form abstractions, and the British photographer Clare Strand, who offered black-and-white staged Weegee-esque pictures and a readymade sculpture. “I look at it as advertising,” Milo says. “When you have fifty to sixty thousand people passing by, it’s important to have a beautiful show. It’s also exciting to put together a booth that contextualizes photography within a contemporary art environment.”

On a recent afternoon, Milo talked with Introspective about what excites him, how he advises collectors and what he’s learned during his 17 years in business.

What’s the essential quality that attracts you to a photographer?

My tastes haven’t changed, they’ve just broadened. When the gallery began, I was drawn to photographers who displayed great craftsmanship. I mostly showed photographers who made large-format darkroom prints. And I have always been attracted to impactful representational imagery. However, over time, I became drawn to process-based work.

The first photographer who really expanded my vision that way was Alison Rossiter, who uses expired vintage silver gelatin paper to make stunning black-and-white abstract photographs without the aid of a camera. I also feel a deep connection with the work of Marco Breuer, who cuts, scrapes and even burns exposed and processed color photo paper to make the most transformative and genre-blurring art imaginable. Many of the artists I represent use photographic processes to bridge the gap between representation and abstraction, like Matthew Brandt, who recently documented bridges in Flint, Michigan, and developed the prints using the city’s contaminated water.

How did you come to represent the estate of Ezra Stoller?

I have always been enamored of architecture, especially buildings from the modernist period. After all, Tel Aviv has the highest concentration of Bauhaus architecture in the world. The photographs of designs by Philip Johnson, Eero Saarinen and Skidmore, Owings and Merrill that I studied in books were often by Ezra Stoller, although I did not know it at the time. In the later years of Stoller’s life, when prints of his iconic photographs were produced, I was already in love with them. Meeting his extraordinary daughter, Erica, and sharing our passion for the work forged our friendship and working relationship.

At the gallery through August 25, we are presenting an exhibition of Stoller’s photographs of Frank Lloyd Wright buildings, in honor of the 150th anniversary of the architect’s birth. Included are images of the Guggenheim Museum; Fallingwater; the Johnson Wax Tower, in Racine, Wisconsin; and Taliesin, Wright’s home in Scottsdale, Arizona.

In tandem with the Stoller show, we are pleased to present Korean artist Myoung Ho Lee’s second exhibition at the gallery — his first U.S. solo show since 2009. The artist’s “portraits” of trees — created with tremendous effort using a team of people and heavy cranes to hoist an enormous backdrop behind a tree as it grows in the landscape — provide a surreal twist to traditional landscape photography.

How does someone like Mark Ruwedel fit into your program?

He is among the gallery’s few classic black-and-white photographers. Think Robert Adams, Lewis Baltz or Frank Gohlke. For more than thirty years, he has produced bodies of work that reinforce and build on each other, bound by strong conceptual threads. He has followed the path of the American railways, abandoned after the collapse of industry. He has documented ruined homes, bomb craters formed by military tests and the remains of decades-old earthworks. He is also a master printer, making pristine gelatin silver prints. And he often presents groups of images as a typology, in the style of Bernd and Hilla Becher.

Is there a commonality uniting the works you show, from the children to Ruwedel to pure abstraction?

To me, it is always the work’s immediate visual impact and psychological complexity. Usually, it is topical and speaks to the essence of the medium. But art doesn’t always need to be challenging. It can also just be something beautiful, because beauty is part of life, and collectors have to live with the objects they purchase.

You seem to choose artists for your gallery based on your gut reaction to their work, rather than worrying about whether it will be commercial. Are the two related?

I run the gallery with the same advice I give collectors. Trust your instincts. I base a lot on my first reaction. If I have a powerful experience with a work of art, I believe many other people will, too.

Was it a drawback to start out with no connections, knowing nothing about the gallery world?

I think of it as an advantage. I saw the industry with fresh eyes and made my own path without using a standard approach.

What’s the first important thing you learned about being a dealer?

How hard it is: You are constantly facing tons of challenges. And never skimp on framing! It sounds funny, but it’s true. Presentation plays an enormous role in conveying art’s importance.

What advice would you give a new collector?

Open a dialogue. Ask questions of the gallerist. Many dealers love talking about the work to people who are engaged. If, after learning more and seeing more, you find yourself responding to the work, start collecting. It’s enormously gratifying to be a part of an artist’s development and to be able to own markers in time across that artist’s life.

TALKING POINTS

Yossi Milo shares his thoughts on a few choice pieces